Rehearsal / 18. Maarten Slof & Sam Wilson Fletcher

![]()

Pillar Mister (MMXXIII)

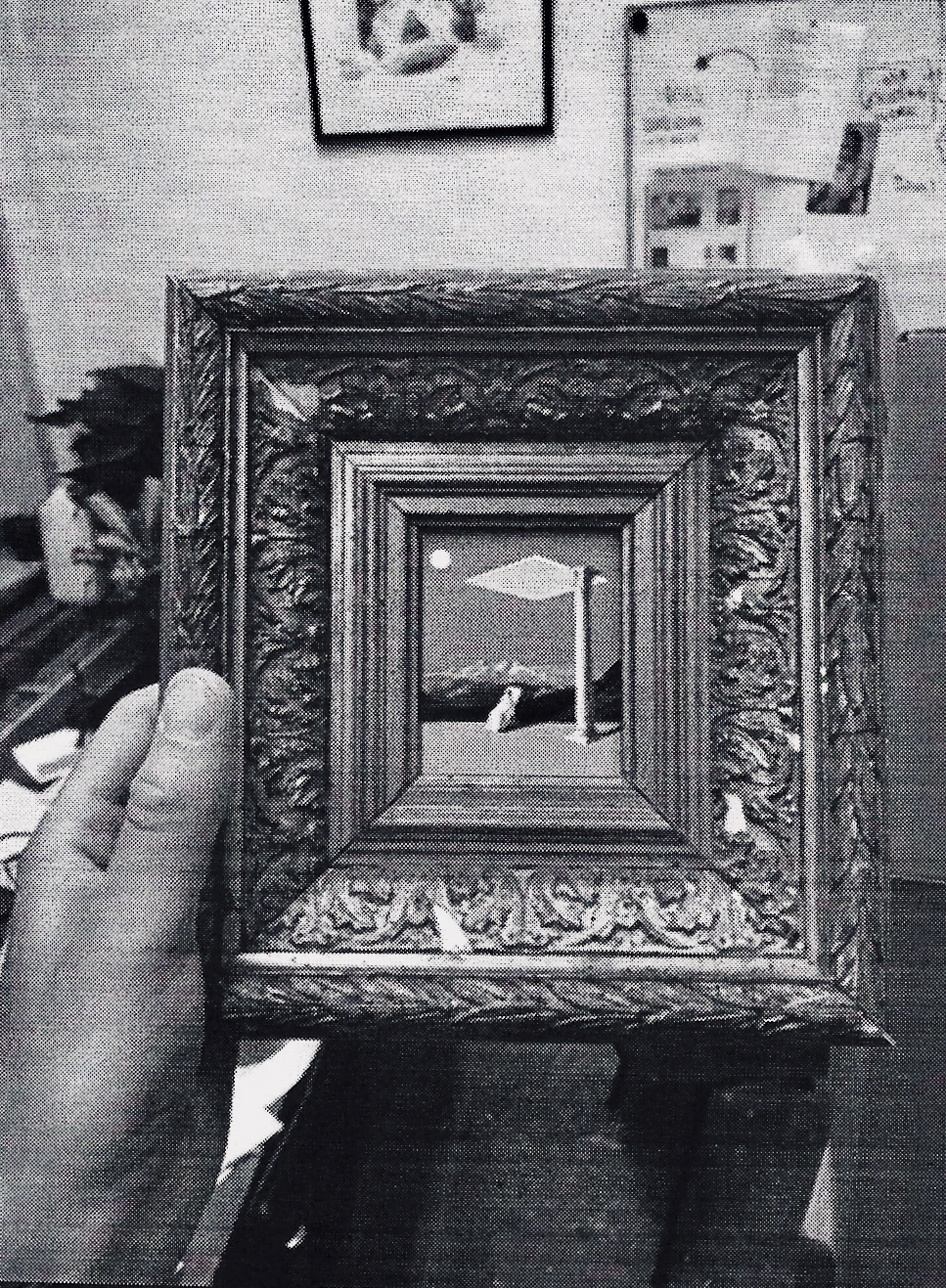

Our Pillar Mister is a partial reconstruction of a vision of the future experienced jointly by Maarten and I while under the influence of a ‘woodland medicine’ gathered, brewed and imbibed at a secret location within an Eastern European old-growth forest, executed in cardboard and other readily available trash-materials.

