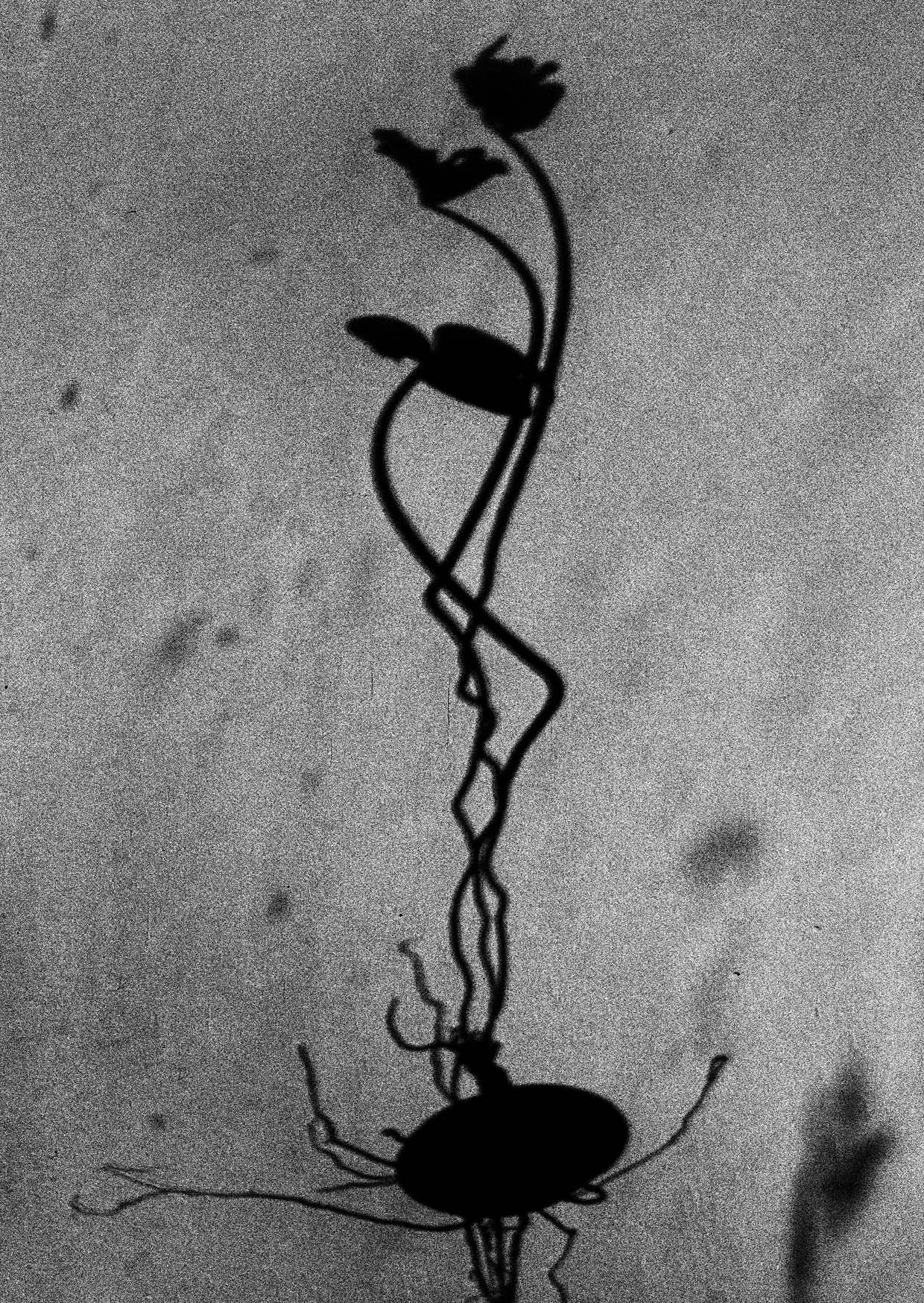

Wieke Willemsen,

‘Still life, Point Addis Beach,’ © 2024.

‘Still life, Point Addis Beach,’ © 2024.

