Rehearsal / 54. Cesare Pavese

![]()

I need myths, fantastical and universal, to fully and unforgettably

express this experience that is my place in the world.

Cesare Pavese, from a letter

to Fernanda Pivano (June 27, 1940).

![]()

Excerpts from Pavese’s Leucothea Dialogues

(Archipelago Books, 2025) translated from the

Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor. Order direct

from the press here.

‘Given the choice, a person could certainly get by with less mythology. But we’ve come to accept mythology as a language, an expressive mode—which is to say, it’s not random, it’s a hothouse of symbols that belongs, like all languages do, to a specific set of references that can’t be conveyed any other way. When we repeat a proper noun, an action, a mythical feat, we are expressing—in short, with simplicity—a synthetic and comprehensive fact, a kernel of reality that brings to life and nurtures an entire organism of passion, of the human condition, the entirety of a conceptual framework. If the noun or gesture reminds us of childhood or our schooldays, all the better. Disquiet is more real and pointed when stirring up the familiar. What’s immediate and conventional about the Greek myths, how understandably popular they are, is adequate for us. We’re so frightened of the irregular, abnormal, or coincidental, and we go to great, even physical, lengths to establish limits and perimeters—to make sure whatever it is will be over and done with. We’ve grown convinced that great revelations can only be drawn from the stubborn rehashing of the same problems. We’re nothing like world travelers, inventors, or adventurers. We know that the best and quickest path to surprise is to stare fearlessly and steadily at the same object. Then—there is that perfect moment when, miracle of miracles, that same object will seem like something we’ve never seen before.’

Pavese, 1947

I need myths, fantastical and universal, to fully and unforgettably

express this experience that is my place in the world.

Cesare Pavese, from a letter

to Fernanda Pivano (June 27, 1940).

Excerpts from Pavese’s Leucothea Dialogues

(Archipelago Books, 2025) translated from the

Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor. Order direct

from the press here.

‘Given the choice, a person could certainly get by with less mythology. But we’ve come to accept mythology as a language, an expressive mode—which is to say, it’s not random, it’s a hothouse of symbols that belongs, like all languages do, to a specific set of references that can’t be conveyed any other way. When we repeat a proper noun, an action, a mythical feat, we are expressing—in short, with simplicity—a synthetic and comprehensive fact, a kernel of reality that brings to life and nurtures an entire organism of passion, of the human condition, the entirety of a conceptual framework. If the noun or gesture reminds us of childhood or our schooldays, all the better. Disquiet is more real and pointed when stirring up the familiar. What’s immediate and conventional about the Greek myths, how understandably popular they are, is adequate for us. We’re so frightened of the irregular, abnormal, or coincidental, and we go to great, even physical, lengths to establish limits and perimeters—to make sure whatever it is will be over and done with. We’ve grown convinced that great revelations can only be drawn from the stubborn rehashing of the same problems. We’re nothing like world travelers, inventors, or adventurers. We know that the best and quickest path to surprise is to stare fearlessly and steadily at the same object. Then—there is that perfect moment when, miracle of miracles, that same object will seem like something we’ve never seen before.’

Pavese, 1947

BEAST / BULL

![]()

