Rehearsal / 21. Jeffrey Vallance / ‘Our Private Eye’

(A conversation with Jon Auman)

![]()

(A conversation with Jon Auman)

Jeffrey Vallance is our Philip Marlowe, quite literally our private eye,

with a private vision of pied beauty and sacred banality that extends

to the horizon.

Dave Hickey

The artist Jeffrey Vallance and I spent the worst of the pandemic years working on the project that became Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings. Throughout that time, we rarely went a day without emailing each other. But, for reasons neither of us quite understand, we never spoke on the phone or tried to schedule a video chat. The following interview is thus a record of the first time that we spoke to each other using our own voices. A big thank you to Jeff for suffering through all of my questions and offering us a window onto aspects of his art-making and writing that have received less attention than they deserve.

Auman, MMXXIV

![]()

![]()

ORDER A COPY OF VALLANCE’S VOYAGE HERE

Jon Auman So, you wanted to ask the first question?

Jeffrey Vallance I remember when you first contacted me, you said you’d been in a used bookstore and found my book [The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978–1994] misplaced or misfiled on the shelves.

You opened it up, and you liked it. Can you explain more about that?

![]()

![]()

It was a used bookstore in downtown Manhattan. I don’t know why, but in used bookstores I always forget about the Travel section. Then, of course, whenever you go and look at it, you think: ‘Why do I never look at this?’ I think I was waiting for someone, and I’d already looked through all of the other sections. So, I thought I’d look at Travel. I saw this thin spine that said ‘Art Issues Press.’ That rang a bell. It seemed like a weird publisher to have in the Travel section. Then I noticed the title: The World of Jeffrey Vallance. Usually when you see something called The World of so-and-so, it's The World of Jacques Cousteau. I thought, what is this thing? Then I picked it up and looked inside the front cover. The bookstore was pretty dark, and I thought the first page looked water damaged. Then I realized it wasn't water damaged. The book is beautifully printed, and the first page has this very faint image of the Shroud of Turin printed on brownish-yellow paper. Again, I thought: “What is going on here?” I kept flipping through it, and there's stuff about a frozen chicken named Blinky…

Yeah, and it does say ‘Art’ right on the spine. But…

I was very interested in how this book wound up in the Travel section. Maybe someone at the bookstore opened it to one of the essays about Tonga and thought: ‘Right, Travel.’ But, I also don’t think it's out of place in the Travel section.

They could have put it in every other section too.

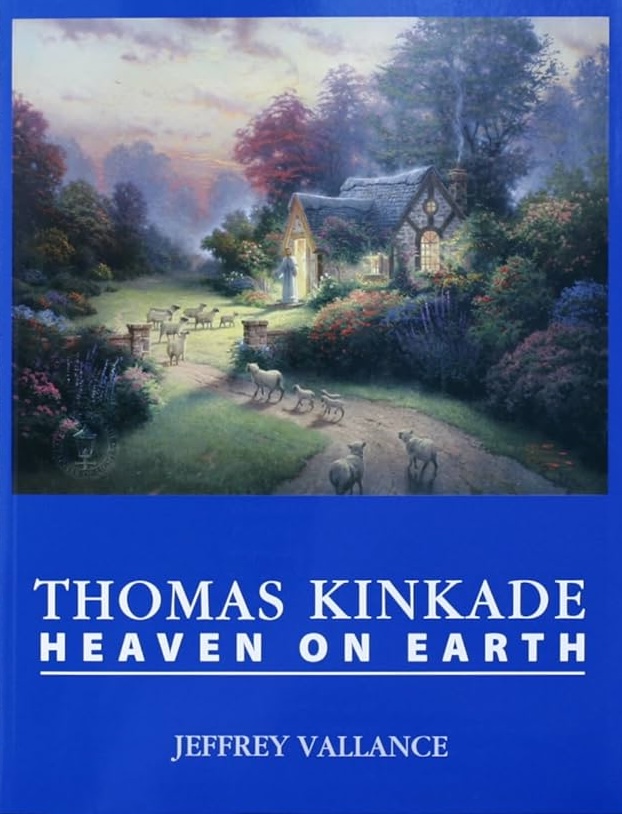

That was part of what excited me. It’s funny, because a few months later, I went to the same bookstore, and they had the catalogue for the Thomas Kinkade show that you curated, Heaven on Earth, on a table at the front.1

People usually think that my stuff is fiction for some reason. It’s interesting. The fiction thing comes up again and again.

I can see where someone could get confused and think these stories are fictional. I wonder if it has to do with the way you present your subjects. You’re very matter of fact.

Right.

Often, when someone’s writing about a Bigfoot myth, for instance, it’s done in a tone that's very National Enquirer. It’s over the top and trying to be salacious. Whereas, you’re always writing in this specific tone that’s very ... you’re not being sensational. If it’s funny, if there’s humour there, you’re not laughing down at anything.

