El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel /

Juan Ángel’s Birthday

Mario Benedetti

Translated from the Spanish

by Adam Feinstein

Tenement Press #11

978-1-7393851-2-5

317pp

£18.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 22nd April 2024

![]()

![]()

Left—A march (Montevideo, Uruguay),

‘Esperando al guerrillero,’ Época (1965).

Written in 1970—three years prior to Uruguay’s descent into dictatorship—we follow our protagonist, Osvaldo Puente, as he adopts a nom de guerre, Juan Ángel, and joins the guerrilla on the front line. It is Puente’s birthday, and he is eight years old. As the hours shuttle by, the minutes turn to months, and—over the course of a single day—we see Puente sprint toward adulthood at pace. Cue a kaleidoscope of familial bonds stretched to breaking point, fractal agency, a curt dismantling of class, a weather system of love affairs and a withering of friendships, as Puente changes his name as evening draws in, aged thirty-three, with his commitment to the guerrilla’s cause ossified.

A single monologue in verse—thatching politics, pop culture, and a child’s eye on a world requiring constant decipherment—Feinstein’s translation of Benedetti’s El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel is a brutal and searing rendition of the quick sophistication of a political outlook and an ideological ‘id’ in times of strife, need, and change.

For the attention of ‘brick & mortar’ bookshops,

order copies of Benedetti’s Juan Ángel via our

distributor, Asterism Books.

Juan Ángel’s Birthday

Mario Benedetti

Translated from the Spanish

by Adam Feinstein

Tenement Press #11

978-1-7393851-2-5

317pp

£18.50

ORDER DIRECT FROM TENEMENT HERE

Published 22nd April 2024

We must be accountable to every day.

Mario Benedetti

Mario Orlando Hamlet Hardy Brenno Benedetti Farugia—otherwise known as Mario Benedetti (1920-2009)—was a Uruguayan novelist, journalist, activist, and poet. A key member of the Generación del 45, Benedetti is oft celebrated throughout Latin America for his ‘direct’ verse, his poetry and prose focusing on complicity, on the acuity of ‘love, anger, and resistance’ in moments of political and civil unrest and upheaval (The Guardian).

A frequent contributor to the Uruguayan weekly, Marcha, Benedetti was instrumental in the establishment of the Frente Amplio / Broad Front movement, which sought to unify left-wing groups in 1960s Uruguay, and his writing has been translated into over eighty languages. Awarded the Reina Sofía Prize for Poetry (1999) and the Ibero-American José Martí Prize (2000), his novels have been adapted for the cinema (see La tregua / The Truce, 1960) and his poetry set to music by such artists as Catalan singer-songwriter Joan Manuel Serrat (notably on Serrat’s album El sur tambien existe / The south also exists, a passionate indictment of US foreign policy).

El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel / Juan Angel's birthday, published by Tenement Press in a first-time English language edition translated and annotated by Adam Feinstein, crystallises its author’s life-long efforts to explore the pluralist politics of care, and individual experience via a monologic study of the quickening of childhood, of innocence, and of adolescence against the backdrop of revolution and Uruguay’s Tupamaro guerrilla movement.

Mario Benedetti

Mario Orlando Hamlet Hardy Brenno Benedetti Farugia—otherwise known as Mario Benedetti (1920-2009)—was a Uruguayan novelist, journalist, activist, and poet. A key member of the Generación del 45, Benedetti is oft celebrated throughout Latin America for his ‘direct’ verse, his poetry and prose focusing on complicity, on the acuity of ‘love, anger, and resistance’ in moments of political and civil unrest and upheaval (The Guardian).

A frequent contributor to the Uruguayan weekly, Marcha, Benedetti was instrumental in the establishment of the Frente Amplio / Broad Front movement, which sought to unify left-wing groups in 1960s Uruguay, and his writing has been translated into over eighty languages. Awarded the Reina Sofía Prize for Poetry (1999) and the Ibero-American José Martí Prize (2000), his novels have been adapted for the cinema (see La tregua / The Truce, 1960) and his poetry set to music by such artists as Catalan singer-songwriter Joan Manuel Serrat (notably on Serrat’s album El sur tambien existe / The south also exists, a passionate indictment of US foreign policy).

El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel / Juan Angel's birthday, published by Tenement Press in a first-time English language edition translated and annotated by Adam Feinstein, crystallises its author’s life-long efforts to explore the pluralist politics of care, and individual experience via a monologic study of the quickening of childhood, of innocence, and of adolescence against the backdrop of revolution and Uruguay’s Tupamaro guerrilla movement.

Left—A march (Montevideo, Uruguay),

‘Esperando al guerrillero,’ Época (1965).