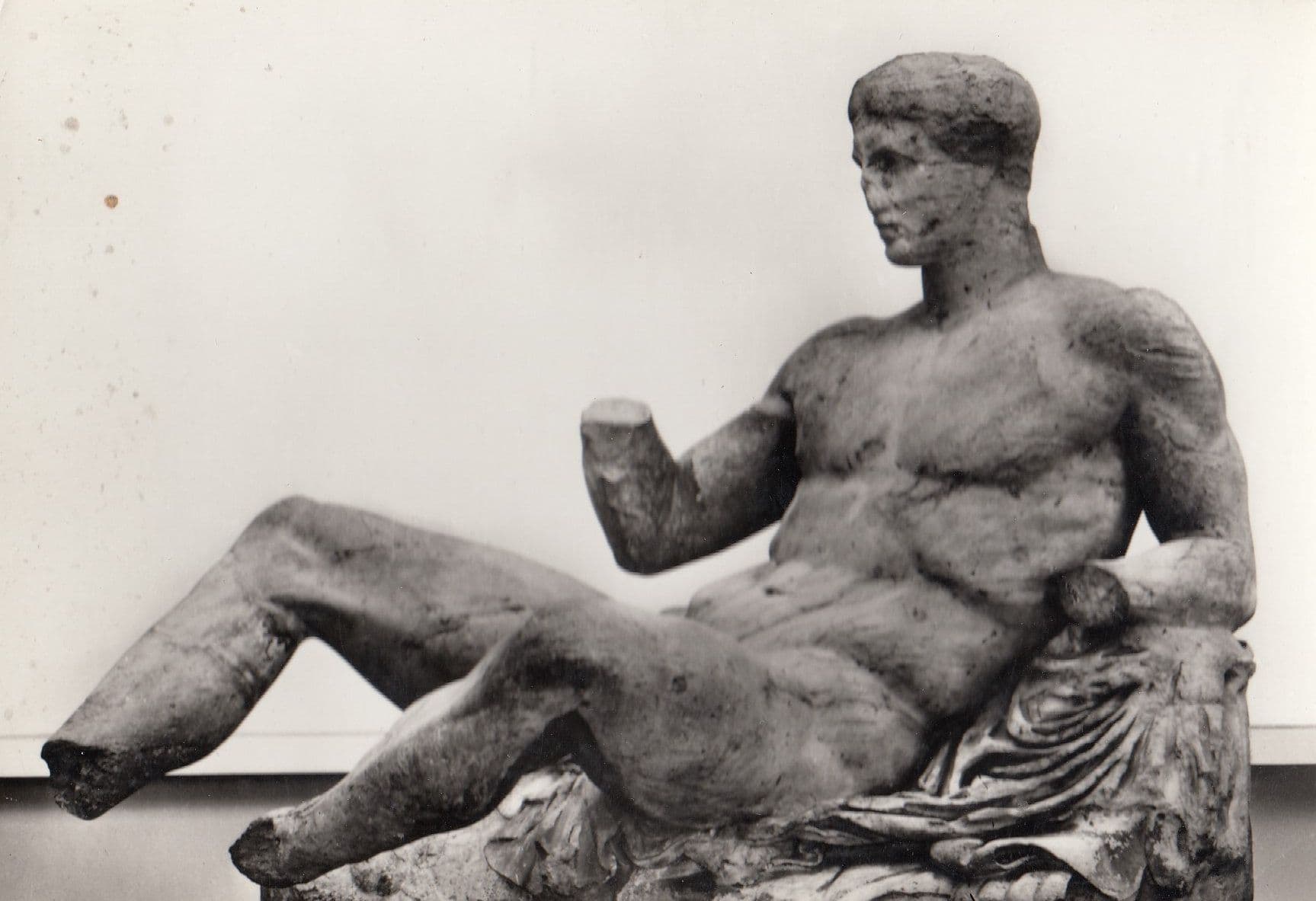

Endymion

(British Museum).

BEAST ENDYMION & A STRANGER

We believe Artemis’s love for Endymion wasn’t carnal. And yet that doesn’t

exclude the very real possibility that the feebler of the two lusted for blood.

The virgin goddess is known for her unwholesome character—she who ruled

the beasts and came into the world from the forbidden dark forest of divine

mothers of the monstrous Mediterranean. Just as it is known that a person

who can’t sleep wants to sleep and goes down in history as the eternal

dreamer.

