Gaza, the Old Town (circa 1862),

Albumen Print, ℅ the Library of Congress.

٤٨ كغم /

48kg.

Batool Abu Akleen

Translated from the Arabic by the poet,

with Graham Liddell, Wiam El-Tamami,

Cristina Viti & Yasmin Zaher

Tenement Press #19

978-1-917304-03-0

135pp

(eds.) Dominic J. Jaeckle

& Cristina Viti

£17.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 16th June 2025

One of the most viscerally affecting collections of poems I have ever read. Devastatingly precise and unforgettable images emerge from every line. The Arabic and the English sit side by side on the pages of this book but the effect is deeper than language, it meets the reader in the heart. I wept reading this brilliant, natural, gifted young poet and wished her subject was something other than this atrocity visited upon her and her people.

What is happening in Gaza is a genocide not a war, but not since Akhmatova have I read poetry that so potently reckons with the relationship between war and the body. They create a new category of literary grace out of the cataclysm. These are poems of fire and agony, bombing and starvation, but they are also poems of grace, cleverness, tenderness and yearning. A great international poet arrives with this collection, but it is also a landmark work of resistance. No human should have to write their poetry from inside death's dominion, but Batool Abu Akleen has done it and the result is truly astonishing.

Max Porter

Batool Abu Akleen writes sinuous, urgent, intimately provocative poems that we need. Etel Adnan’s work comes to mind in these poems’ frankness and fervour; and they’re happening today.

Eileen Myles

The poets of Palestine have become vital archivists. In 48Kgs Batool Abu Akleen not only provides brute testimony of the Genocide committed by Israel against her people, but by her inventiveness and surreality, by the barbed humour and bitter irony of her voice, and the tender revelation and humane wisdom of her work, she defiantly gives voice and futurity to Palestinian life. She writes that she waits for death, ‘like a mother expecting her newborn’ telling us ‘I will scream / I will feel his head coming out of my body.’ No one should have to write these incredible, haunting lines, but everyone should read them. This is an extraordinary book of poetry.

Jack Underwood

A debut collection from the Palestinian poet—Modern

Poetry in Translation’s ‘Poet in Residence,’ 2024—a

bilingual assembly of forty-eight poems in which each

work accounts for a single kilogram; a body’s mass; a

testament to a sieged city; a vivid and visceral

voicing of the personal and the public in the

midsts of unspeakable violence.

هكذا أطهو حزني / This is how I cook my grief

48kg.

Batool Abu Akleen

Translated from the Arabic by the poet,

with Graham Liddell, Wiam El-Tamami,

Cristina Viti & Yasmin Zaher

Tenement Press #19

978-1-917304-03-0

135pp

(eds.) Dominic J. Jaeckle

& Cristina Viti

£17.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 16th June 2025

One of the most viscerally affecting collections of poems I have ever read. Devastatingly precise and unforgettable images emerge from every line. The Arabic and the English sit side by side on the pages of this book but the effect is deeper than language, it meets the reader in the heart. I wept reading this brilliant, natural, gifted young poet and wished her subject was something other than this atrocity visited upon her and her people.

What is happening in Gaza is a genocide not a war, but not since Akhmatova have I read poetry that so potently reckons with the relationship between war and the body. They create a new category of literary grace out of the cataclysm. These are poems of fire and agony, bombing and starvation, but they are also poems of grace, cleverness, tenderness and yearning. A great international poet arrives with this collection, but it is also a landmark work of resistance. No human should have to write their poetry from inside death's dominion, but Batool Abu Akleen has done it and the result is truly astonishing.

Max Porter

Batool Abu Akleen writes sinuous, urgent, intimately provocative poems that we need. Etel Adnan’s work comes to mind in these poems’ frankness and fervour; and they’re happening today.

Eileen Myles

The poets of Palestine have become vital archivists. In 48Kgs Batool Abu Akleen not only provides brute testimony of the Genocide committed by Israel against her people, but by her inventiveness and surreality, by the barbed humour and bitter irony of her voice, and the tender revelation and humane wisdom of her work, she defiantly gives voice and futurity to Palestinian life. She writes that she waits for death, ‘like a mother expecting her newborn’ telling us ‘I will scream / I will feel his head coming out of my body.’ No one should have to write these incredible, haunting lines, but everyone should read them. This is an extraordinary book of poetry.