Right—A demonstration against the

coup d'état in Uruguay, Montevideo,

9 July 1973, Aurelio Gonzalez, © 2024.

coup d'état in Uruguay, Montevideo,

9 July 1973, Aurelio Gonzalez, © 2024.

Written in 1970—three years prior to Uruguay’s descent into dictatorship—we follow our protagonist, Osvaldo Puente, as he adopts a nom de guerre, Juan Ángel, and joins the guerrilla on the front line. It is Puente’s birthday, and he is eight years old. As the hours shuttle by, the minutes turn to months, and—over the course of a single day—we see Puente sprint toward adulthood at pace. Cue a kaleidoscope of familial bonds stretched to breaking point, fractal agency, a curt dismantling of class, a weather system of love affairs and a withering of friendships, as Puente changes his name as evening draws in, aged thirty-three, with his commitment to the guerrilla’s cause ossified.

A single monologue in verse—thatching politics, pop culture, and a child’s eye on a world requiring constant decipherment—Feinstein’s translation of Benedetti’s El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel is a brutal and searing rendition of the quick sophistication of a political outlook and an ideological ‘id’ in times of strife, need, and change.

order copies of Benedetti’s Juan Ángel via our

distributor, Asterism Books.

A monument to Raúl Sendic in Trinidad, Uruguay

Read Feinstein’s afterword

to the Tenement edition,

‘Mario Benedetti, the Reluctant Optimist,

and his Strange Beast’ here ...

William Cordova, ‘Tupamaros, after Raúl Sendic’ (2007/2008),

William Cordova, ‘Tupamaros, after Raúl Sendic’ (2007/2008), Whitney Museum of American Art (New York City, NY)

