Rehearsal / 52. William Weller

![]()

Holloway Motel 1518 North La Brea

Los Angeles CA 90028 (circa 1960)

A man’s heart plans his way, but the Lord directs his steps

Proverbs 16 : 9

Holloway Motel 1518 North La Brea

Los Angeles CA 90028 (circa 1960)

A man’s heart plans his way, but the Lord directs his steps

Proverbs 16 : 9

DUSTY JADE A short story.

Chapter 1 Carmen was deep into her evening prayer ritual when the phone rang. She usually took it off the hook for her hour of sanctity, however she’d called her friend Alex earlier, and he was going to call her back about picking up some things for the church flea market on Saturday. She answered, but it was her father saying that her mother’s viewing would be tomorrow from eleven to noon at the Crestmore Funeral Parlor. He added that he might not be able to meet her there, nor was he sure if her brother Jason would be in attendance either. She was disappointed, but not surprised.

The next morning, she made the twenty-minute drive to a suburb on the outskirts of L.A. She parked her Ford sedan behind the mortuary building, made a quick survey of the surrounding bleak landscape, and exclaimed to herself, ‘I thought they wanted Forest Lawn.’ This was definitely not Forest Lawn. It was a beige single-story stucco complex, with an overhanging portico shielding the entrance. As she approached a young man with a press sticker on his hat blocked her way.

‘Hello. Are you not the daughter of Carolyn Delmonico?’

‘Who wants to know?’

‘Wilber Haynes, I’m the entertainment reporter for the Herald Examiner. I’d like to ask you a few questions?”

‘I’m here to pay my respects, so I’d rather be left alone, if you don’t mind.’

‘Were you there when it happened?’

‘I can’t talk now, and besides, it doesn’t matter.’

‘I’m sorry. Here’s my card in case you want to talk.’

After taking his card, she pushed past him, then went through the entrance double doors, registered at the desk, and was led by an attendant to the viewing room where her mother lay in state.

She knelt beside the casket, not wanting to see the mask of her mother’s embalmed and waxen flesh. No life there obviously, and she felt no grief, only a twinge of regret. A wand of sunlight from a narrow high window shone in the room, striking the foot of the casket, illuminating the brightly painted toenails sticking out of the white pumps. Carmen looked to the ceiling and made a prayer steeple with her hands. When the funeral home attendant saw this solemn gesture, he left the room saying he would leave her alone for a while. As soon as he was gone she found enough courage to look at her mother’s face. She saw that her mom was wearing the jade necklace that Alex had given her! It didn’t belong to her. Why was she wearing it?

She put her hands behind her mother’s neck and undid the clasp of the necklace. It quickly disappeared into her purse. She crossed herself, stepped back and let out a low moan of pain, which was overheard by the attendant who reappeared.

‘Excuse me miss, are you all right?’

‘I’m OK, it’s just that she looks so peaceful now. And you made her look beautiful.’

‘I’ll pass your compliment on to the crew. I don’t usually pay much attention to them after they’ve been embalmed. I see so many, and my work is done by the time they’re in the box.’

Carmen could only offer a soulful ‘Oh’ in response, then ‘I have to get some fresh air.’

She left through the front entrance, and wandered around the dusty parking lot of the mortuary, which was set on the edge of town and bordered by a low hill dotted with chaparral. Midday. Hot. What a dismal place to end up, she thought, especially for someone of her family’s stature and means. Had her father lost everything?

There was a footpath at the far edge of the lot, which she took, climbing to the top of the hill. From the ridge she could see the ocean and downtown. She turned the necklace over and over in her hands, before throwing it into a clump of sage, then realized her fingerprints were on it. She could see its silver clasp in a clump of thick brush. After retrieving it, she rubbed it with powdery earth before throwing it as far as she could so that if someone found it they wouldn’t connect it to the path she’d taken. She was pretty sure that no one had seen her go up there anyway. Back at her car she dusted off her shoes with a scarf she’d left in the back seat with some other stuff she hadn’t bothered to deal with like the child’s chair that she was going to take to the goodwill. Donating her possessions was a satisfying penance, but not something that would absolve her of the sin she had just committed. It occurred to her that maybe she should go back inside the building, and make amends to her mother’s body, but as she was crouching down lacing her shoes, she saw a black Lincoln pull up to the entrance. She watched furtively as her parent’s friends, the Conroys, parked the car. They hadn’t seen her, so she started the car and drove away.

Soon she was home in her third-floor apartment, relieved to be away from the outside world. She knelt before her homemade altar, a coffee table covered with a scarf and three votive candles in their glass cups. She would have liked to have burned some incense, but the apartment manager didn’t like the smell, afraid that one of the tenants might be trying to hide marijuana fumes.