Cyclamen / Poems After Baudelaire

Alix Chauvet

Tenement Press #20

978-1-917304-09-2

149pp

£17.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 5th September 2025

Chauvet’s debut, a suite of unfaithful translations /

transversions of works drawn from Baudelaire’s

Les Fleurs du mal / Flowers of Evil : a bunch of

flowers in decay, pressed and frayed, ‘a flock of

pockmarked words.’

READ AN EXCERPT ℅ TENEMENT’S REHEARSAL

Alix Chauvet

Tenement Press #20

978-1-917304-09-2

149pp

£17.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 5th September 2025

Chauvet’s debut, a suite of unfaithful translations /

transversions of works drawn from Baudelaire’s

Les Fleurs du mal / Flowers of Evil : a bunch of

flowers in decay, pressed and frayed, ‘a flock of

pockmarked words.’

READ AN EXCERPT ℅ TENEMENT’S REHEARSAL

A Translator’s Note Ominous Foils

I have had a gullible and complicit admiration for Baudelaire since the day I was introduced to him; namely, the day I learned the word ‘albatross.’ I had been asked to memorise a poem of the same name and illustrate it in a school notebook. I drew the bird with a strong line in the centre of a blank page turned blue, its giant wings spread out, as I had also just been told that they prevented it from walking. Making the ‘prince of clouds’ mine through my strokes enmeshed me to the poet from the age of seven on.

This conviction—both my understanding Baudelaire and my being seen by him—followed me into my adolescence when I read the entirety of Les Fleurs du mal / The Flowers of Evil for the first time. I felt attracted to the violence of the collection; a ferocity that resonated with the intensity of those years of inner turmoil. Despite the recurrent obscenities against women, I sided with the ‘reader’—with the ‘brother,’ the ‘fellow man’—to whom the work is addressed. I was manifestly suffering from a literary Stockholm syndrome, forgiving the author for every one of his crudities, recognising each element of beauty within them, and padding them out with talismanic thinking to undermine the wound.

Translating Baudelaire’s oeuvre responds to a need to explore this connivance. I want to reach the hanging point at which I simultaneously encounter familiarity and alienation by immersing myself in his poems. I share Lisa Robertson’s intuition that the substance of Les Fleurs du mal is feminine—a ‘bildungsroman in the feminine’—in that by reading its thorny passages and filling them with my own voice, I experience a disarming appropriation. I envision my rewritings as a practice of feminine freedom, in which I hold the transgressive foil of language instead of enduring its blade in silence.

![]()

![]() Left—Chauvet, 'Stems from a shadow,' © 2024.

Left—Chauvet, 'Stems from a shadow,' © 2024.

Right—Chauvet, photographed by Daria Lou Nakov, © 2024.

To begin with the translation of the ‘Spleen’ series, amongst all others, is fortuitous. Their echo of the misty views of an autumnal Amsterdam last October certainly prompted such a step. In hindsight, the elusive nature of the Anglicism ‘spleen’ gives further credence to this occurence. The term bears new meanings in its Baudelairian usage, so that translating it back into English involves a shift in signification.

Like a rhizome, the definition of the blood-filtering organ is reoriented towards apathy. Deep melancholy. Disgust with life. Such a displacement reveals both the kinship between languages and the transformations at play in the translation process, which has been part of my method. The latter is metonymic, introspective and intuitive, for it draws from its source more than it has, through contingent associations mixing intra- and intersemiotic features. Following Baudelaire’s lines one by one, I cast homologous sentences onto the page as with a pendulum. This throwness produces resonances and dissonances that fog up the original text as much as they reveal it.

These cryptic correspondences to which I alone hold the key put the filiation between the source material and its translation to the test. I summon belief from the reader by playing with the nebulous open-endedness of language. Multiplying hermetic symbols, I jeopardise access to meaning, deliberately resisting narration in favour of collision and event as I write. My intention is not to be understood nor to comprehend, but to transpose the emotions and physical sensations aroused while reading Baudelaire’s verses.