ENDYMION

You—walking by—can we talk? I can talk to you because you’re not from around here. Don’t worry about the madness in my eyes, the rags on your feet are as disreputable. But you seem like a serious man who will eventually settle down in some nice village, where you will relax, find work and a home—because that’s what you want. And yet I’m pretty sure you wander now because all you have is fate. You walk these roads at dawn, which must mean that you like to be awake when things are just emerging from the night, still untouched. You see Mount Latmus over there? I go up there all the time at night, when it’s darkest, and wait among the beech trees for dawn. And yet I feel like I’ve never stepped foot there.

STRANGER

Who can claim he’s stepped everywhere he’s been, anyway?

ENDYMION

I think sometimes we’re impalpable, like the rushing wind. Or like the dreams of a sleeping person. Do you like to sleep during the day, stranger?

STRANGER

Well, whenever. If I’m tired, I sleep.

![]()

BULL LELEGO & THESEUS

We all know that Theseus, on his way back from Crete, somehow

Endymion

(British Museum).

BEAST ENDYMION & A STRANGER

We believe Artemis’s love for Endymion wasn’t carnal. And yet that doesn’t

exclude the very real possibility that the feebler of the two lusted for blood.

The virgin goddess is known for her unwholesome character—she who ruled

the beasts and came into the world from the forbidden dark forest of divine

mothers of the monstrous Mediterranean. Just as it is known that a person

who can’t sleep wants to sleep and goes down in history as the eternal

dreamer.

ENDYMION

You—walking by—can we talk? I can talk to you because you’re not from around here. Don’t worry about the madness in my eyes, the rags on your feet are as disreputable. But you seem like a serious man who will eventually settle down in some nice village, where you will relax, find work and a home—because that’s what you want. And yet I’m pretty sure you wander now because all you have is fate. You walk these roads at dawn, which must mean that you like to be awake when things are just emerging from the night, still untouched. You see Mount Latmus over there? I go up there all the time at night, when it’s darkest, and wait among the beech trees for dawn. And yet I feel like I’ve never stepped foot there.

STRANGER

Who can claim he’s stepped everywhere he’s been, anyway?

ENDYMION

I think sometimes we’re impalpable, like the rushing wind. Or like the dreams of a sleeping person. Do you like to sleep during the day, stranger?

STRANGER

Well, whenever. If I’m tired, I sleep.

ENDYMION

And when you sleep, wanderer, do you ever listen to the wind blowing, or the birds, or swamps, the bustle, the water’s voice? Have you ever felt that when you’re sleeping, you’re never alone?

STRANGER

I wouldn’t know, friend. I’ve always been on my own.

ENDYMION

I get no peace from sleep, stranger.

I always think I’ve been sleeping but I know it’s not true.

STRANGER

You seem in good shape to me—and strong.

ENDYMION

I am, I am. And I know the sleep of wine, and that deep sleep at a woman’s side. But none of that does me any good. Now, when I go to sleep, my ears are always perked, and my eyes—I have these eyes, like a man who stares into the darkness. I feel like I’ve always been this way.

STRANGER

Have you lost someone?

ENDYMION

Someone? Oh stranger, do you really think we’re mortal?

STRANGER

Someone died on you?

ENDYMION

Not someone ... When I go up Mount Latmus, I stop being mortal. Don’t look at my eyes, they don’t count. I know I’m not dreaming—it’s been so long since I’ve slept. You see that clump of trees, up on the cliff ? That’s where I was last night, waiting for her.

STRANGER

Who were you waiting for?

ENDYMION

Let’s not name her. We will not say her name. She has no name. Or maybe she has too many. My friend, do you know how terrifying the forest is when a nocturnal glen opens up? No? Imagine the nocturnal glen, some place you passed through during the day—there’s a pretty flower, some berry bushes over there rustling in the breeze, more berries, this flower—it’s a wild, untouchable, mortal thing among wild things. Get it? A flower that’s like a wild animal? My friend, have you ever felt both fear of and desire for the essence of a she-wolf, or a doe, or a snake?

STRANGER

You mean, lust for a wild animal?