The apartment, a one room studio, wasn’t fancy, but all she could afford on the meager stipend she got from her rich older brother, a movie producer who hired her to read scripts, the ones that would never be produced. Her spiritual obsessions weren’t employable, and her fear of authority made it difficult for her to face the mean giants who might give her work. Her only social outlet was church, though she rarely attended Sunday services. She went mostly to weekday Mass where she didn’t have to mingle with others. The apartment was a sanctuary which she didn’t have to leave except to buy groceries. Her obsessive attraction to religious magic left her feeling languid. She didn’t care about being famous like everyone else she knew, and she wasn’t sad, because her faith brought her peace and good spirits unless she had to deal with the trivialities of daily life or the death of a parent who hated her.

Her father was planning a memorial, but he was a wreck so it might not happen, which was fine with her since she wouldn’t have to talk to anyone in that phony polite tone of voice that her mother’s friends used. When he called her and brought her to the house to tell her the news, he left her there saying that he was going to sell it, and she should take the personal items she wanted. The only thing she could think of was the jade necklace. She’d rummaged through the house, but couldn’t find it. Instead, from the medicine cabinet she took a bottle of Seconal and a box of lozenges marked ‘for future use only.’ She had no idea what they were. Probably her mother’s guru, the swami, had brought them for one of the séances they held at the house occasionally. The rites had something to do with not drinking so much, but obviously didn’t work because her mother got drunk and tripped over a sprinkler, hitting her head on one of the massive stone urns that lined the terrace. She didn’t deserve that necklace! Jade was sacred and it was blasphemous to kill oneself with drink, and now she had to do penance for her, praying and living an honorable monastic life.

Had she taken the necklace from her mother’s corpse as it lay in state? She had. It wasn’t worth much in money, just a string of silver mounted jade, modest for someone so important.

The morning of the viewing she had gone to an early mass, then home, where she prayed and prayed again, which didn’t help when later she was put on the spot by the reporter on her way into the funeral home, asking her those silly questions about her mother. He didn’t respect her privacy and it was upsetting. Talking about her wasn’t going to help. Maybe the Seconal would? Tonight would be a good time to take a couple, especially after having to look at a dead body laid out in a coffin in a room lined with dark red curtains.

But first, she watered her potted plants then closed the Venetian blinds and dimmed the lights to the level of invisibility. Maybe her Spartan décor would save her from damnation. Hadn’t she survived her parent’s barstool dungeon and the glowing chandeliers? Her mother’s twenty-four-hour sunglass wearing—well, maybe not while sleeping. Or the aquarium with the fighting fish papa loved, their effeminate flowing fins, orangey pink and vicious.

She knelt before her shrine, which now seemed lacking compared to the lavish display at the morgue. No, it wasn’t a morgue, it was a funeral home. She wished she’d taken some flowers from the viewing room instead of the necklace, but that might have been too obvious. The attendant surely would have said something about them being provided by the facility, and not donations from friends and relatives.

She downed three of the red and white pills with a coke, waited a few moments then chewed the lozenge, which tasted faintly metallic, zinc perhaps. Something about it reminded her of the garden shed in the backyard of her parent’s house, where they kept the garden tools and the barbecue, and how no one ever used the flagstone terrace, which was always too hot or too cold. On the few occasions when Carmen had her own friends over to play, they would stack the lawn chairs into a tower shaped thing that was higher than they could reach unless Javier, the gardener, helped them. When their structure was finished they snuck up to the second story playroom to see if their work was attracting any attention from the grownups, but that never happened because Javier took it down before anyone came out of the drinking room. Leaving the bar would mean carrying the cocktails and the possibility that they might trip and spill one, and besides it was much cozier inside with talk of the shared misery of a life of competition and prosperity. At least they weren’t on heroin like Judy’s dad, though maybe he wasn’t so garrulous and bombastic like her parent’s friends.

Sometimes Carmen would hide out in the laundry room, just to see if somebody would miss her. She did this until the day she crawled into the dryer and pulled the door shut on herself. She didn’t panic, because she knew Alva, the maid, would make the rounds of the house looking for a place to sneak a cigarette. The dryer was still warm and it smelled of fabric softener. Her parents were rich so it was a large machine. She liked the womb-like warmth curled in the fetal position. But that day Alva wasn’t showing, instead her mom shuffled in calling her name. Carmen knocked several times on the glass door of the drum, now contrite. Carolyn Shutters ignored her, put the temperature dial to cool and turned it on. She felt herself fall on the first revolution, then hung on to one of the ribs.

Her mother stopped the dryer and opened the door. Carmen slithered out dazed, sprawled slug-like on the floor.

‘Eleanor Conroy is visiting, and she’d like to say hello to you before she leaves. You remember Eleanor, don’t you?’