In this regard, my method is embodied. Corseted in twelve syllable lines, my sentences mimic the Alexandrian form of the original poems, using metrics as a container, like a womb. Filled with aggression, sadness and derision, they contrast the inherent theme of death with that of birth, offering a feminist counterweight to their source, allowing me to turn my submissive collusion into an assertive sisterhood.

This conviction—both my understanding Baudelaire and my being seen by him—followed me into my adolescence when I read the entirety of Les Fleurs du mal / The Flowers of Evil for the first time. I felt attracted to the violence of the collection; a ferocity that resonated with the intensity of those years of inner turmoil. Despite the recurrent obscenities against women, I sided with the ‘reader’—with the ‘brother,’ the ‘fellow man’—to whom the work is addressed. I was manifestly suffering from a literary Stockholm syndrome, forgiving the author for every one of his crudities, recognising each element of beauty within them, and padding them out with talismanic thinking to undermine the wound.

Translating Baudelaire’s oeuvre responds to a need to explore this connivance. I want to reach the hanging point at which I simultaneously encounter familiarity and alienation by immersing myself in his poems. I share Lisa Robertson’s intuition that the substance of Les Fleurs du mal is feminine—a ‘bildungsroman in the feminine’—in that by reading its thorny passages and filling them with my own voice, I experience a disarming appropriation. I envision my rewritings as a practice of feminine freedom, in which I hold the transgressive foil of language instead of enduring its blade in silence.

Right—Chauvet, photographed by Daria Lou Nakov, © 2024.

To begin with the translation of the ‘Spleen’ series, amongst all others, is fortuitous. Their echo of the misty views of an autumnal Amsterdam last October certainly prompted such a step. In hindsight, the elusive nature of the Anglicism ‘spleen’ gives further credence to this occurence. The term bears new meanings in its Baudelairian usage, so that translating it back into English involves a shift in signification.

Like a rhizome, the definition of the blood-filtering organ is reoriented towards apathy. Deep melancholy. Disgust with life. Such a displacement reveals both the kinship between languages and the transformations at play in the translation process, which has been part of my method. The latter is metonymic, introspective and intuitive, for it draws from its source more than it has, through contingent associations mixing intra- and intersemiotic features. Following Baudelaire’s lines one by one, I cast homologous sentences onto the page as with a pendulum. This throwness produces resonances and dissonances that fog up the original text as much as they reveal it.

These cryptic correspondences to which I alone hold the key put the filiation between the source material and its translation to the test. I summon belief from the reader by playing with the nebulous open-endedness of language. Multiplying hermetic symbols, I jeopardise access to meaning, deliberately resisting narration in favour of collision and event as I write. My intention is not to be understood nor to comprehend, but to transpose the emotions and physical sensations aroused while reading Baudelaire’s verses.

In this regard, my method is embodied. Corseted in twelve syllable lines, my sentences mimic the Alexandrian form of the original poems, using metrics as a container, like a womb. Filled with aggression, sadness and derision, they contrast the inherent theme of death with that of birth, offering a feminist counterweight to their source, allowing me to turn my submissive collusion into an assertive sisterhood.

A. Chauvet

MMXXIV

For the attention of ‘brick & mortar’ bookshops,

order copies of Chauvet’s Cylamen via our distributor,

Asterism Books.

Chauvet, reading alongside Sharon Kivland /

Stichting Perdu, Amsterdam (19.12.25).

Stichting Perdu, Amsterdam (19.12.25).

Readings

18.30 / 03.10.25

Readings from Chauvet’s Cyclamen

Alix Chauvet

& Nadia de Vries

San Serriffe

Sint Annenstraat

Amsterdam

The Netherlands

See here.

17:30 / 31.08.25

Five Readers /

Alix Chauvet,

Cleo TSW,

David Grundy,

Gabriel Bristow TRUMPET SOLO!

Siyabonga Njica

Rietlanden Women’s Office

Oudeschans 35

Amsterdam

The Netherlands

See here.