Jack Underwood

A debut collection from the Palestinian poet—Modern

Poetry in Translation’s ‘Poet in Residence,’ 2024—a

bilingual assembly of forty-eight poems in which each

work accounts for a single kilogram; a body’s mass; a

testament to a sieged city; a vivid and visceral

voicing of the personal and the public in the

midsts of unspeakable violence.

هكذا أطهو حزني / This is how I cook my grief

أقطف من الشارع قلوباً طازجةً

أختار أكثرها خيبةً

بيدٍ خفيفةٍ أسرق الدموع

.أعبئ رائحة الحزن في علب السردين الصدئة

نظرات الأمهات تلتصق بأعينهن بشدة

.فأخطفها برشاقةٍ لأني أشبه أطفالهن

في قدرٍ نحاسيٍ

أغلي كل مسروقاتي

أضيف لها دماً لم تشربه الأرض بعد

.ونشارةَ تابوتٍ كان باباً لبيته الجديد

أسكبُ الخليطَ في قلبي

فيصبح أسوداً

هكذا أطهو حزني

أختار أكثرها خيبةً

بيدٍ خفيفةٍ أسرق الدموع

.أعبئ رائحة الحزن في علب السردين الصدئة

نظرات الأمهات تلتصق بأعينهن بشدة

.فأخطفها برشاقةٍ لأني أشبه أطفالهن

في قدرٍ نحاسيٍ

أغلي كل مسروقاتي

أضيف لها دماً لم تشربه الأرض بعد

.ونشارةَ تابوتٍ كان باباً لبيته الجديد

أسكبُ الخليطَ في قلبي

فيصبح أسوداً

هكذا أطهو حزني

I pick fresh hearts from the street

the most defeated ones

with nimble fingers I steal the tears

I fill rusted sardine tins with the smell of sorrow.

Mothers’ glances cling tight to their eyes

but I snatch them easily, because I resemble their children.

In a copper pot

I boil what I’ve stolen

add the blood that hadn't been absorbed

& sawdust from a coffin meant as the door to a new home.

I pour the mixture into my heart

until it blackens.

This is how I cook my grief.

*

SEE HERE FOR SEA SHELLS

Sea Shells—published by Modern Poetry in Translation—is a digital pamphlet collating the works of nine emerging Gazan poets, selected and translated by Abu Akleen, edited by Cristina Viti, and including works by—

Wadah Abu Jami

Rawan Qwaider

Mojeeb Al Bayed

Asmaa Dwaima

Mariam Mohammed Al Khateeb

Heba Al-Agha

Tamer Khail

Yazeed Shaat

& Samar Al Guhssain

Sea Shells was published in tandem with the Tenement release of Abu Akleen’s 48Kg., 16.06.25, with thanks to Janani Ambikapathy and Ed Cottrell.

48Kg. Editor’s Note

I was introduced to the poetry of Batool Abu Akleen thanks to an Italian translation written by Aldo Nicosia for an anthology of women’s poetry and art dedicated to the memory of Etel Adnan. *

I was impressed with this young poet’s ability for close observation and empathy and by the immediacy and vividness of her language. In one instance, in a poem she wrote at the age of fifteen in 2020, she takes on the voice of a mother to describe daily life in a Palestinian refugee camp and the physical and psychic impact of the violence of borders on adults and children alike. Publication of the anthology, for which I wrote an English version of that poem, led to a series of events and exhibitions in which some of Batool’s paintings were also shown, and to the beginning of our correspondence and friendship. Thanks to her good command of English and to her perseverance and courage against the ongoing massacre of her people, we were able to co-translate a number of other poems.

Over the past few months, while going through a number of evacuations, continuing her studies via distance learning following the razing of her faculty in Gaza City, holding English classes for some of the children residing in the camp where she lives and honouring her commitments as translator in residence for Modern Poetry in Translation, Batool has worked to assemble her first collection and make English versions of her poems—most of them self-translated, except for a few made in collaboration with Graham Liddell, Wiam El-Tamami, Yasmin Zaher or myself.

On receiving her first draft, I was once again struck, not only by her determination in speaking with unflinching precision the horror that would leave us speechless, but by her ability to stay with the internal logic and structure of her collection as she navigates grey no man’s lands of exhaustion, shock and survivor’s guilt. Her spare & lucid language wakes us from the glare of generic livestreamed indignation as she watches bomber planes named for First Nation people murdered in an earlier genocide buzzing overhead, the rude health of soldiers’ bodies and its lethal potential for seductiveness fed by institutionalised robbery, murder and rhetoric, children turning their own fathers’ age in a few seconds.