ENDYMION

Yes, but not just that. Have you ever known someone who was many things at once, who contains all—every gesture, every thought you’ve had about her—she holds vast things from your world, your sky, and your words, memories, days past you’ll never know, future days, everything you’re sure of, and another world, another sky that you can’t have?

STRANGER

I’ve heard talk of such things.

ENDYMION

And, what if this person were the beast, the wild thing ...

The untouchable nature that has no name? STRANGER

What dreadful things you’re saying.

ENDYMION

But that’s not all. You should listen to me. When you set back out on the road, you should know the earth is full of divinity and horror. If I tell you all this it’s because you and I, as travelers and strangers, we have a little divinity of our own, too.

STRANGER

Of course I have seen many things. And some of them dreadful. But you don’t need to cross great distances. If it helps, I can tell you that immortals also feel the lure of the hearth.

ENDYMION

So you do know, and you believe me! I was napping one night on Latmus—it was dark—I had been out late walking, and I fell asleep sitting against a tree trunk. When I woke the moon was high—but in my dream I shivered slightly at the notion that I was there in the glen and then I saw her. She was watching me, with those slightly unfocused but steady eyes—transparent and vast. I didn’t know it then, or even the next day, but I already belonged to her. I’d come into her sights, the space she occupies, the glen, the mountain. She barely smiled at me, and I said, ‘My lady,’ which made her frown like a feral girl, like she’d figured out that I was in her thrall, and I was a little dismayed to have called her a lady. Then an uneasiness hung between us.

She said my name, stranger, and came closer—her tunic was short, above her knees—she reached out and touched my hair. She was almost hesitant, and then she really smiled. It was an incredible smile. It seemed mortal. I was about to bow down, rehearsing all her different names, but she stopped me, the way you stop a child, put her hand under my chin. You can see that I’m a big, strong man, but she was proud and had those eyes—she was just a thin, wild girl—and I was like a little boy. ‘You must never wake up,’ she told me.

‘You don’t have to do a thing. I will come find you.’ Then she crossed the glen and disappeared.

That whole night I walked Mount Latmus. I followed the moon into every stream, into crevices, up to the peaks. My ears were alert but full, like with the ocean, full of that cold, raspy, motherly voice. I stopped at every rustling or shadow. I could only see the flight of wild animals. When dawn came, with its bruised, veiled light, I looked down at this plain—at this road we’re walking together now, and I knew that I would never again live among men. I was no longer one of them. I would wait for nightfall.

STRANGER

What remarkable stories you tell, Endymion. And what’s really remarkable is that you undoubtedly went back up the mountain, and you walk there and live there now and yet this wild creature, the woman with many names, still hasn’t made you hers.

ENDYMION

Stranger, I am hers.

STRANGER

I meant to say ... Haven’t you heard the story about her and the shepherd, who was ripped apart by dogs for his indiscretion ... the man-stag?

ENDYMION

I know everything about her, stranger. Because we have talked and talked while I pretend to sleep. It’s like that every night, and I haven’t touched her, the way you wouldn’t touch a lioness or the green water in a pond, or that which is more yours than anything and holds your heart. Listen. She stands before me—this thin, unsmiling girl—and she watches me. Her vast, transparent eyes have seen so much. Still see. Possessing with those eyes. There’s a berry in her eyes and there’s the beast, there is screaming and death, the cruel entreaty.

I know this bloodshed, this torn flesh, the ravenous earth, the solitude. For her, savage goddess, this is solitude. For her, the beast is solitude. She touches me the way one would pet a dog or feel the trunk of a tree. But she watches me. This thin girl in a short tunic, so much like any girl you’d see in your own village.

STRANGER

Endymion, haven’t you told her anything about your life as a man?

ENDYMION

Stranger, you know such dreadful things and yet you don’t know that the savage and the divine cancel out the man?

STRANGER

I know that when you go up Latmus you stop being mortal. But immortals know how to be alone. And you dislike solitude. You look for sex in beasts. You pretend to sleep when she’s there. What exactly have you asked of her?