Through these creative ‘translations’ of Charles Baudelaire, Alix Chauvet—artist, designer, poet—refuses fidelity in favour of flirtation: her ‘flowers of evil’ line Amsterdam’s canals, drink from the same rainclouds as Rachel Ruysch’s bewitching bouquets, sprout through peat, and are tended by a distinctly feminist and nomadic sensibility. Chauvet—akin to Olive Moore, Sean Bonney and Lisa Robertson—takes the nineteenth-century French decadent as a contemporary accomplice for aesthetic and linguistic misbehaviour. Walter Benjamin once wrote of Baudelaire that he is ‘der geheime Architekt der Moderne,’ and in Chauvet’s hands, those foundations are made porous, unbuilt into cast shadows, into ribbons, into veins streaming across the page. Accompanied by scans of the French poems and Chauvet’s shadow photography, what Cyclamen ultimately offers us is a regenerative rewilding of the English language: a wondrous terrain ringed by vines of unruly syntax and dotted with the fruit of words refusing domestication by any single tongue.

Mia You

Alix Chauvet’s take on Les Fleurs du mal is clever and delicious. Her poems upend the language of Baudelaire and channel it through a feminist lens, both critical and sensual—sharp and funny—I’ve never read anything like it.

Nadia de Vries

Alix Chauvet turns Baudelaire inside out, riffing off flavours, associations, sound resemblances, odd lines of thought and query, hints and orts in the source that ring true and screwy, and patches together strange surreal corporeal entities... Language events that estrange the dark sentences of the French poet, tracking potential triangulations, latencies in the precincts of the textual unconscious, pilfering lines to generate lines of inquiry and surmise and a new ‘estranged soma’ of radical translation-as-new body; new work that is feminist, contemporary, sprightly and alive with speculative energies; a Baudelaire exploded by Rimbaud, Dada, Stein.

Adam Piette

![]()