She then bent down and pulled the child to her feet. Carmen recalled the incident as if she were reading a description of it in a book. Maybe the Seconal had kicked in? Anyway, she didn’t care much for Eleanor so it didn’t matter. The memory made her resolve to buy a scented candle that would blot out the smell of the building’s communal laundry facility. Everyone used fabric softener now. Her mother was one of the first.

The candles on her altar had gone out. When she tried to relight them, the match sputtered, so she stretched out on the sofa, out of the mood for her prayer ritual, and too tired to pull down the Murphy bed.

The next morning she woke up to a thumping sound outside her window, a relentless bass tone. On opening the blinds she saw what looked like a huge metal flying fish without fins, or some kind of insect, a dragonfly. So it was a sin to take the necklace. God had sent a machine to shame her for what she’d done. The thing spun around a few times and flew away.

She went to her radio, which was always tuned to the classical music station, but now she heard people talking in Spanish. She turned the dial, and an evangelist came through screaming about sin in a booming baritone voice.

‘Redemption possible only if one chose...’

She changed the station again, this time to a show with people talking, but their words so sounded like gibberish to her. She snapped it off, looked out the window again, stared at the infernal machine that had circled back and brought sirens with it. Maybe the Japanese were invading?

She picked up the phone expecting to hear an operator ask ‘Number please,’ instead she heard an electronic sound. ‘Help,’ she said into the receiver. No response, only an irritating peeping. She hung up, lit the altar candle, and knelt down to pray. The street outside was suddenly quiet until the silence was broken by a rhythmic bass beat coming from a loudspeaker somewhere in the neighborhood. She didn’t know this music. It throbbed with a blatant sexual pulse, driving sensually to perdition.

She thought about the reporter again. What an obnoxious twerp, but cute. She wanted to go out and buy a morning paper, but the possibility of the flying machine deterred her. Would there be something about this in the news? Maybe her friend Alex would bring her one. He lived only a few doors down the street. She picked up the phone to call, but there was still no operator, only a dull tone. Perhaps the machine had cut the phone lines? Her lights were still working. Should she go back and try to find the necklace? Would that correct the horror of what was happening? She realized now that she wasn’t a saint, only a selfish, disrespectful daughter.

She summoned the courage to look out her window, and saw that nothing was the same as it was the day before. The trees had all grown, and there were new apartment buildings everywhere. The street was jammed with sleek, odd looking cars going to work, or were they leaving town to escape the invasion? The radio was no help, and since there was no classical music she was lost.

She looked at the box of lozenges. ‘Proverbs 16 : 9’ was written clearly on the label. It was one she didn’t know, and she didn’t feel like looking for it in her Bible, so she returned to the sanctuary of the altar, where she sat motionless in a childlike pose before realizing that she should look after her car. She had parked it down the street in her rush to get home, not bothering to pull into the underground parking garage of the building where she might not have found a space.

She went out into the hallway, not locking the door, then slowly made her way down the stairs to the lobby, which was empty now, no reception desk with smartass clerks, only a wall of mailboxes and two overstuffed chairs. Once she was on the sidewalk she found her car intact, but surrounded by ones of designs she didn’t recognize, painted bright colors. As she stood gaping at the scene, two young men walked by, one of them commenting, ‘Wow, look at that, a 1940 Ford in perfect condition.’

The car was okay, and since she hadn’t eaten breakfast or had coffee, she went back up the stairs. In the hallway leading to her room she saw two persons coming out of her apartment. One of them said ‘Fifteen hundred not including utilities.’ The other one said, ‘I’ll take it.’ Carmen passed them in the hall, but they seemed not see her. It was as if she passed right through them. The door was still unlocked, and when she stepped inside she saw that the place was completely empty of any furnishings. The kitchen was sparkling clean, with a shiny new icebox that had light inside and no food. She wondered what happened to all her stuff, but she was starving, so thought to go to the corner café, which she hated, and visited only in emergencies like this. It was now something called a Starbucks. She waited in line to buy a coffee and a pastry.

What is a ‘latte?’ she asked the clerk.

He stared at her for a moment before replying disdainfully. ‘It’s coffee with heated foamed milk.’

She had never heard of latte or foamed milk, but she ordered one anyway, and was pleasantly surprised how good it tasted.

Chapter 2 After Starbucks she went back to the apartment. The front door to the building was locked, which was unusual, so she rummaged through her purse for the key. When she found it, it didn’t fit the lock. Then she noticed a little box with a grid of buttons beside the door. She tapped it a few times, but nothing happened until a young woman came up the steps and said,

‘You forgot your code? Here, let me.’ She punched in some numbers, and the door opened. Carmen followed her in.