ENDYMION

If she would only smile again.

I would bleed for her, be the flesh in her dog’s mouth.

STRANGER

And how does she answer?

ENDYMION

She says nothing. She watches me. She leaves me alone at dawn. And I search for her among the trees. The daylight hurts my eyes. ‘You should never wake up,’ she tells me.

STRANGER

Mortal man, the day you are truly awake is the day you will know why she’s protected you from her smile.

ENDYMION

I already know, stranger, Stranger who talks like a god.

STRANGER

The earth is crowned by both the divine and the awful, and we walk these roads. You’ve been saying that very thing.

ENDYMION

Oh itinerate god, her tenderness is like dawn, it is the earth and sky revealed. It is divinity. But toward the others, the things and beasts—the savage has a brusque laugh and a vicious rule. No one has ever touched her knee.

STRANGER

Endymion, let your mortal heart settle. Neither god nor man has touched it. Her raspy, motherly voice is everything and all that savage can ever give you.

ENDYMION

And yet.

STRANGER

And yet?

ENDYMION

As long as the mountain is there, I will not sleep in peace.

STRANGER

Everyone has their own kind of sleep, Endymion. Your sleep is a plethora of voices, cries, of earth, sky, days. Sleep with courage, you have nothing else worthwhile. Savage solitude is yours. Love her like she loves. And now, Endymion, I must leave you. You will see her tonight.

ENDYMION

Thank you, itinerant god.

STRANGER

Farewell. And remember, you must never again wake up.

And when you sleep, wanderer, do you ever listen to the wind blowing, or the birds, or swamps, the bustle, the water’s voice? Have you ever felt that when you’re sleeping, you’re never alone?

STRANGER

I wouldn’t know, friend. I’ve always been on my own.

ENDYMION

I get no peace from sleep, stranger.

I always think I’ve been sleeping but I know it’s not true.

STRANGER

You seem in good shape to me—and strong.

ENDYMION

I am, I am. And I know the sleep of wine, and that deep sleep at a woman’s side. But none of that does me any good. Now, when I go to sleep, my ears are always perked, and my eyes—I have these eyes, like a man who stares into the darkness. I feel like I’ve always been this way.

STRANGER

Have you lost someone?

ENDYMION

Someone? Oh stranger, do you really think we’re mortal?

STRANGER

Someone died on you?

ENDYMION

Not someone ... When I go up Mount Latmus, I stop being mortal. Don’t look at my eyes, they don’t count. I know I’m not dreaming—it’s been so long since I’ve slept. You see that clump of trees, up on the cliff ? That’s where I was last night, waiting for her.

Who were you waiting for?

ENDYMION

Let’s not name her. We will not say her name. She has no name. Or maybe she has too many. My friend, do you know how terrifying the forest is when a nocturnal glen opens up? No? Imagine the nocturnal glen, some place you passed through during the day—there’s a pretty flower, some berry bushes over there rustling in the breeze, more berries, this flower—it’s a wild, untouchable, mortal thing among wild things. Get it? A flower that’s like a wild animal? My friend, have you ever felt both fear of and desire for the essence of a she-wolf, or a doe, or a snake?

STRANGER

You mean, lust for a wild animal?

ENDYMION

Yes, but not just that. Have you ever known someone who was many things at once, who contains all—every gesture, every thought you’ve had about her—she holds vast things from your world, your sky, and your words, memories, days past you’ll never know, future days, everything you’re sure of, and another world, another sky that you can’t have?

STRANGER

I’ve heard talk of such things.

ENDYMION

And, what if this person were the beast, the wild thing ...

The untouchable nature that has no name?

What dreadful things you’re saying.

ENDYMION

But that’s not all. You should listen to me. When you set back out on the road, you should know the earth is full of divinity and horror. If I tell you all this it’s because you and I, as travelers and strangers, we have a little divinity of our own, too.