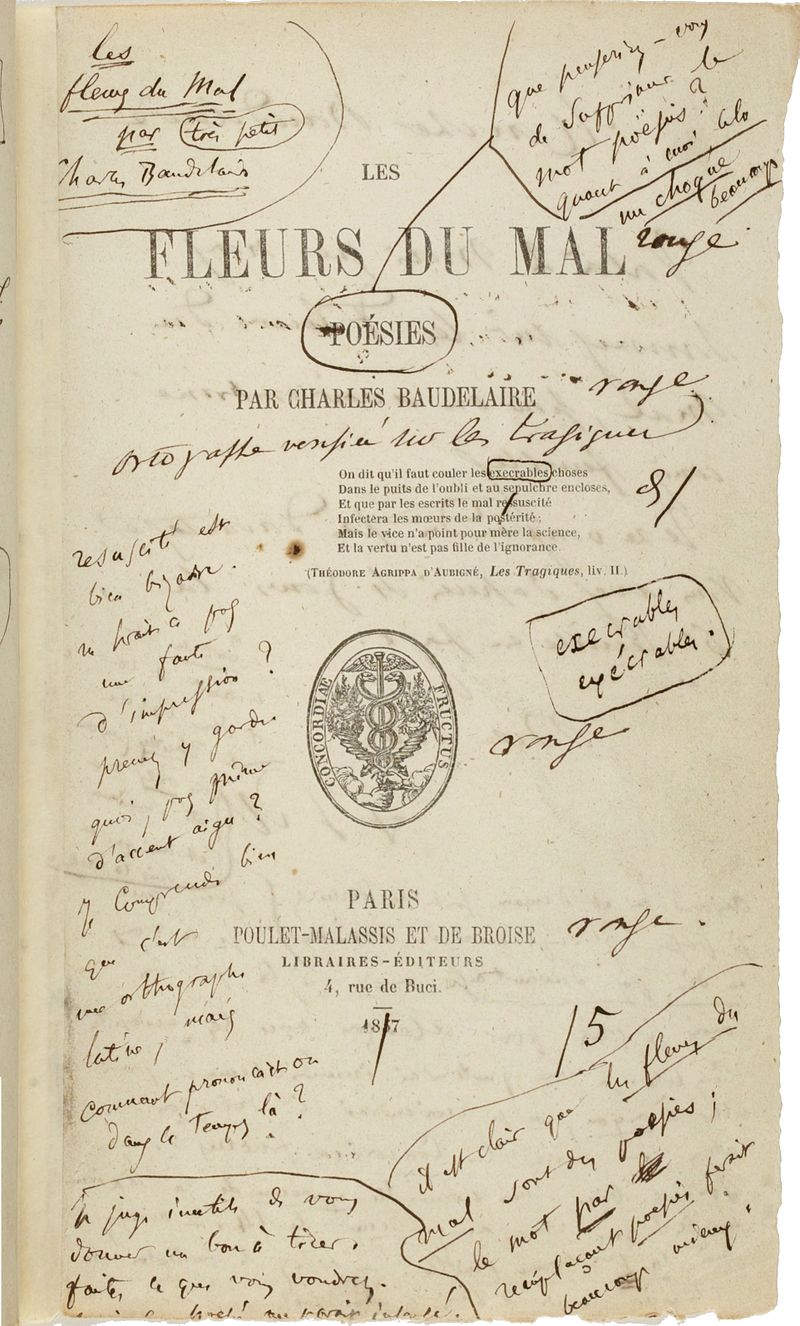

Baudelaire’s annotations to the frontispiece of

the 1857 Poulet-Malassis et de Broise edition

of Les Fleurs du mal / The Flowers of Evil,

℅ the Gallica Digital Library (ID: btv1b86108314/f23).

LUSTRE / After LXXVI. Spleen

J'ai plus de souvenirs que si j'avais mille ans.

My mind hangs like a chandelier.

Un gros meuble à tiroirs encombrés de bilans,

A toad-like squat armchair knocked up with verdant debts—

De vers, de billets doux, de procès, de romances,

verses and april rains earthworms, ravens and slugs—

Avec de lourds cheveux roulés dans des quittances,

with some horsehair curling in the midst of a lull,

Cache moins de secrets que mon triste cerveau.

lies less convincingly than my reclining skull.

C'est une pyramide, un immense caveau,

It’s a fancy hotel, a deep cemetery,

Qui contient plus de morts que la fosse commune.

that receives socialites on its sterile compost.

—Je suis un cimetière abhorré de la lune,

—I am an apricot that the tide has thrown up

Où comme des remords se traînent de longs vers

in its flesh, hushed taboos imitate the maggots

Qui s'acharnent toujours sur mes morts les plus chers.

assaulting ruthlessly the so-called cold-hearted.

Je suis un vieux boudoir plein de roses fanées,

I am grumpy-dopey trapped in a potpourri

Où gît tout un fouillis de modes surannées,

In which marbles collide amongst phoney bustles

Où les pastels plaintifs et les pâles Boucher

where falsified Degas and dolls made of rind

Seuls, respirent l'odeur d'un flacon débouché.

get drunk on petulant jasmine emanations.

Rien n'égale en longueur les boiteuses journées,

Nothing equals in pain the never-ending lacks

Quand sous les lourds flocons des neigeuses années

when under the deaf snows of countless alibis

L'ennui, fruit de la morne incuriosité

absence, the trace of the night train rendered invisible

Prend les proportions de l'immortalité.

echoes all the lost time, its wingspan you deny.

—Désormais tu n'es plus, ô matière vivante!

—Your injury’s no more, fleeting tendinitis!

Qu'un granit entouré d'une vague épouvante,

Than a crippled pretext serving as reposoir

Assoupi dans le fond d'un Sahara brumeux;

for your memory blown by a pale sirocco.

Un vieux sphinx ignoré du monde insoucieux,

A caterpillar hangs from the Corsican tree,

Oublié sur la carte, et dont l'humeur farouche

—its skeletal motif recalls the depths of things,

Ne chante qu'aux rayons du soleil qui se couche.

—the very point at which the moon sets with a blush.

Mia You

Alix Chauvet’s take on Les Fleurs du mal is clever and delicious. Her poems upend the language of Baudelaire and channel it through a feminist lens, both critical and sensual—sharp and funny—I’ve never read anything like it.