‘Oh, thank you. I’m in room 315, but they changed the lock, I guess?’

By the time she’d said this, the girl was already in the elevator. Carmen hung out in the lobby for a while, marveling at the new setup. She didn’t bother trying to open her mailbox, because she never wrote letters and her brother took care of the bills. The hallways were perfectly clean, and there was no fabric softener in the air.

After taking the stairs to the third floor, she walked the length of the long hall and tried to open the door to her room. It was locked too, something she often neglected to do. After fumbling in her purse again, she finally found her key. It unlocked the door, a miracle. When she surveyed the room, she saw what looked like her mother’s boudoir, with the chic décor and the modern furniture she hated. Gone was the dark green paint on the walls and the wainscoting. Now everything was painted a light gray tone. Her coffee table altar had been replaced by an oval piece of thick glass on spindly chrome legs. The sofa was the same color as the walls, and a big stainless-steel ball on pole drooped over one end. ‘Someone hired Pierre, my mother’s decorator!’ She screamed because the slick and minimal design her mother loved was in her apartment now. In the kitchen her basket of fruit was now a glass cylinder on a metal base. The sink was sparkling clean, and the refrigerator had only soymilk and yogurt.

She tried the phone again with the same result. The dial had been replaced a square of buttons. On her desk was shiny rectangle with a typewriter keyboard. When she touched one of the keys the thing bloomed brightly, then an image of a mountain range dotted with little blue squares appeared. Near the keyboard was a blob of white plastic. She moved it and saw that a little arrow scurried around the screen. When she tried it again, one of the squares became a page of typing and letters. It was the front page of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, which read, ‘EXTRA—edition March 11, 1943—BREAKING NEWS—Carolyn Delmonico, wife of Hollywood producer Damon Delmonico, dies in a freak and suspicious garden statue incident.’ There was a picture of her mother wearing the jade necklace.

Carmen wanted to collect herself after seeing these things she’d never seen before, so she went to open the blinds and look out the window, but the Venetian blinds weren’t there. In their place were diaphanous white curtains. She pulled them open, and saw that the mechanical dragonfly was hovering over a nearby intersection. Red lights were blinking everywhere. She felt faint, stretched out on the horrible sofa, and fell asleep.

When she woke up, there was a young man standing in the middle of the room, someone who looked like Wilbur Haynes from the newspaper. She sat straight up and yelled, ‘I can’t give you an interview right now, whoever you are. I’m really upset.’

‘Excuse me miss, but I just rented this apartment. What are you doing on my sofa?’

‘Nothing, but I think I’m in my mother’s bedroom.’

‘Not as far as I’m concerned. And besides, you’re trespassing.’

‘But this was my place before, and now all my things are gone; my altar, my candles, the reliquary.’

‘Excuse me? Your altar, are you some holy figure who’s come here to convert me?’

‘I’m not holy, I’ve committed a horrible sin.’

He gave her an admiring once over, and said, ‘Well, whoever you are you should probably leave. I don’t use escort services.’

‘I’m not an escort, whatever that is, I live here. I have the key. How do you think I got in? Go ahead, call the

authorities. I have proof.’

He then noticed his computer was open. ‘Hey, have you been going through my files?’

‘I just touched it and it came to life somehow. What is it?’

‘You don’t know what a computer is? Where in the hell are you from, anyway?’

‘It seems I’m in hell. She did this, my mother.’

‘Your mother?’

‘Yes.’ She got off the sofa and stood next to him at the computer, pointing to the screen. ‘There she is. That’s her, Carolyn Delmonico. Why is her picture on your machine?’

‘It’s not a machine. I’m doing research for a book I’m writing about life in L.A. in the 1940s.’

‘I was there.’

‘That’s your mom? You look a lot like her.’

‘Don’t say that. She was really mean, and now she’s getting her revenge.’

‘Well, since you claim to have been there when it happened, maybe you can tell me more?’

‘To some, she was very charming, but to me she was rather cruel. She took my necklace.’

‘Oh, one report I read said that a valuable necklace was stolen from her body while she was at the mortuary, and it was suspected that the daughter took it. It was never found.’

‘I might know where it is, but first, tell me how you afford this place with all the fancy fittings?’

‘I’m an influencer for modern apartment design.’ He took out his phone.

‘See here it is on TikTok.’ He showed her the screen of the phone.

‘What is that thing?’

‘It’s my phone. It’s harmless. Don’t worry.’

‘I don’t see anything, just a piece of glass.’

‘You can’t see the image? It’s the room here.’ He held it closer to her.

‘I need glasses, maybe?’

‘If you were here in the 1940’s then you must be a ghost?’