STRANGER

Of course I have seen many things. And some of them dreadful. But you don’t need to cross great distances. If it helps, I can tell you that immortals also feel the lure of the hearth.

ENDYMION

So you do know, and you believe me! I was napping one night on Latmus—it was dark—I had been out late walking, and I fell asleep sitting against a tree trunk. When I woke the moon was high—but in my dream I shivered slightly at the notion that I was there in the glen and then I saw her. She was watching me, with those slightly unfocused but steady eyes—transparent and vast. I didn’t know it then, or even the next day, but I already belonged to her. I’d come into her sights, the space she occupies, the glen, the mountain. She barely smiled at me, and I said, ‘My lady,’ which made her frown like a feral girl, like she’d figured out that I was in her thrall, and I was a little dismayed to have called her a lady. Then an uneasiness hung between us.

She said my name, stranger, and came closer—her tunic was short, above her knees—she reached out and touched my hair. She was almost hesitant, and then she really smiled. It was an incredible smile. It seemed mortal. I was about to bow down, rehearsing all her different names, but she stopped me, the way you stop a child, put her hand under my chin. You can see that I’m a big, strong man, but she was proud and had those eyes—she was just a thin, wild girl—and I was like a little boy. ‘You must never wake up,’ she told me.

‘You don’t have to do a thing. I will come find you.’ Then she crossed the glen and disappeared.

That whole night I walked Mount Latmus. I followed the moon into every stream, into crevices, up to the peaks. My ears were alert but full, like with the ocean, full of that cold, raspy, motherly voice. I stopped at every rustling or shadow. I could only see the flight of wild animals. When dawn came, with its bruised, veiled light, I looked down at this plain—at this road we’re walking together now, and I knew that I would never again live among men. I was no longer one of them. I would wait for nightfall.

STRANGER

What remarkable stories you tell, Endymion. And what’s really remarkable is that you undoubtedly went back up the mountain, and you walk there and live there now and yet this wild creature, the woman with many names, still hasn’t made you hers.

ENDYMION

Stranger, I am hers.

STRANGER

I meant to say ... Haven’t you heard the story about her and the shepherd, who was ripped apart by dogs for his indiscretion ... the man-stag?

ENDYMION

I know everything about her, stranger. Because we have talked and talked while I pretend to sleep. It’s like that every night, and I haven’t touched her, the way you wouldn’t touch a lioness or the green water in a pond, or that which is more yours than anything and holds your heart. Listen. She stands before me—this thin, unsmiling girl—and she watches me. Her vast, transparent eyes have seen so much. Still see. Possessing with those eyes. There’s a berry in her eyes and there’s the beast, there is screaming and death, the cruel entreaty.

I know this bloodshed, this torn flesh, the ravenous earth, the solitude. For her, savage goddess, this is solitude. For her, the beast is solitude. She touches me the way one would pet a dog or feel the trunk of a tree. But she watches me. This thin girl in a short tunic, so much like any girl you’d see in your own village.

STRANGER

Endymion, haven’t you told her anything about your life as a man?

ENDYMION

Stranger, you know such dreadful things and yet you don’t know that the savage and the divine cancel out the man?

STRANGER

I know that when you go up Latmus you stop being mortal. But immortals know how to be alone. And you dislike solitude. You look for sex in beasts. You pretend to sleep when she’s there. What exactly have you asked of her?

ENDYMION

If she would only smile again.

I would bleed for her, be the flesh in her dog’s mouth.

STRANGER

And how does she answer?

ENDYMION

She says nothing. She watches me. She leaves me alone at dawn. And I search for her among the trees. The daylight hurts my eyes. ‘You should never wake up,’ she tells me.

STRANGER

Mortal man, the day you are truly awake is the day you will know why she’s protected you from her smile.

ENDYMION

I already know, stranger, Stranger who talks like a god.

STRANGER

The earth is crowned by both the divine and the awful, and we walk these roads. You’ve been saying that very thing.