Observing the daily endurance and human failings of those around her, imagining liberation by utopian transformation or divine intervention (I’m reminded here of Elia Suleiman’s 2002 film of that title), openly voicing her anger and loss, not asking why but fighting absurdity by its own weapons (‘I was wandering the streets in search of a second-hand ceasefire’), Akleen reaches out for a space of shared humanity where life and poetry are welcomed and nurtured. I can only praise her for creating such a space within herself against forbidding conditions and salute her as she takes her place with the fellow poets she honours by her work.

Viti, MMXXIV

Abu Akleen, September 2025

Abu Akleen, September 2025* See Costanza Ferrini (ed.), Di acqua e di tempo /

Of Water and Time (San Marino: AIEP, 2022).

For the attention of ‘brick & mortar’ bookshops,

order copies of Abu Akleen’s 48Kg. via our distributor,

Asterism Books.

SEE HERE FOR AN INTERVIEW WITH AKLEEN ℅ ARAB LIT

INTRODUCING AKLEEN, mpT’s ‘POET IN RESIDENCE, MMXXIV’

TWO POEMS, TRANSLATED BY YASMIN ZAHER, ℅ TRIANGLE HOUSE

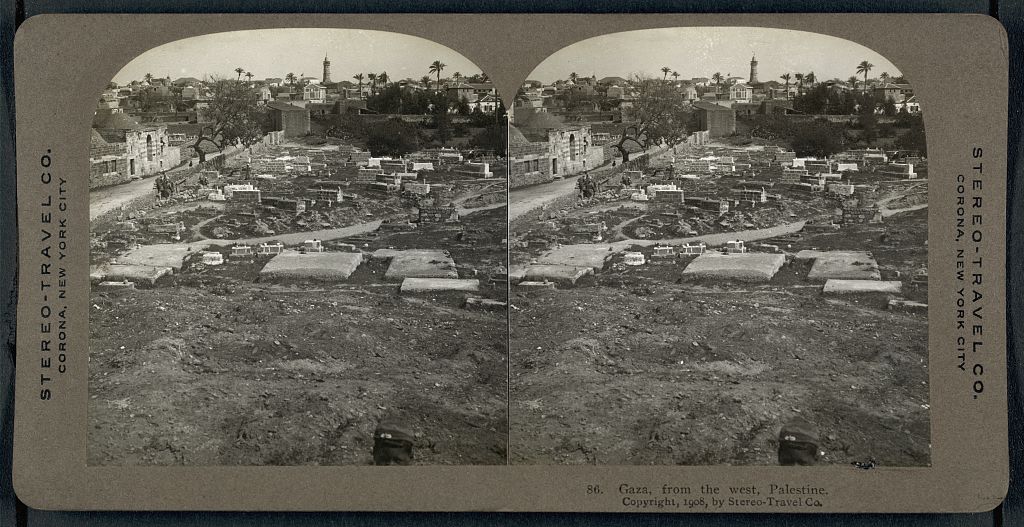

Middle—Gaza, seen from the west

(Corona, New York: Stereo-Travel Co., circa 1908),

℅ the Library of Congress.

Bottom—Samson’s gate, Gaza (circa 1862),

Albumen Print, ℅ the Library of Congress.

Parallel Publications

Left—Abu Akleen’s poem ‘I want a grave,’ as featured in her Tenement debut, 48Kgs, is included in Mohammed Al-Zaqzooq & Mahmoud Alshaer’s anthology, Letters from Gaza (Penguin, 2025), a collection of poetry, letters, and monologues from thirty Gazans.