‘I can’t be, because I didn’t die. After I came back from the funeral home I was so disturbed that I took a couple of the Seconals I got from her medicine cabinet, and went to sleep. This is what I saw when I woke up.’

‘Wow, Seconal is a really strong drug.’

‘I don’t usually do stuff like that because I’m in a strict religious program, but after I saw her body, and she

was wearing my...’

‘Wearing your what?’

‘Oh nothing, she was lying there dead, and it made me feel so bad that I had to drive home and pray, but it didn’t help so I... Oh, really need the bathroom now. I think I might throw up.’

Wilbur snapped the computer off as she went in, and when she came out he pointed the piece of glass at her. It made a clicking sound like the shutter of a camera.

‘It’s OK. I didn’t vomit in your sink. Go ahead, take a look.’

‘I guess ghosts don’t vomit?’

‘I can’t stay here. I want my home to be the way it was before.’ Carmen waved to him as she left the apartment, and went into the hallway. Wilbur yelled, ‘Wait!’ but she ran down the hall out of sight.

Chapter 3 She got to her car, started it, thought, ‘Thank goodness this still works,’ then looked at the gas gauge, which showed almost empty. The nearest station was only a few blocks away. Once there she saw that it wasn’t the same either. Cars lined up, stopped next to some big boxes shaped like coffins. Customers stuck what looked like playing cards into them and pumped the gas themselves. No attendants arrived to do that and wash the windows.

She pulled up to one of the boxes, got out of the car and stared at the illuminated screen that asked for her zip code. ‘For heaven’s sake, what is a zip code?’ She sat in the car again and sulked until the car behind her honked a few times. Then a bearded young man, wearing a sleeveless shirt that showed his tattooed arms, approached her rolled down window and asked, ‘Is there a problem here?’

‘I don’t know what to do. No one is coming to help me.’

‘This station is self-serve only, but I can help you. Are you paying with cash or by credit card?’

Not knowing what a credit card was, she said ‘Cash.’

‘Then you have to pay inside. Where are you from, anyway?’

‘I live just down the street. I’m just not used to all these new things.’

‘Really? This really isn’t exactly new technology.’ He went back to his car and moved on to another pump. Carmen went into station office and asked the station attendant, ‘How much does a tank of gas cost here. ‘That’s your car, the Ford?’ Carmen nodded. Yes. ‘Let’s see, a car like yours probably holds twenty gallons, so at three forty-nine a gallon, that is around seventy dollars.’

‘I’ll take half a tank.’

She was aghast at the cost of thirty-five dollars for a half tank of gas, but she had some inheritance cash in her purse, and handed him a couple of twenties. With the change she bought a big bottle of Coke, a brand she knew, and a bag of Fritos, which was one she’d never heard of.

Back at the pump she was able to get the gas in her car with the help of an older man wearing a baseball cap and a Hawaiian shirt, who had been waiting patiently in a fancy car behind her. He could have pulled around to another pump, but he was curious about this beautiful young creature wearing a long out of fashion shirtwaist dress, and someone who didn’t know about modern gas stations. He pumped the gas for her, and when the nozzle was back in its slot he said, ‘Say, this is a nice old Ford, and you’re wearing a dress from the time it was in fashion. Are you working in a period movie or something like it?’

‘I don’t know what that is, but thanks for your help.’

‘I’m a producer, so if you ever want a part in a film, here’s my card.’

‘My dad was a producer.’

‘Oh yeah, what’s his name.’

‘Damon Delmonico.’

‘Oh my, he was famous in the 40’s, or infamous is a better word. It was quite a story at the time. They never really found out who did it.’

‘And I hope they never do.’ With that she drove away, thinking maybe she was in her own movie as she turned right onto 6th Street which was near her old church. It was too late for morning mass, but at least she could pray and be safe from where ever she was. It was a relief for her to see that all inside was the same; the pews, the stained-glass windows, the altar and someone practicing a Bach fugue on the organ. She sat in one of the last rows of pews and bowed her head. Finally, she was somewhere besides the modern Hell around her.

When she left the church, she was hungry and drove to the diner she knew on 3rd, but it had been replaced by a drive-thru hamburger place. She ordered a chicken sandwich, fries and a chocolate milkshake. Feeling better now with a full stomach she headed in the direction of her parent’s house, then panicked at the thought of seeing it. Her dad wouldn’t be there, and she didn’t want to see him anyway, so she went back to her old apartment, parked the car and waited on the steps until somebody went in or came out. When someone opened the door, she told them she was in room 315, and that she lost her key so they let her slip by.

Chapter 4 She used her key and let herself in to her apartment without knocking, and found to her surprise that all was the same as it always was, with her altar, green paint on the walls and black rotary dial telephone. The AM radio was playing soft classical music. She sat at the altar and lit the candles with matches that worked.