Pillar Mister is a possible timeline. It is a kind of wish-fulfilment. The elements of Pillar Mister are magic elements. Pillar Mister is an attempt to reorganise the cosmos, to distort spacetime, to open a vertical portal. The pilgrim trails have vanished, along with the pilgrims. The deprived (overworked, underpaid) are channeling their energies into bizarre conspiracy theories about alien lizard overlords and gay frogs. Piller Mister is a reminder. The pillar is empty. Take a seat.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

APPENDIX

The road to redemption had become too easy.

Aviad Kleinberg

![]()

¶ At the height of the Christian ascetic movement—when monks, robbed of the chance to die a martyr’s death by the institutionalisation of Christianity in the fourth century, sought and found creative new ways to demonstrate their love for Christ: ‘… whereupon he met a monk, whose spine was twisted like an olive tree, deformed by the heavy chains he bore; another he spoke with, who was shut inside a wooden barrel; and in a mouldering cave, by the light of a candle, he saw another who, to prove his hatred for the flesh, slept endlessly… and still another he came upon in the hills, who went on all fours like a beast, and ate nought but roots and leaves…’ †—a young zealot named Simeon Stylites gained renown for pioneering an especially hardcore form of self-abasement, living on a small platform at the top of a series of stone pillars, each taller than the last (the final pillar was eighteen meters high). Fully exposed to the elements, teeth falling out, ‘thighs… rotted with the dew’ ‡, Simeon’s fame grew to such an extent that on occasion he received visits from the Roman emperor himself.

![]()

Eventually a double wall was built around the pillar to shield his prayerful contemplations from ‘the distracting clamour of an ever-expanding crowd of weeping fanboys’ §. (Women were not generally permitted inside the compound—not even his own mother. She quietly accepted this refusal, submitting to a life of silent prayer.) After his death a vast edifice was erected in his honour, consisting of four basilicas built out from an octagonal court towards the four points of the compass to form a large cross. The ruins of this structure can still be seen today, about thirty kilometers north of Aleppo.

On 12 May 2016 the base of Simeon’s column, which stands at the centre of the remains of the octagonal court, was reportedly struck by a missile fired from what appeared to be Russian jets backing Assad’s government during Syria’s ongoing civil war.

Our Pillar Mister is a partial reconstruction of a vision of the future experienced jointly by Maarten and I while under the influence of a ‘woodland medicine’ gathered, brewed and imbibed at a secret location within an Eastern European old-growth forest, executed in cardboard and other readily available trash-materials.

Pillar Mister is a possible timeline. It is a kind of wish-fulfilment. The elements of Pillar Mister are magic elements. Pillar Mister is an attempt to reorganise the cosmos, to distort spacetime, to open a vertical portal. The pilgrim trails have vanished, along with the pilgrims. The deprived (overworked, underpaid) are channeling their energies into bizarre conspiracy theories about alien lizard overlords and gay frogs. Piller Mister is a reminder. The pillar is empty. Take a seat.

APPENDIX

The road to redemption had become too easy.

Aviad Kleinberg

¶ At the height of the Christian ascetic movement—when monks, robbed of the chance to die a martyr’s death by the institutionalisation of Christianity in the fourth century, sought and found creative new ways to demonstrate their love for Christ: ‘… whereupon he met a monk, whose spine was twisted like an olive tree, deformed by the heavy chains he bore; another he spoke with, who was shut inside a wooden barrel; and in a mouldering cave, by the light of a candle, he saw another who, to prove his hatred for the flesh, slept endlessly… and still another he came upon in the hills, who went on all fours like a beast, and ate nought but roots and leaves…’ †—a young zealot named Simeon Stylites gained renown for pioneering an especially hardcore form of self-abasement, living on a small platform at the top of a series of stone pillars, each taller than the last (the final pillar was eighteen meters high). Fully exposed to the elements, teeth falling out, ‘thighs… rotted with the dew’ ‡, Simeon’s fame grew to such an extent that on occasion he received visits from the Roman emperor himself.

Eventually a double wall was built around the pillar to shield his prayerful contemplations from ‘the distracting clamour of an ever-expanding crowd of weeping fanboys’ §. (Women were not generally permitted inside the compound—not even his own mother. She quietly accepted this refusal, submitting to a life of silent prayer.) After his death a vast edifice was erected in his honour, consisting of four basilicas built out from an octagonal court towards the four points of the compass to form a large cross. The ruins of this structure can still be seen today, about thirty kilometers north of Aleppo.