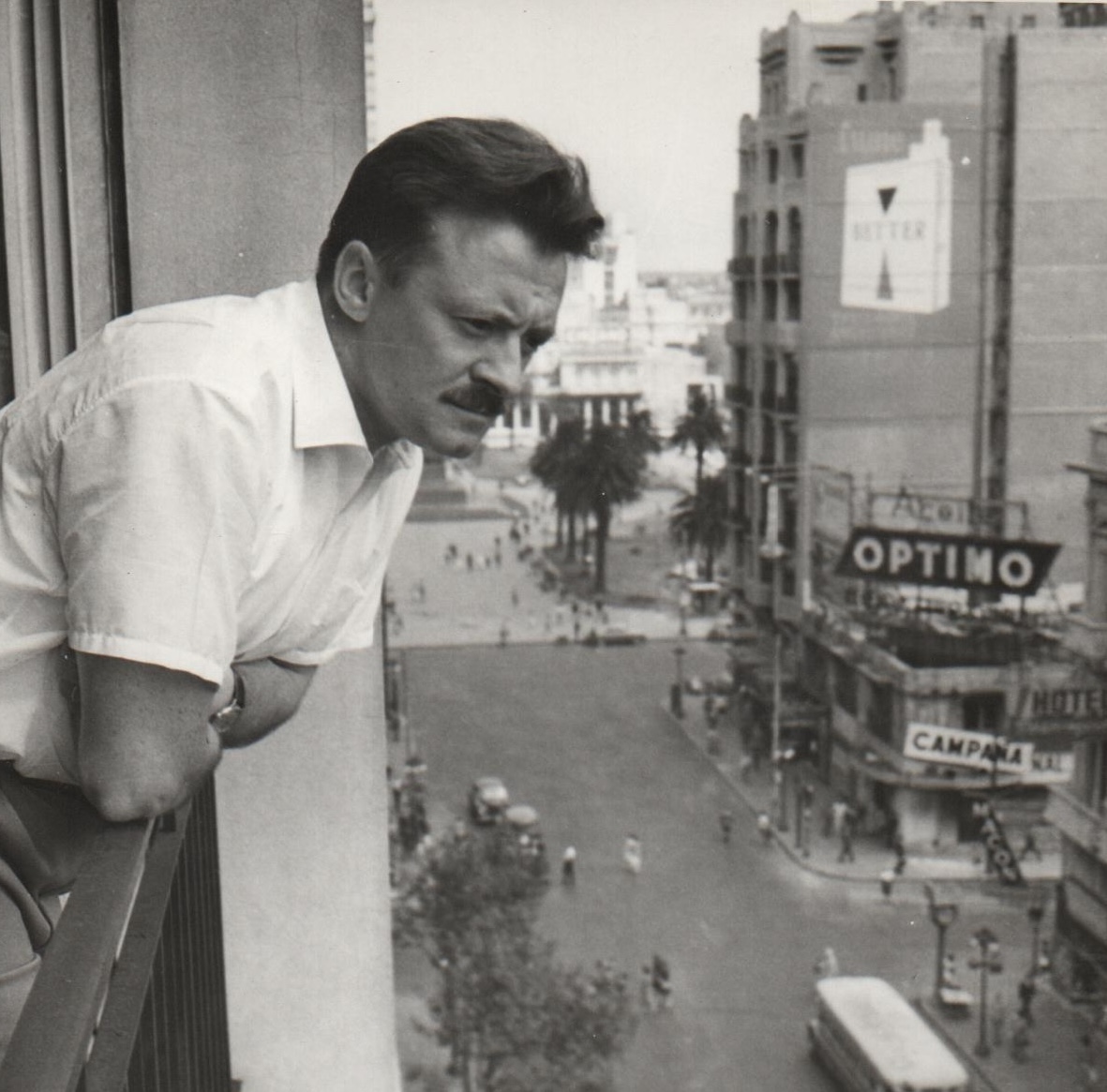

Mario Benedetti, Montevideo, 1963 /

Fundación Benedetti, © 2024.

Fundación Benedetti, © 2024.

It’s extremely difficult to find a poem which fulfils the condition of a novel and a lyrical text without betraying both. El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel achieves this feat through experimental verse. It’s an extraordinary river-poem in which, without abandoning the nucleus of poetic art, Benedetti takes the genre of militancy and the pamphlet a step further. As if a true Ovid’s Metamorphoses, or Kafka’s Metamorphosis, the protagonist passes through different stages as revolutionary as they are imbued with a biblical, epic quality. It is so fortunate for all those discerning English-speaking readers that this book is now published.

Agustín Fernández Mallo

Set in Montevideo [El cumpleaños de El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel / Juan Ángel's Birthday] traces the revolutionary discovery of Osvaldo Puente, who becomes the guerrillero Juan Angel. Benedetti’s writing—concise, lyrical, irrepressible—charts ideological and spiritual discovery. Feinstein’s translation preserves the electrifying power of the Spanish original, and his accompanying essay sets the novel’s continuing relevance against the background of political upheaval in 1970s Uruguay. Benedetti reminds us that revolution is not only a historical force but a deeply personal metamorphosis: ‘I’ve turned hard in this sudden half-shadow/ of the revolution […] the owl and the flamingo are no longer my omens/ nor my jubilation/ but no more than my beloved heirlooms.’ A haunting, masterful work—part Bildungsroman, part political lament, and wholly unmissable.

Leo Boix,

The Morning Star

Benedetti’s rhythms are intensely local, whether replicating bar-room chat or Argentine tangos. He incorporates anglicisms, words from lunfardo (a dialect originating among the working class of early-twentieth-century Buenos Aires) and his own amusing neologisms. In this translation Adam Feinstein, the biographer of Pablo Neruda, captures both the humour and the humility of the original, and finds neat counterparts for the wordplay.

[...]

The leftist insurgency movements of Latin America in the 1970s, and their brutal repression by secret state forces, have given rise to many accounts, both factual (Jacobo Timerman’s Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, 1981) and fictional (Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden, 1990). None that I have read comes closer than El cumpleaños de Juan Ángel to conveying the transformation, which took place in thousands of households, from middle-class to militant. Mario Benedetti’s poem has long had a following in South America—the Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos even took his name from the guerrilla character. It’s a pleasure to see it reprinted alongside this sympathetic translation.

Miranda France,

The Times Literary Supplement

The work of Mario Benedetti, my friend and brother, is surprising in all its aspects, whether the varied extent of genres it touches, the density of its poetic expression or the extreme conceptual freedom it employs.

José Saramago

This forgotten novel in verse follows the Montevidean bourgeois life of Juan Ángel's successive birthdays and his transformation into a Guevarist revolutionary in a style that fuses slang and rage, tango rhythms and avantgarde word-play, agilely and vividly translated by Adam Feinstein, so that we understand Benedetti's class values and his transformation into a fearless underground guerrilla revolutionary, which today maybe reads nostalgically for a lost youth, but at the time in 1970 was a brave call to arms before the guerrilla dream soured.

Jason Wilson

In Latin America and Spain, he is remembered above all as a poet who sought to speak of love and political commitment as directly and passionately as possible. By the end of his life, he had published more than 80 books, and in one of his last poems he gave the instructions: When I’m buried / don’t forget to put a Biro in my coffin.

Nick Caistor,

The Guardian

Benedetti was one of Uruguay’s most beloved poets and activists.