‘Thank you, dear Lord for bringing back my home.’

She closed her eyes in silent prayer as her corporal form slowly disappeared, which she didn’t realise until after her long reverie that she might need to use the bathroom, but couldn’t see herself in the mirror. And she was exhausted. She tried to pull out the Murphy bed, but it wouldn’t budge, because she was only mind now, and had no muscle strength. She could pass through the wall and go into the kitchen if she wanted to though. She went back to the sofa and willed herself to make it feel solid enough for her to lie down and sleep. She didn’t need much sleep anyway.

When awake again she saw men coming into the room. They began to remove the furniture. Her sofa was soon gone and she was left hovering where it once was. She stood up. One man passed right through her. At least she felt rested, as she walked around her empty room.

She thought to go look after her car, but when she stepped onto the porch of the building she wasn’t able to go down the stairs because where there was sun, there was an impenetrable wall that she couldn’t pass through. In the shade she was OK. This didn’t bother her, since without flesh, her mind was at rest. And besides, she couldn’t really do any of the things out there she used to do. She couldn’t drive her car or shop for food. She didn’t need to eat either. From the porch she made herself appear in the apartment, and by the time she did this, a crew of workers had torn out the wainscoting and painted the walls an off-white

colour. She knew then that her sense of time wasn’t the same as that of people in the real world. She thought she’d been gone only a few minutes when she went to look for her car.

Her old furnishings were gone. She missed them, but also had a feeling of peace and no worry about the future. In her new state of being she liked roaming around the room, or looking out the window at the snarled traffic on the boulevards. She amused herself by going in small spaces, the refrigerator for instance, though if anyone could see her they would see her legs sticking out the side. And when she needed to sleep the bathtub was nice. She was sleeping a lot even though she had no physical body, and she didn’t

have much else to do.

One day a young man carrying cardboard boxes into the room awakened her. He seemed to be in his mid-twenties, and he didn’t look like Wilbur from the Herald Examiner. He was a little scruffy and casual. Thank goodness for that. No more interviews about her mother. Soon he was joined by another young man, who helped him carry in a well-used sofa and a kitchen table with two vintage wooden chairs. They left. Then later, in the evening the scruffy one came back, and brought an electric piano that he set up on a spindly stand. He also brought a little black cube with a glass face, which he plugged in and placed on one the unpacked boxes. When he turned it on the glass lit up, and she could see images of people in black and white. It seemed to be a miniature version of a movie. The Murphy bed wasn’t there now. In its place was a narrow mattress on a long box.

‘So that’s where he’s going to sleep.’

Sometimes he played music on the piano, rhythmic pieces that were maybe even bluesy. She didn’t worry about her lack of privacy when he played because she felt less like her usual self, like another person entirely. If he turned off the movie sound when he played she would watch the flickering figures on the little screen and pretend to be his audience, silent and invisible. She got into that new person mood, which was more relaxed and even sensual. She’d never really had a boyfriend. Alex was just a friend. And there was too much guilt after sex. But now she liked seeing people hug and kiss in the mysterious little box. She was transfixed, but after staring at the screen for a long time, and seeing someone there who looked like her mother, she had a fever dream or maybe something more psychedelic. The shape of everything in the room got a little wavy with bright shimmering highlights. She staggered into the kitchen and crawled into the refrigerator until what she was seeing returned to normal. When he stopped playing she went back to the living room to see what he was doing. He sat looking at the box for a while, then got up, turned it off, and went into the bathroom where he brushed his teeth, used the toilet before finally crawling in his sparsely made bed.

The house was dark except for some light from the streetlights that made it through the flimsy curtains. It was a scene from one of the movies she’d been watching on the strange device, with heavy shadows and strong highlights in geometric shapes. She’d never seen a film noir.

She took her place on the sofa as if she were sitting in front of her altar. She could pray at least, since she couldn’t do much else except hang out in what was once her old place, and watch this person mope around when he wasn’t playing music or watching the movie box. She realised she missed the thing when he turned it off. It was all so very peaceful, and soon she went into a kind of reverie that allowed her to forgive her mother for the spinning dryer torture. But then what about her own theft of the necklace at the funeral home? It occurred to her that in another time Carolyn might have thought it funny if she had been around to see it. Maybe she saw her take it from above? Then time stopped, as it did when she tried to go outside and look for her car, and they cleaned out her apartment. But this time it was a short window of stasis, like a camera shutter going off. She felt as if she was being photographed at some formal event where her mother pushed her to appear before a group of strange people. She thought about how she had taken the Seconal, then the curtains stopped moving, and she thought she might be in a photo of a crime scene.