SEE HERE

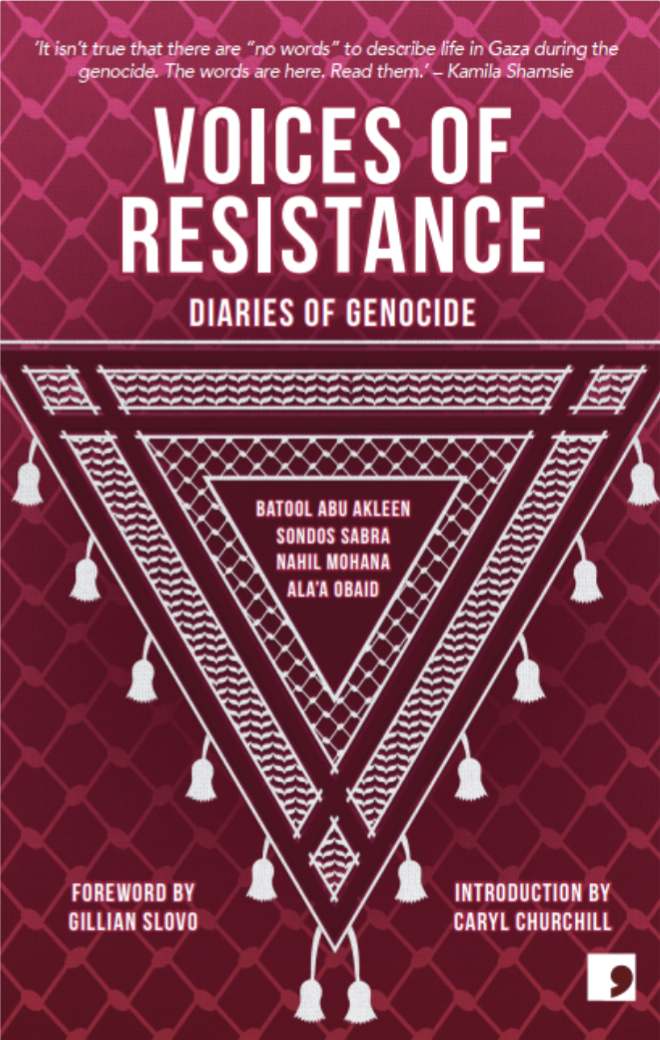

Right—Voices of Resistance: Diaries of a Genocide (Comma Press, 2025) gathers selections of the diaries of four women who have been attempting to share their daily lives through writing:

Nahil Mohana

Sondos Sabra

Ala'a Obaid

Batool Abu Akleen

Trapped in different parts of the Gaza Strip—with commitments to support different members of their immediate family—they have been recording their daily experiences with humour, strength and most of all dignity. Extracts of their diaries have been published in places like the Washington Post, the New Statesman, LitHub and elsewhere.

SEE HERE

SEE HERE

A Palestine Festival of Literature

‘Book of the Week’ /

A Palestine Festival of Literature

‘Bookshelf’ choice.

A New Statesman ‘Book of the Year’ 2025 /

℅ Jacqueline Rose.

Awarded the Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Fellowship / ℅ the Akademie Schloss Solitude.

‘Book of the Week’ /

A Palestine Festival of Literature

‘Bookshelf’ choice.

A New Statesman ‘Book of the Year’ 2025 /

℅ Jacqueline Rose.

Awarded the Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Fellowship / ℅ the Akademie Schloss Solitude.

At just 20 years old, Abu Akleen is becoming one of Gaza's most vivid and unstinting witnesses.

Claire Armistead,

The Guardian

These poems witness dispossession so profound, the poet longs even for certainty that her body will rest in a grave. This searing fact is the heart of 48 Kg.

Anne Michaels

This remarkable debut by a 20-year-old Palestinian, born and raised in Gaza, stands out among poetry of witness on the genocide there. It contains 48 poems, each representing a kilogram of bodyweight, with the book literally thinning as the pages turn. The final poem declares: ‘I die without a voice. / He skins me, flesh from bones. / Cuts me into forty-eight pieces. Distributes the parts in blue plastic bags / & throws them to the four corners.’ Unlike the Muses who buried Orpheus’s dismembered limbs, the poem ends with the paramedic guessing ‘which of these bags / contain my flesh.’ Written in Gaza between 2023 and 2025, Abu Akleen’s poems disassemble and painstakingly reassemble the body to interrogate injustice, death and grief. She creates a world where absurdity and reality, irony and humanity coexist—from the ice-cream man crying out ‘corpses for sale’ while noting that ‘no grave buys them,’ to death wanting to have a birthday party and picking ‘an arm the missile hadn’t shattered.’ Abu Akleen self-translated 38 of the 48 poems, describing the process of translation as making ‘peace with death,‘ while writing in Arabic meant being ‘torn apart without … anyone there to recollect it.’ The book articulates the vital linguistic bridge she establishes in the present between Arabic and English, and includes historical photographs of Gaza from 1863 and 1908 and the 2022 discovery of a fifth-century Byzantine mosaic, highlighting the city’s rich cultural history. Throughout 48Kg, Abu Akleen transforms witnessed details into fragile interpretations: the ‘broken plates they make homes for their younger siblings,’ the ‘moment War became a school,’ and the ‘Ring Finger I lend to the woman who lost / her hand and her husband.’ She notes that poetry gives ‘a form to feelings in order to understand them,’ and these heartbreaking and risk-taking poems protest with uncompromising clarity and tenderness against continuing atrocities.