ENDYMION

Oh itinerate god, her tenderness is like dawn, it is the earth and sky revealed. It is divinity. But toward the others, the things and beasts—the savage has a brusque laugh and a vicious rule. No one has ever touched her knee.

STRANGER

Endymion, let your mortal heart settle. Neither god nor man has touched it. Her raspy, motherly voice is everything and all that savage can ever give you.

ENDYMION

And yet.

STRANGER

And yet?

ENDYMION

As long as the mountain is there, I will not sleep in peace.

STRANGER

Everyone has their own kind of sleep, Endymion. Your sleep is a plethora of voices, cries, of earth, sky, days. Sleep with courage, you have nothing else worthwhile. Savage solitude is yours. Love her like she loves. And now, Endymion, I must leave you. You will see her tonight.

ENDYMION

Thank you, itinerant god.

STRANGER

Farewell. And remember, you must never again wake up.

Theseus, Postcard, Detail

(British Museum).

(British Museum).

BULL LELEGO & THESEUS

forgot to lower the black sails on his ship, signaling his death.

Grief-stricken, Theseus’s father threw himself into the sea, leaving

the kingdom as inheritance. This is very Greek, as Greek as the

repulsion for any sort of mystical monster cult.

LELEGO

The hill over there, that’s home, sir.

THESEUS

There isn’t any bit of land on the horizon that in this dusky light doesn’t seem like our old hill.

LELEGO

We once toasted the sunset over Mount Ida too.

THESEUS

It’s nice to come home and nice to leave. We should drink more, Lelego. We’ll drink to the past. The greatness of everything left behind and everything rediscovered.

LELEGO

The whole time we were on that island, you never talked about home. You had no regrets about what we left behind. You lived in the moment. Then I watched you leave, the same way you’d left home, without looking back. Will you be thinking of the past tonight?

THESEUS

We’re alive, and we have this wine and the shores of home ahead of us. There are many things a person might consider on a night like this—even if by tomorrow wine and home shores won’t be enough.

LELEGO

What are you frightened of ? It’s almost as if you don’t believe in your own return. Why don’t we take down the black sails and dress the ship white? You promised your father.

THESEUS

We have time, Lelego. Time tomorrow. I like these sails fluttering over my head, they’re the same ones we flew when we were heading into danger, and none of you knew if you’d ever come back.

LELEGO

But, you knew, Theseus?

THESEUS

More or less ... My hatchet never fails.

LELEGO

Why do you hesitate?

THESEUS

I’m not hesitating. I’m thinking about the people I ignored, the great mountain and who we were back on the island. I’m thinking of our last days in the kingdom, that palace with endless courtyards, and how the soldiers called me the Bull King. Remember? You become what you’ve killed on that island. I was starting to understand them. Then they told us about the grottos of the gods in the forests of Ida, where gods were born and died. Don’t you get it, Lelego? They killed gods like they were animals on that island. And, if you kill a god, you become a god. Then we tried to climb Ida ...

LELEGO

Being away from home makes you brave.

THESEUS

They spoke of such amazing things. The women, those tall, blonde women who spent the mornings sunbathing on the palace terraces and then would climb up to the groves on Ida where they’d hug the trees and the animals.

Sometimes they stayed there.

LELEGO

The women are the only brave ones on that island. You know that, Theseus.

THESEUS

There’s one thing I know. I prefer women to be at their looms.

LELEGO

But there aren’t any looms on the island. Everything is bought overseas.

So, what are the women supposed to be doing?

THESEUS

Not growing old in the sun thinking about gods. Not trying to find divinity in tree trunks or the ocean. Not chasing bulls. I used to think it was the fathers’ fault, those clever merchants who dressed like women and liked to watch boys twirl around on bulls. But that’s not it, or not only it. They have different blood. There was a time when Mount Ida was only for goddesses. One goddess. She was the sun, the trees, the sea. Men and gods alike turned into fools in her presence. When a woman escapes a man, and finds herself in the sun and among animals, it’s not the man’s fault. The blood gets damaged; it’s chaos.