Nadia de Vries

Alix Chauvet turns Baudelaire inside out, riffing off flavours, associations, sound resemblances, odd lines of thought and query, hints and orts in the source that ring true and screwy, and patches together strange surreal corporeal entities... Language events that estrange the dark sentences of the French poet, tracking potential triangulations, latencies in the precincts of the textual unconscious, pilfering lines to generate lines of inquiry and surmise and a new ‘estranged soma’ of radical translation-as-new body; new work that is feminist, contemporary, sprightly and alive with speculative energies; a Baudelaire exploded by Rimbaud, Dada, Stein.

Adam Piette

Baudelaire’s annotations to the frontispiece of

the 1857 Poulet-Malassis et de Broise edition

of Les Fleurs du mal / The Flowers of Evil,

℅ the Gallica Digital Library (ID: btv1b86108314/f23).

LUSTRE / After LXXVI. Spleen

J'ai plus de souvenirs que si j'avais mille ans.

My mind hangs like a chandelier.

Un gros meuble à tiroirs encombrés de bilans,

A toad-like squat armchair knocked up with verdant debts—

De vers, de billets doux, de procès, de romances,

verses and april rains earthworms, ravens and slugs—

Avec de lourds cheveux roulés dans des quittances,

with some horsehair curling in the midst of a lull,

Cache moins de secrets que mon triste cerveau.

lies less convincingly than my reclining skull.

C'est une pyramide, un immense caveau,

It’s a fancy hotel, a deep cemetery,

Qui contient plus de morts que la fosse commune.

that receives socialites on its sterile compost.

—Je suis un cimetière abhorré de la lune,

—I am an apricot that the tide has thrown up

Où comme des remords se traînent de longs vers

in its flesh, hushed taboos imitate the maggots

Qui s'acharnent toujours sur mes morts les plus chers.

assaulting ruthlessly the so-called cold-hearted.

Je suis un vieux boudoir plein de roses fanées,

I am grumpy-dopey trapped in a potpourri

Où gît tout un fouillis de modes surannées,

In which marbles collide amongst phoney bustles

Où les pastels plaintifs et les pâles Boucher

where falsified Degas and dolls made of rind

Seuls, respirent l'odeur d'un flacon débouché.

get drunk on petulant jasmine emanations.

Rien n'égale en longueur les boiteuses journées,

Nothing equals in pain the never-ending lacks

Quand sous les lourds flocons des neigeuses années

when under the deaf snows of countless alibis

L'ennui, fruit de la morne incuriosité

absence, the trace of the night train rendered invisible

Prend les proportions de l'immortalité.

echoes all the lost time, its wingspan you deny.

—Désormais tu n'es plus, ô matière vivante!

—Your injury’s no more, fleeting tendinitis!

Qu'un granit entouré d'une vague épouvante,

Than a crippled pretext serving as reposoir

Assoupi dans le fond d'un Sahara brumeux;

for your memory blown by a pale sirocco.

Un vieux sphinx ignoré du monde insoucieux,

A caterpillar hangs from the Corsican tree,

Oublié sur la carte, et dont l'humeur farouche

—its skeletal motif recalls the depths of things,

Ne chante qu'aux rayons du soleil qui se couche.

—the very point at which the moon sets with a blush.

Alix Chauvet is a Swiss-French poet and graphic designer based in Amsterdam, taking pleasure in the possibilities of translation. She received her BA in graphic design from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam, 2020, and has since been working independently and in collaboration with contemporary artists. Investigating the relationship between language and body, her hybrid practice covers a wide range of visual and linguistic experiments—from artist’s book design to experimental translation. Her method is rooted in slowing down the creative process through the use of analogue and unprofitable techniques such as cut-outs, letterpress, linocut, handwriting and painting. Her poetic approach follows the same logic, prioritising English over her mother tongue as a way to relate to language with both critical detachment and a degree of identification. Her poems appeared in literary magazines such as Blackbox Manifold. Cyclamen is Chauvet's debut collection.