On 12 May 2016 the base of Simeon’s column, which stands at the centre of the remains of the octagonal court, was reportedly struck by a missile fired from what appeared to be Russian jets backing Assad’s government during Syria’s ongoing civil war.

† Socrates of Lebedos,

An Ecclesiastical History (New York & London: Arc Press, 1978), p.829.

An Ecclesiastical History (New York & London: Arc Press, 1978), p.829.

‡ Alfred, Lord Tennyson, ‘St Simeon Stylites’

Et cetera ...

Although I be the basest of mankind,

From scalp to sole one slough and crust of sin,

Unfit for earth, unfit for heaven, scarce meet

For troops of devils, mad with blasphemy,

I will not cease to grasp the hope I hold

Of saintdom, and to clamour, mourn and sob,

Battering the gates of heaven with storms of prayer,

Have mercy, Lord, and take away my sin.

Let this avail, just, dreadful, mighty God,

This not be all in vain, that thrice ten years,

Thrice multiplied by superhuman pangs,

In hungers and in thirsts, fevers and cold,

In coughs, aches, stitches, ulcerous throes and cramps,

A sign betwixt the meadow and the cloud,

Patient on this tall pillar I have borne

Rain, wind, frost, heat, hail, damp, and sleet, and snow;

And I had hoped that ere this period closed

Thou wouldst have caught me up into thy rest,

Denying not these weather-beaten limbs

The meed of saints, the white robe and the palm.

O take the meaning, Lord: I do not breathe,

Not whisper, any murmur of complaint.

Pain heaped ten-hundred-fold to this, were still

Less burthen, by ten-hundred-fold, to bear,

Than were those lead-like tons of sin that crushed

My spirit flat before thee.

Et cetera ...

§ John Ransom, Queer Hagiographies

(London: Yello Press, 2009), p.138

(London: Yello Press, 2009), p.138

An email exchange

with Kim Charnley

Author of Sociopolitical Aesthetics (Bloomsbury, 2021)

I.

Hi Sam,

Sorry for the delay. It reads very well (of course)—and provokes the following questions, in case they’re of interest.

There is an ironic ‘light’ tone employed in the depiction of extreme self-mortification in the ascetic tradition. What is the relationship between a kind of hawker’s invitation to ‘take a seat’ and a tribute to Christian ascetics, or ‘vision of the future’? Is the ironic tone intended to provoke? That is, to indicate to the viewer that their casual and uncommitted leisure experience of appreciating contemporary art will very soon encounter forms of actual self-mortification, due to the inevitable constraints that emerge from climate collapse, say? Probably not.

The text also says that the tribute is a kind of ‘wish-fulfilment’, and a mushroom vision, like a combination of avant-garde aesthetics (ivory tower, etc) and extreme sports—or even an attempt to overcome the whimsical reputation of the arts by martial values? As though the artists actually wish that someone believed in something that intensely nowadays… Perhaps it hints at a kind of civilizational declinism, that the problem with the world today is that there are no longer unifying beliefs, of the kind that Christianity once provided?

Finally, it refers to conspiracy theory as one of the manifest problems of the present day—i.e. that the mass of people in supposedly advanced societies seem to actively desire, find agency and solace in, irrational narrative explanations of the end times: in which case, the pillar is the weary and self-ironising place of retreat of the rationalist, tired of having to explain basic scientific principles to the horde.