The next morning when he turned it on to watch with his morning coffee, she was there watching too, but instead of movies there were people at desks talking in front of boards with numbers or words that flopped up and down when a man in a suit pointed toward the display behind him. She was fascinated by the seemingly random activity happening on what looked like a painted piece of plywood with little doors. She could hear what the announcer was saying, but the words didn’t mean anything to her. What is a ‘vowel’ anyway? She thought of the vows she taken when she wanted to be a saint. Someone spun a big roulette wheel with numbers, then a woman would open one the doors revealing a letter, and after more letters a short phrase. ‘Time waits for no one,’ for instance.

Her roommate switched it off and left the apartment. For a fleetingly moment she missed seeing him, but she missed the shows she’d been watching with him more. She couldn’t turn the thing on, so she just sat there and stared at the curtain waving in a soft breeze filtering the sunlight. A peaceful and serene feeling came over her before the wind stopped, and the curtains didn’t move. The light slowly faded to total darkness. She felt blissful, and wished it would stay like it was so she could enjoy the vast emptiness of space and the twinkling stars.

Images

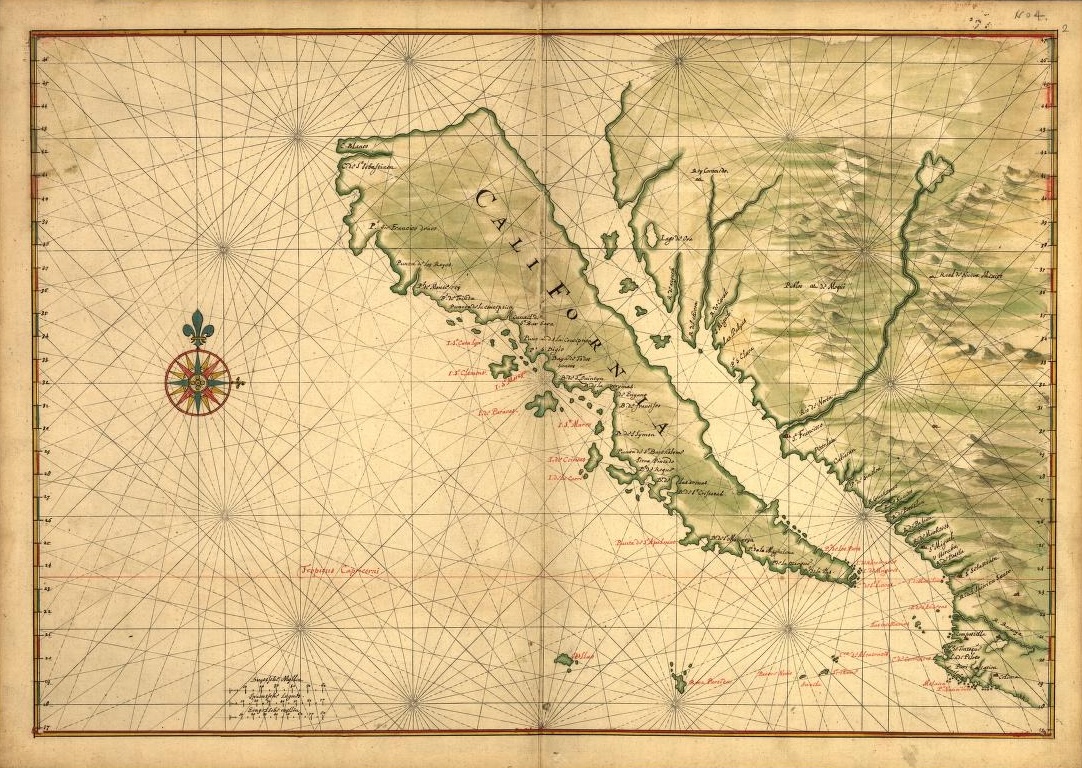

Top ‘California as an Island’ ... Throughout most of the seventeenth century, California was believed to be an island. The shown manuscript map of the Baja Peninsula—now the state of California—was drawn by Johannes Vingsboons for the Dutch West India Company in approximately 1639. Geography & Maps Division / The Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA).