LELEGO

Only you could say that. Are you thinking of the foreign woman?

THESEUS

Her too.

LELEGO

You’re the captain, and whatever you do is right by us ...

Though she gave us the impression of being docile and obedient.

THESEUS

Too docile, Lelego. Docile like grass or the sea. You look at her and see she’s pliant, and she can’t feel you. Like the groves on Ida, where you move forward with one hand on your hatchet, but then the silence becomes overwhelming and you have to stop. Like the panting of an animal lying in wait. Even the sun and air seem to be part of the ambush. You don’t fight the great Goddess. You don’t fight the earth ... or its silence.

LELEGO

I know all this as well as you. But the foreigner led you out of the labyrinth. She left her home. Which has nothing to do with hot blood or damaged blood. She left her own gods behind to follow you.

THESEUS

But the gods didn’t leave her.

LELEGO

You also said they slaughter them up on Ida.

THESEUS

Then the killer becomes the new god. Look Lelego, you can kill bulls and gods in a cave, but you can’t kill the divinity in their blood. Ariadne had island blood too. I know it like I know the bull.

LELEGO

You were cruel, Theseus.

What do you think she said when she woke up, miserable?

THESEUS

I know. Maybe she cried out. But for nothing. Invoked her country, the homes, and her gods. She’s got the sun and the earth. Us foreigners are nothing to her now.

LELEGO

She was beautiful, sir. She was like the earth and sun.

THESEUS

And we’re only men. I’m sure they’ll send someone over to console her, some god in pain, some gentle and shadowy god, who’s already tasted death and is tied to the apron strings of the great Goddess. Will it be a tree, a horse, a ram? Maybe a lake or a cloud? Anything goes in her sea.

LELEGO

I don’t know. Sometimes you talk like a child playing a game. You’re in charge so we listen to you. Other times, you’re old and cruel. One might say that some part of the island got into you.

THESEUS

That’s also possible. If you kill it, you become it. You don’t think it, but we’re coming from far away.

LELEGO

You’re not even warmed by the wine of our homeland?

THESEUS

We aren’t home yet.

*

*

*

Order direct from

Archipelago Books

here.

Cesare Pavese (1908–1950) was born in the countryside of northern Italy. He translated Joyce, Melville, and Gertrude Stein for Italian readers, and worked as an editor at the publisher Einaudi, where he brought about the publication of Freud, Durkheim, and Jung. Pavese’s first poetry collection was published in 1936, followed by a spate of novels. In 1950, Pavese’s novel The Moon and the Bonfires won the Strega Prize. Later the same year, he committed suicide. Alongside his poems and novels, Pavese has been celebrated for essays on American literature and his diaries.

Archipelago Books

here.

Cesare Pavese (1908–1950) was born in the countryside of northern Italy. He translated Joyce, Melville, and Gertrude Stein for Italian readers, and worked as an editor at the publisher Einaudi, where he brought about the publication of Freud, Durkheim, and Jung. Pavese’s first poetry collection was published in 1936, followed by a spate of novels. In 1950, Pavese’s novel The Moon and the Bonfires won the Strega Prize. Later the same year, he committed suicide. Alongside his poems and novels, Pavese has been celebrated for essays on American literature and his diaries.

Minna Zallman Proctor is the author of Landslide: True Stories, Do You Hear What I Hear? (Catapult, 2017) and co-author—with Bethany Beardslee—of I Sang the Unsingable: My Life in Twentieth Century Music (University of Rochester Press, 2017). Her stories, essays, and book reviews have appeared in Bookforum, Conjunctions, The Nation, and The New York Times Book Review, among other publications. In addition to The Leucothea Dialogues, recent translations include These Possible Lives (W.W. Norton & Co, 2017) by Fleur Jaeggy and Happiness, As Such (Daunt Books, 2019) by Natalia Ginzburg.