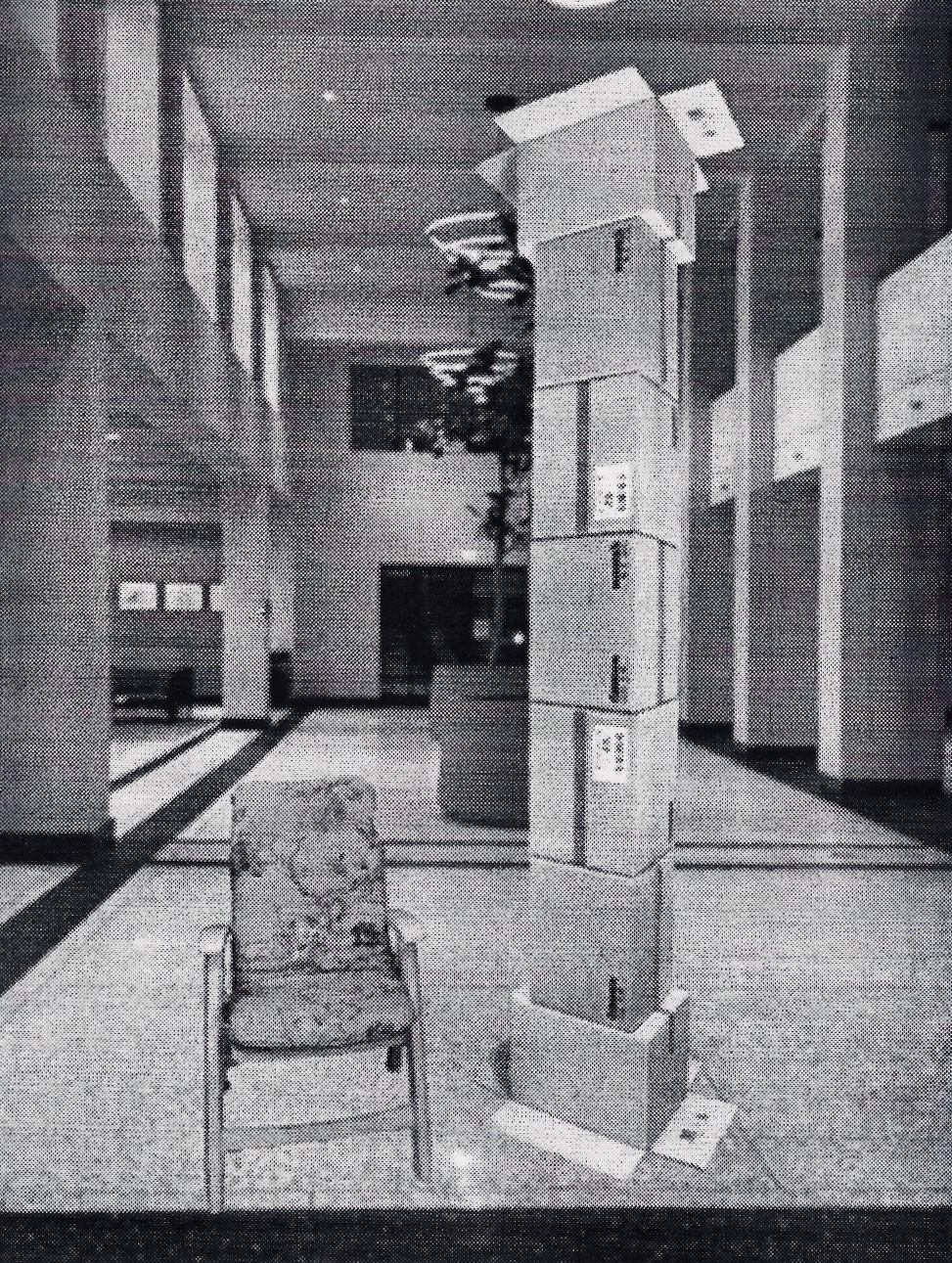

All of these seem like possibilities. I like the proposition of the work—and that it seems to be a pile of boxes, in the previsualisation that you shared. There is obviously a seat at the bottom, rather than at the top, which seems like something for me to think about.

My only cautionary note is that a breezy ironic tone has to be handled carefully. The space of contemporary art is so open that the irony can dissipate and almost seem like an effort to conceal something.

All best wishes,

Kim

II.

This is great, Kim! Can we include your comments in the exhibition?

I suppose the tone arises for several reasons. Probably one of them is a fear of being genuine, because of the very real and careful research that would likely entail.

The tone also gave us permission to do the things we did with the text—like making up quotes and references, and playing a little fast and loose with the facts…

Plus, we really do think that the things these guys did (ruining their bodies, hating life and flesh) were odd and stupid and destructive, and that at its core the Christianity that developed out of Christ’s teaching was fucked up and wrong. What has competitive self-flagellation got to do with creating God’s kingdom on Earth?

So we wanted to make them—the ascetics and their practices, that is—seem silly, with our ironising tone, because we think they were silly.

Perhaps I should add something about how, mad with fame, conceited and maniacal, Simeon began issuing political and theological edicts from atop his pillar; and that, fearing the wrath of the venerated monk (and of his weeping fanboys), the authorities were forced to concede to his wishes? Might ring a few bells…Populism from the pulpit?