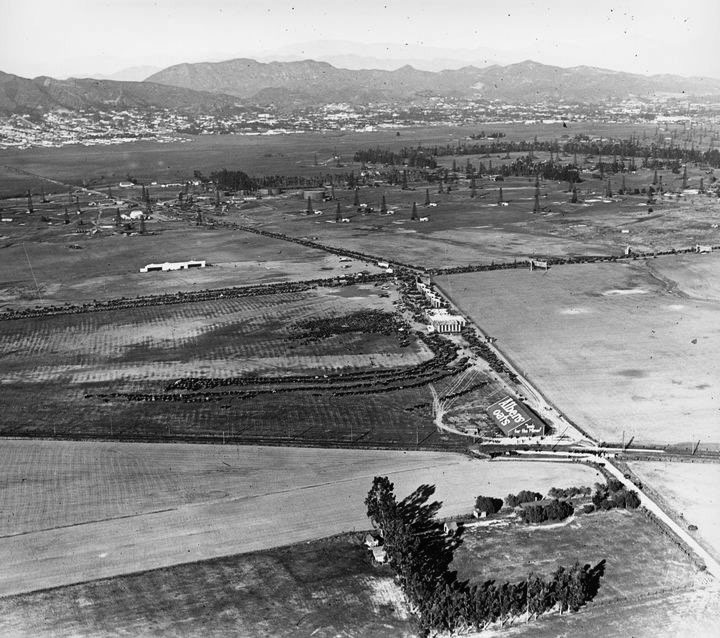

& Thereafter (1922) Aerial view looking northwesterly showing Crescent Ave (later Fairfax Ave) running diagonally from lower-left to centre-right, where it crosses Wilshire Boulevard (centre-right) and makes a slight bend north towards the Hollywood Hills. San Vicente runs diagonally from lower-right to upper left and turns up toward West Hollywood.

(1922) View looking north shows numerous cars parked on a lot (center of photo) near the airfield as well as along Wilshire Blvd. and Crescent Ave (Fairfax). Large sign on building in the lower-right center at the intersection of Fairfax and the San Vicente line of the Pacific Electric Railway reads, ‘ALBERS OATS.’

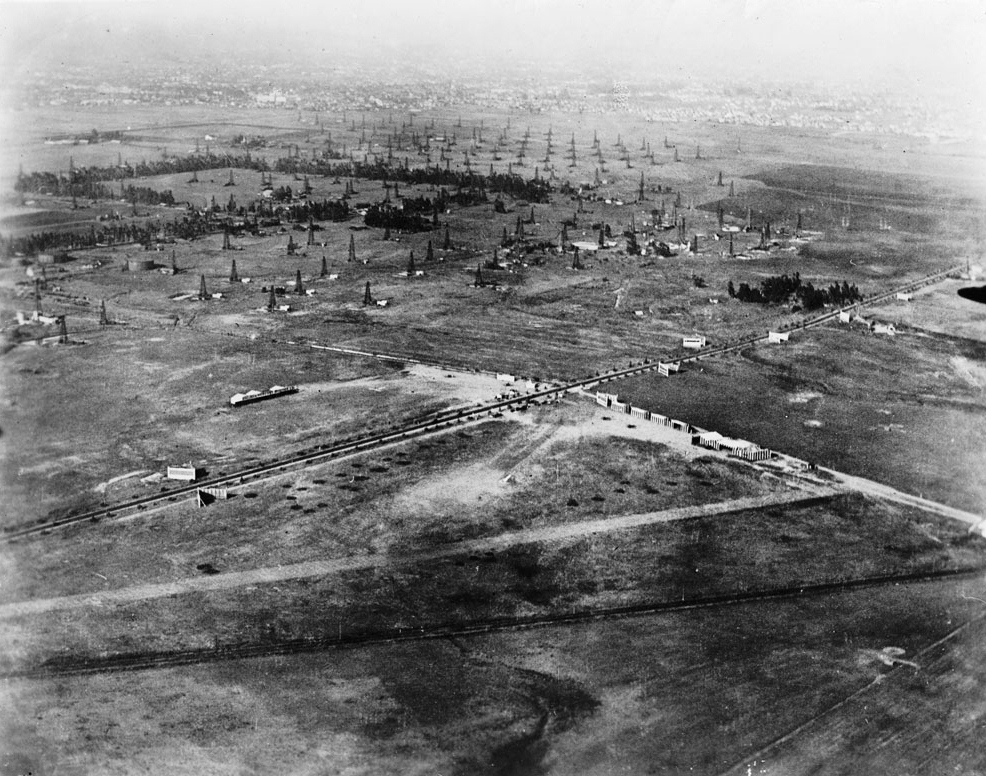

(1920) Aerial view of Crescent Avenue (now Fairfax) and Wilshire Boulevard in 1920 showing undeveloped land with many oil derricks. The tree-lined street is Wilshire. The diagonal line at the bottom is actually railroad tracks that would later become San Vicente Bouelvard. (℅ the Water & Power Associates—‘your gateway to Los Angeles’ water and power history’).

William Weller is a writer and artist living in Los Angeles. The city and its history inspires him, and he’s been able to work his nostalgia for earlier times as an apartment dweller and reader of crime fiction into his writing. This desire was furthered recently after seeing a book of photographs depicting the city in the 1950’s and 60’s before freeways and massive development.