Kit Fan,

The Guardian

Batool Abu Akleen’s roaming verse contemplates whether absurdism is the only language we have left to express this vicious genocide.

Hasib Hourani

Objects and emotions tangle brilliantly in these searing poems. It’s terrible that Abu Akleen has atrocities to write about, and how well she does it.

Caryl Churchill

Batool Abu Akleen's poetry is both tragic and eloquent. No words can convey Gaza's ordeal, but her spare verses give it a life and meaning beyond words. The lines compel the reader's attention and empathy.

Ghada Karmi

Like lines of Emily Dickinson, Batool Abu Akleen’s astonishing work combines electric imagery with naked-wire directness to say that, when ‘nothing remains but the fire,’ the one thing you can trust is poetry.

Ruth Padel

Praise for Abu Akleen’s 48Kg.

Where prior literary icons mythologised the land or the martyr, Abu Akleen scales Gaza down to the weight of a starving female body. Her poetics are granular, skeletal, and radically intimate. 48Kg. is not merely a title but a structuring device. Each poem is named for a declining weight—48Kg, 47, and so on—transforming the body into a site of measurement and testimony. The architecture of the book is deliberately skeletal: spare verses, minimal punctuation, abrupt line breaks. The effect is not aesthetic minimalism but physiological urgency. Hunger is not abstract here; it becomes the formal logic underwriting the text.

The language is severe, elliptical, and often surreal. In one of the early poems, the speaker confesses, ‘I pick fresh hearts from the street / the most defeated ones,’ rendering grief both grotesque and devotional. The body becomes a terrain of improvisation, where cooking, dreaming, and mourning merge into hybrid rituals. The absence of punctuation throughout the text mirrors the collapse of structure in siege-life. Sentences fracture like walls. Meaning stumbles and reassembles across enjambments.

Central to this work is the gendered experience of survival. Unlike heroic, masculine renderings of martyrdom or battle, Abu Akleen’s voice inhabits the soft infrastructures of war—kitchens, beds, toilets, menstrual blood. In the poem ‘Judgment Day,’ she writes: ‘Gabriel hasn’t blown into his trumpet yet / how did the resurrection happen?’ Her irony isn’t performative. It’s the confusion of a survivor who no longer trusts the calendar of catastrophe. Time in 48Kg. is erratic. Space is claustrophobic. Bodies vanish incrementally rather than explosively. This is a literature not of spectacle but of slow erasure.

In dialogue with other 2024 Gazan texts, such as Letters from Gaza (Penguin, 2025), where collective testimony dominates, Abu Akleen’s singular voice is a rupture. Where Letters archives the many, 48Kg. commits to the irreducible complexity of one. Its formal refusal of narrative cohesion contrasts with the epistolary shape of communal grief. The result is a poetics that does not explain Gaza to the world but carves Gaza into the body of language itself.

Alaa Alqaisi,

The Avery Review

Abu Akleen’s bilingual collection of poems, 48kg, is not solely a powerful literary work; rather, it is a testimony of the genocide that has been wrought upon Gaza for the past two years, written in a poetic verse and style. Her writing is urgent, heartbreaking, honest, and brutal; every line lingers long after reading.

A blend between personal witness and poetic verse, the collection was translated from the Arabic by Akleen herself along with Graham Liddell, Wiam El-Tamami, Cristina Viti, and Yasmin Zaher. The close collaboration ensured that the urgency of her voice was not lost in translation. Indeed, her first-hand experience of the genocidal war on Gaza is not hidden in gentle language, and the bilingual nature of the text puts the original Arabic side-by-side with its English counterparts. In translation, Akleen endeavours to convey her experience of genocide to a broader, non-Arabic speaking audience.

Through her poems, Batool reveals her experiences of the ongoing genocide taking place in Gaza. She wrote, ‘In this book, I am collecting the parts of myself I have found, in case there isn’t anyone there to do so if I am killed.’ Her poems not only represent her personal recollections of the everyday struggle, but also mirror the collective story of the Palestinian people in Gaza and their survival over the last two years. Her narrative voice is both personal and collective, embodying the voices of the countless victims whose names we did not learn. Through this double approach, the poems are both an intimate testimony of Akleen’s experience and a form of collective witness, often blurring the line between the author and the unknown victim.