Regarding vision, and sincerity, and so on—part of what I had in mind was that book by Philip K Dick [The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch] in which the characters, to escape the horrors of their reality and enter a drug-induced fantasy world, use props.

I felt this idea (‘visionary props’) (1) gave us permission to create something lo-fi—a kind of conceptualism-meets-lowbrow junk culture—and (2) might encourage the viewer to use their imagination. Money constraints played in here too, of course.

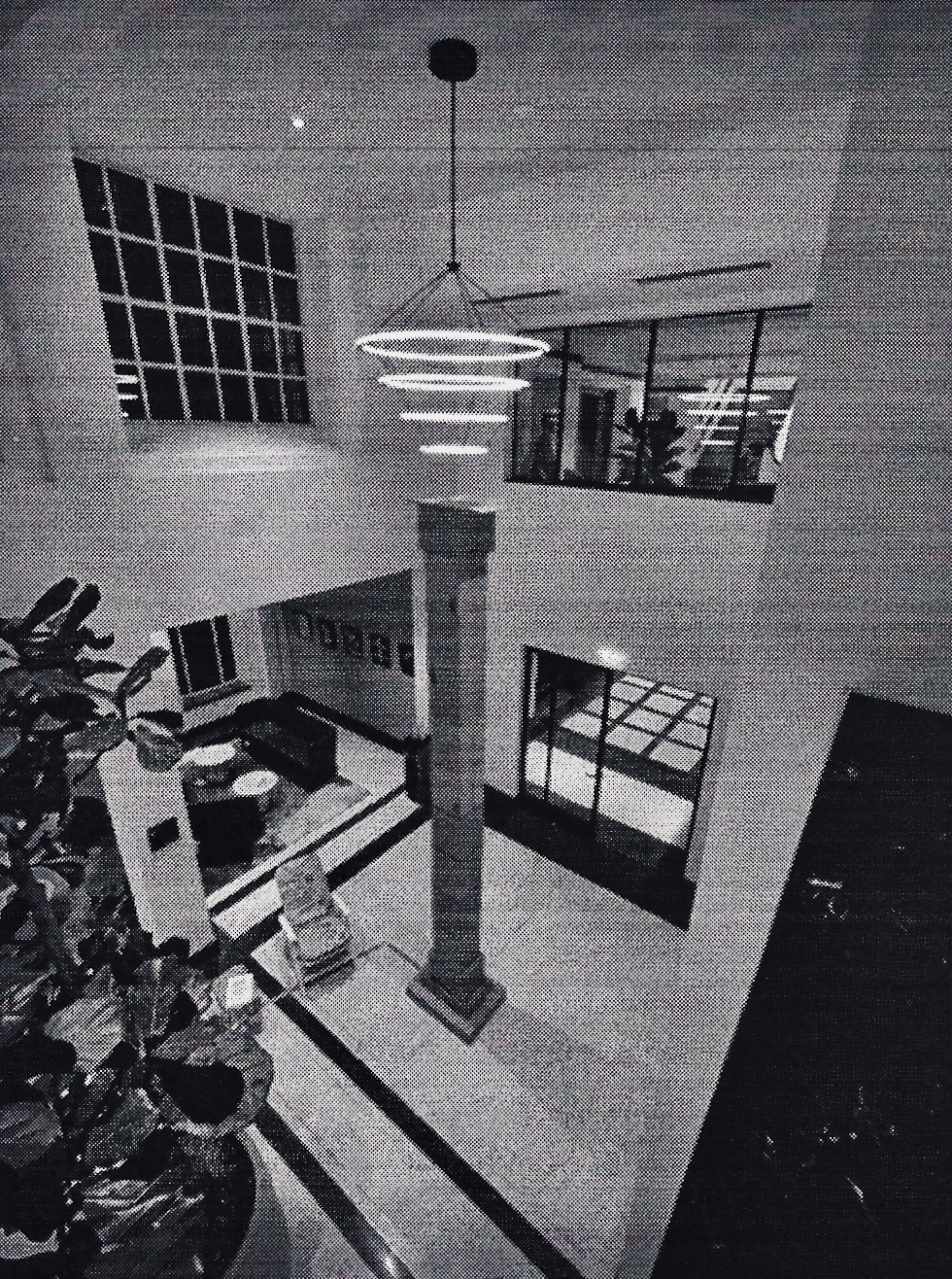

Also, the work is part of a group show which is basically about how the local authorities want art but aren’t really prepared to make space or provide proper funds for it. An example: we were supposed to receive confirmation of the funding months beforehand; in the end, we got it just two weeks ahead of time. Which meant, obviously, that we had to go ahead and create the work without any money…

(Which, we know, is the norm in the rest of the world!)