World Literature Today

Benedetti’s poetry enters like gentle, familiar music. And we recognise ourselves. It’s like a mirror which, under a special light, offers us a new image of ourselves, more intense and true. It does not matter how long Benedetti has spent working and re-working these lines, polishing them, correcting them, destroying them and re-writing them—as was his wont throughout his life. The important thing is that the result is so limpid and immediate.

Martha Canfield

Benedetti has crafted a portrait of the ‘long parenthesis’ opened up in Uruguay’s society, from which ‘nobody will be able to pick up the thread of the original sentence.’

New York Times Book Review

Benedetti is one of Latin America’s most highly renown and beloved authors who wrote (especially) about everyday life in Montevideo. Using well-balanced and appropriate doses of humor and colloquialisms, he showed a deep and poignant insight into his characters’ inner world and captured the problems of the city dwellers, who while trapped in an impersonal world, are building a shell to protect themselves from authentic feelings.

Harry Morales, Brooklyn Rail

Present-Day reality in Latin America, where stereotypes of chaos and repression are at once outdated and true, provides its authors with abundant material for what continues to be an estimable literary production. Political struggles there, of little interest to the rest of the world prior to the triumph of Fidel Castro in Cuba but a supreme fact of life since Independence, perforce engage the writer's attention, especially one whose concentration has been unswervingly on his fellow citizens and national attitudes. Such an author is Mario Benedetti—novelist, poet, essayist, and one of Latin America's most widely-read short story writers. Beginning in 1960, Benedetti began to use his fictions and essays as instruments to analyse the political crises in Latin America and, specifically, the decline in morality and leadership of his own nation. [...] His insistence on a commitment to political change in Latin America and the elimination of ruthless oligarchies has often been stated. But equally insistent is his repeated declaration that literature must remain literature, an artful shaping of human experience; that political propaganda passed off as art works against the author's purpose. Given his unwavering stand, we may conclude with some assurance that Benedetti, forever the creator, sees the artistic possibilities in putting dispirited characters into a politically charged environment and allowing them to be energised by it.

Latin American Literary Review

Mario Orlando Hamlet Hardy Brenno Benedetti, known as Mario Benedetti, was a Uruguayan journalist, novelist, and poet. He is considered one of the most important 20th century Latin American writers, especially in the Spanish-speaking world. A revolutionary and a passionate romantic, Benedetti wrote of love, anger, political resistance and redemption, particularly during the period of his enforced exile from Uruguay, between 1973 and 1985.

Adam Feinstein is an acclaimed British author, poet, translator, Hispanist, journalist, screenwriter, film critic and autism researcher. His biography of the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda: A Passion for Life, was first published by Bloomsbury in 2004 and reissued in an updated edition in 2013 (Harold Pinter called it ‘a masterpiece’). Arc published his new book of translations, The Unknown Neruda, in 2019 and another book of translations, this time of the great Nicaraguan poet, Rubén Darío, came out in two separate editions in 2020, first in Nicaragua itself and then by Shearsman in the UK. He has also published a collection of translations of the Cuban poet, José Martí. Feinstein has given numerous lectures around the world, including Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, Guatemala, the United States, Russia, China, India, Spain, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. He broadcasts regularly for the BBC and writes for the Guardian, the Observer, the Financial Times and the Times Literary Supplement. His own poems and his translations (of Neruda, Federico García Lorca, Mario Benedetti, Roque Dalton and others) have been praised for their ‘power and possession’ and their ‘compelling fluency’ and have appeared in many magazines, including Agenda, Acumen, PN Review, Poem and Modern Poetry in Translation.

Adam Feinstein is an acclaimed British author, poet, translator, Hispanist, journalist, screenwriter, film critic and autism researcher. His biography of the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda: A Passion for Life, was first published by Bloomsbury in 2004 and reissued in an updated edition in 2013 (Harold Pinter called it ‘a masterpiece’). Arc published his new book of translations, The Unknown Neruda, in 2019 and another book of translations, this time of the great Nicaraguan poet, Rubén Darío, came out in two separate editions in 2020, first in Nicaragua itself and then by Shearsman in the UK. He has also published a collection of translations of the Cuban poet, José Martí. Feinstein has given numerous lectures around the world, including Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, Guatemala, the United States, Russia, China, India, Spain, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. He broadcasts regularly for the BBC and writes for the Guardian, the Observer, the Financial Times and the Times Literary Supplement. His own poems and his translations (of Neruda, Federico García Lorca, Mario Benedetti, Roque Dalton and others) have been praised for their ‘power and possession’ and their ‘compelling fluency’ and have appeared in many magazines, including Agenda, Acumen, PN Review, Poem and Modern Poetry in Translation.