Indeed, in the two years of genocide, countless Palestinians have been killed by Israel, including writers who have been immortalised by the words they left behind. The martyr Refaat Alareer wrote: ‘If I must die, you must live, to tell my story,’ and Hiba Abu Nada, who also provided her first-hand testimony of genocide before becoming a martyr, wrote in Passages through Genocide: ‘And if we die, to speak on our behalf, there were people here who dreamt of travel and love and life and other things.’ Along with them, thousands of others have lost their voices.

48kg lays bare the atrocities the Palestinian people endure. It does not hide the Zionist intention behind abstractions, but rather confronts us with the stark realities of a genocidal war. Batool writes about ‘images’ that we have all seen over the last two years, images of a genocide live streamed.

Christina Chatzitheodorou,

Asymptote

In Abu Akleen’s 48Kg., lines ebb and flow with a vital pulse, and poems such as ‘The leaving game’ (p. 51), ‘A lesson on colour’ (p. 63) and ‘A trick to escape death’ (p. 77) maximise the space of the page so as to draw other voices into the poet’s breath. Amid all the searing images of the book, occasional lines of iambic pentameter stand out, wielding alliteration and assonance to unforgettable effect:

I sink in mud with strawberries for sale

(p. 31)

blind since the moment War became a school

(p. 63)

The fat stored in my father’s flesh is melting

(p. 75)

how all things in it pass or are awaited

(p. 93)

A busker used to fill our street with boredom

(p. 97)

I sleep & sadness haunts my orphan friend

(p. 103)

he picked an arm the missile hadn’t shattered

(p. 105)

Memorable though these formulations are on their own, I realise that there is yet more violence in severing them from the respective bodies of their poems. After all, Batool Abu Akleen writes of amputation and dismemberment, unbearable suffering and sorrow, in order that she, her people, and her land may yet be re-membered with the love, care and urgency they deserve. As she says in her author’s note, ‘In this book, I am collecting the parts of myself I have found, in case there isn’t anyone there to do so if I am killed’ (p. 21). What a heartrending thing it is to read a debut collection already braced for posterity—yet what a privilege it is to have these extraordinary poems, in spite of all.

Samuel Martin,

Hopscotch Translation

The Palfest Podcast

Batool Abu Akleen in conversation

with Wiam El-Tamami.

See palfest.org/podcast

Bulaq / بولاق

Batool Abu Akleen in conversation

with Marcia Lynx Qualey

& Ursula Lindsay.

Bulaq is co-produced

by the Sout platform.

See arablit.org/podcast

Batool Abu Akleen is a Palestinian poet and translator from Gaza City. At the age of fifteen, 2020, she won the Barjeel Poetry Prize for her poem ‘I didn’t steal the cloud,’ which was published in the Beirut-based magazine Rusted Radishes thereafter. Abu Akleen’s poetry has been translated into several languages and featured in numerous international publications, including ArabLit and The Massachusetts Review, amongst others. Her poem ‘Gunpowder’ was awarded third place in the 2025 London Magazine poetry prize, and her work was included in the July 2024 issue of Modern Poetry in Translation, ‘Salam to Gaza.’ Abu Akleen was Modern Poetry in Translation’s 2024 ‘Poet / Translator in Residence.’ Her poetry has appeared in editors Mohammed Al-Zaqzooq and Mahmoud Alshaer’s anthology, Letters from Gaza (Penguin, 2025) and—alongside Nahil Mohan, Sondos Sabra and Ala’a Obaid— she is one of the four Gazan authors included in Voices of Resistance: Diaries of Genocide (Comma Press, 2025).

Graham Liddell is a writer, translator, and scholar of modern migration literature. His translations from Arabic have appeared in Banipal, ArabLit Quarterly, and The Stinging Fly. In 2022, he edited and contributed to a book-length issue of the literary translation journal Absinthe, entitled Orphaned of Light: Translating Arab & Arabophone Migration. A recent recipient of a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Michigan, Liddell wrote a dissertation on the ways that contemporary Arab and Afghan migration experiences are narrated in both published literature and the asylum process. His current position is Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Hope College.