Apparently the space (which isn’t really a proper art gallery: it’s the expansive foyer and atrium of the city hall) is often cluttered with cardboard boxes. We hope these will add to the ruinous effect. Round the decay / Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Sam

III.

Thanks—this is really helpful. Yes, happy to have responses included if I can have sight of them before they are finalised.

I think it is fascinating the authority that ascetics had. It’s important to note that this authority existed in the context of a more or less ruthless exercise of imperial power by the latter end of the Roman empire, and its successors (Byzantium, etc). Christianity arguably created an unprecedented form of dialogue with Imperial power. Nietzsche wasn’t a fan… But could this kind of authority from below have emerged before the advent of Christianity?

(Were there non-Christian ascetic cults?)

There is an analogy to present day populism, but I kind of want to unpack it and to ask how an ironic address interacts with it. Some of present day populism has a religious basis and it does sometimes have a masochistic dimension (in that it is opposed to ‘snowflakes’, and defends all kinds of regressive and barbaric practices). On the other hand, populism operates now in the context of a consumer society that celebrates sensuality, in so far as it is a good way of selling people things.

I think a critique of Christianity is definitely warranted, but personally I think it ought to be balanced against those elements of Christian ideology that resist exploitation, or it might default into a standard bit of rationalist religion-bashing.

But that’s beside the point, perhaps. The key thing is, how much does the use of irony need to be balanced against the inclusion of elements that signal the political intent of the work? If that makes sense. I don’t mean that it should made ‘didactic’, just that ambiguity needs to be quite carefully calibrated sometimes…

Anyway, I should conclude by saying that I love the material!

Kim

IV.

Yes! I agree, totally. That’s why I was keen to say, ‘the Christianity that developed out of Christ’s teaching’, to distinguish the content of Christ’s message from the subsequent institutionalisation of Christianity.

Though as you say, Christianity was instrumental in both calming things down and opening things up.

But I am also keen to say that the work isn’t really an argument of any sort! It does not cohere in that way. The work is not a critique of Christianity! Nor is it a critique of populism!

Part of what I want from art is a kind of reckless energy: an energy it gets from clashing and unresolved parts, as well as forward drive.

Sam

V.

Absolutely—I get what you are saying about the work not being an ‘argument’ as such. Completely agree. I also find that what is interesting about contemporary art is its capacity to hold together ‘clashing and unresolved parts.’

Adorno said of works of art that ‘the elements are not arranged in juxtaposition but rather grind away at each other or draw each other in’ (Aesthetic Theory p.251-252). I think it is this capacity to hold an unresolved contradiction in place that I find compelling.

Arguably, works of art do nonetheless have conceptual content, which they can hold in something like a constellation, or network, without subordinating it to strictly logical development, or presentation in the form of an argument. But the key question is, does an ironic tone actually keep open a force-field of this kind, or does it actually close it down and make it more resolved? I think the answer is ‘it depends’—there are a lot of thing to weigh up.

But that’s why I thought it was worth reflecting on the role(s) that irony can play in mediating the commitments of a work like this. In the last analysis, works of art are always founded in commitments, or they ought to be. Interesting to discuss these things!

Kim

ENDS

Sam Wilson Fletcher is a British-Irish artist. He was born in Lewisham, London and studied chemistry and quantum mechanics at Oxford and geosciences at Harvard and the German Research Centre for Geosciences. In 2022 he was artist-in-residence on expeditions to Antarctica and the Canadian Arctic and Greenland, as well as aboard a ship crossing the Atlantic from Amsterdam to Quebec City. Recent publications include CURSE TABLET (Slub Press, 2023) and New Adjacent Possible Empty Niche (Veer2, 2022).

Maarten Slof is an artist and a key member of Dutch art collective ROEM. He studied Design and Architecture at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague.

Kim Charnley is Staff Tutor in Art History at The Open University, UK.