Wiam El-Tamami is an Egyptian writer, translator and editor. Her work has been featured in publications such as The Paris Review, Granta, Ploughshares, Freeman’s, LitHub, AGNI, ArabLit, CRAFT and The Common, among others. She won the 2011 Harvill Secker Prize, was shortlisted for the 2023 Disquiet International Prize, and received a Pushcart Prize nomination in 2024. She is currently based in Berlin.

Cristina Viti is a translator and poet working with Italian, English and French. Among her recent publications are Pier Paolo Pasolini’s La rabbia / Anger (Tenement Press, 2022), a co-translation of poems by Anna Gréki, The Streets of Algiers and Other Poems (Smokestack Books, 2020), and her translation of Elsa Morante’s The World Saved by Kids and Other Epics (Seagull Books, 2016), which was shortlisted for the John Florio Prize. Viti held collaborative translation workshops within the Radical Translations project run by the French and Comparative Literature departments of King’s College; Tenement’s imprint No University Press published an anthology of texts resulting of these workshops in 2024, An Anarchist Playbook.

Yasmin Zaher is a Palestinian journalist and writer. Her debut novel, The Coin (Catapult / Footnotes)—a New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice—was published in 2024, and awarded the Dylan Thomas Prize, 2025.

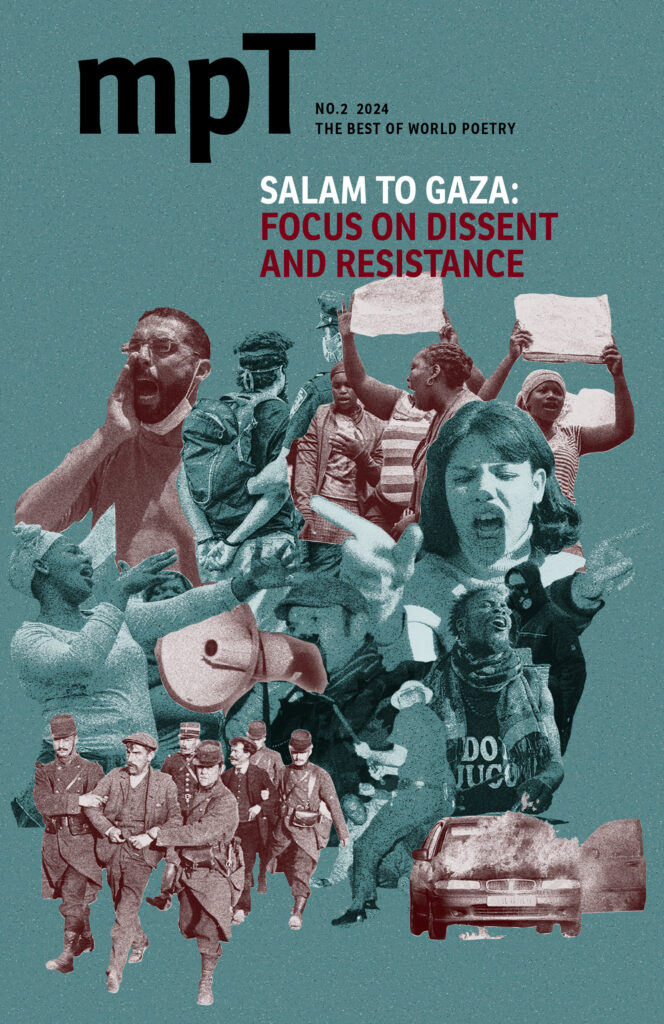

As Modern Poetry in Translation’s 2024 ‘Poet in Residence,’ a thread of translations of Akleen’s poems was published in the Autumn issue of the magazine, ‘Salam to Gaza: Focus on Dissent and Resistance.’

Recently, standing in front of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ‘Landscape with the Flight into Egypt,’ at the Courtauld gallery, my friend and I were discussing Raymond Geuss’s argument about the moral choice of locating oneself in a painting as opposed to being a viewer.

The question is: should we see ourselves as the characters in the painting, take a side, or maybe even implicate ourselves? I wondered if the predicament applies to poetry. We’re all sophisticated enough to know that the “you” isn’t you, and the “I” isn’t I, but could we, as readers, locate ourselves in a poem? This is to go further than merely identifying with an emotion or a sensibility. Choosing a position in the poem would be akin to choosing a position in the world: viewer or participant?

From Janani Ambikapathy’s

editorial introduction to the issue.