I think I naturally talk in a kind of deadpan voice. So, maybe that comes through in the writing.

It takes a minute for people to adjust to that tone. When someone first comes to one of your essays, they're thinking, ‘Okay, this is about Martin Luther and his love of working on the toilet.’ Luther is worrying that he’s going to be attacked by the devil while he’s on the toilet. It’s very funny. When you get into the actual research, it doesn’t become less funny. But the reader very quickly realises that it’s not just a gag. You’re talking about actual history.

That’s exactly it. That’s why I like writing about those things. Because it seems so absurd. It’s so incredible. But that’s how it really was. As opposed to what they taught us when I was going to Lutheran school as a kid. They wouldn’t mention anything about that, which would actually have made Luther very exciting for a student, you know? The real story!

It’s similar to when you write about meeting the King of Tonga. You’re always being very respectful to the person. You’re just saying how they were / are. That’s it.

And I ended up liking them better afterwards. After doing the research and doing the writing, I feel like I’ve really made a connection.

![]()

How did you start writing these kinds of pieces?

Were you already making art, and then writing is something that came later?

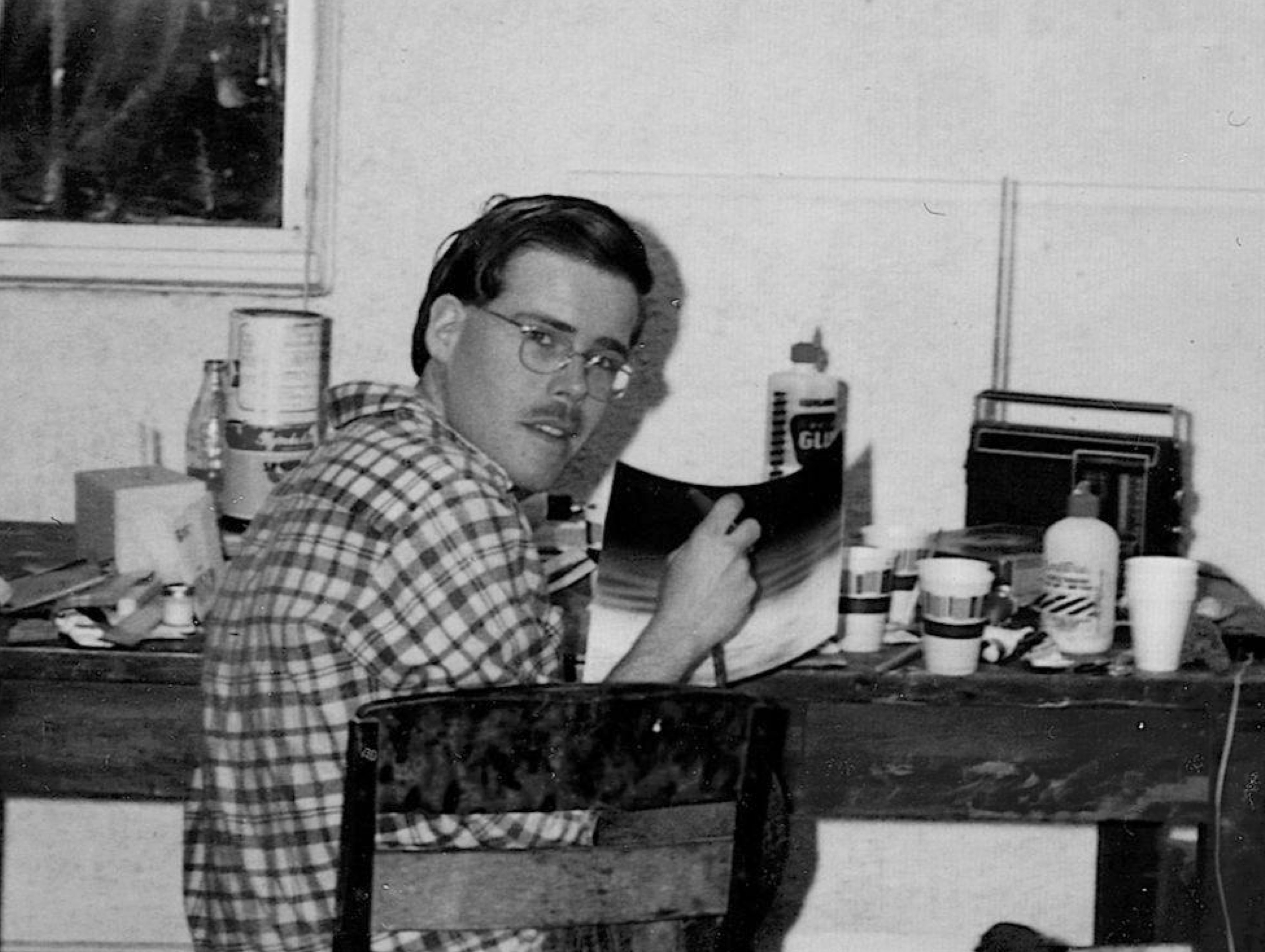

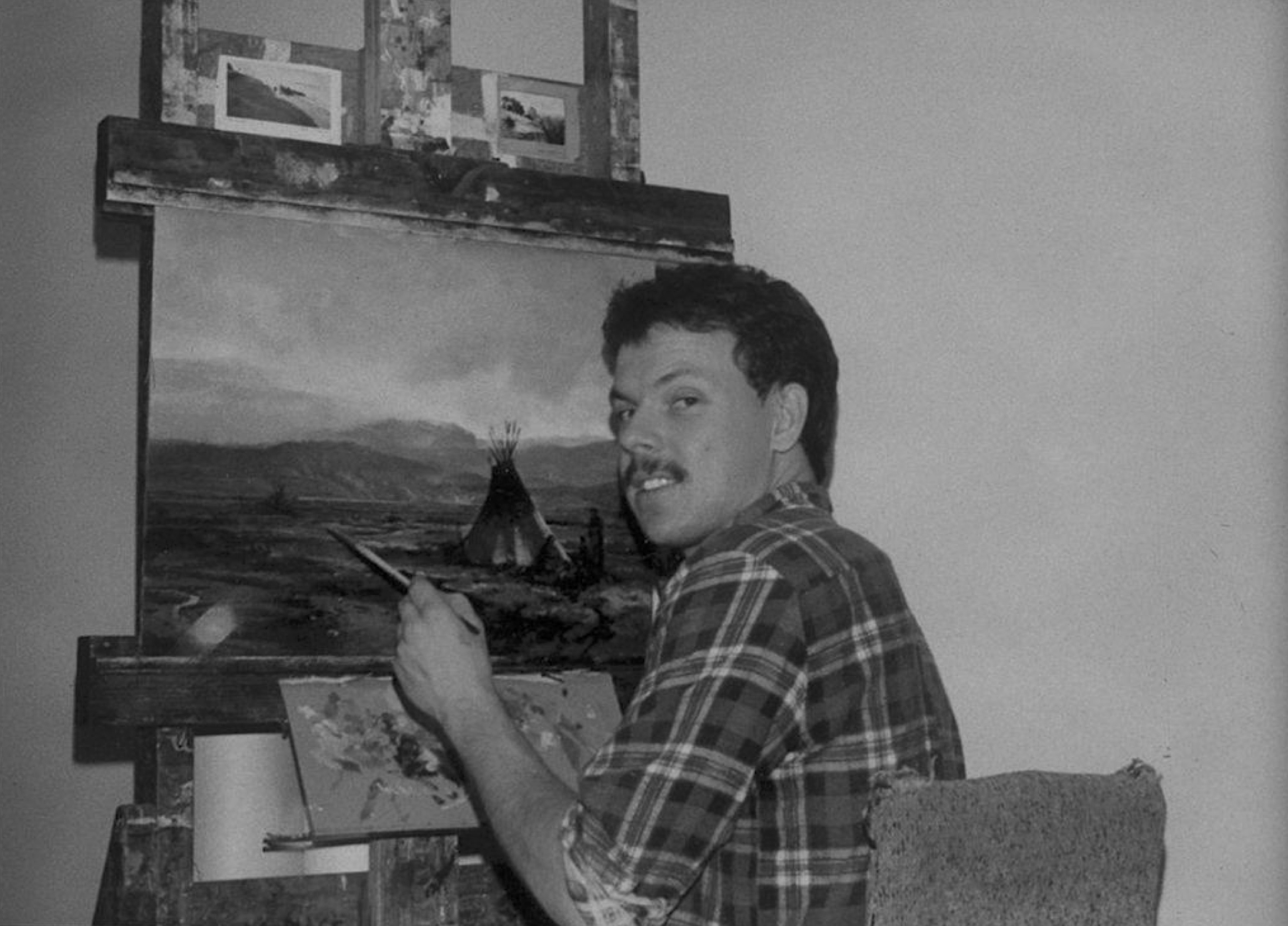

It’s a two step process. Before art, before anything, I liked telling stories, and I liked telling them in a certain way. It’s deadpan, and there is some humour. That was developing, this way of thinking. Then I started doing art. I started doing exhibitions. Much of that early work was very conceptual. At first, the writing was for wall labels. I would write these expanded, paragraph long wall labels that told you what this thing was that you were looking at. It would give some background. Over time the wall labels started to expand. Suddenly it wasn’t just a paragraph, it was a page, and then it was a whole story. I’d have handouts at the galleries. You could pick those up. Then people would ask me if they could publish them. They did end up in travel magazines and art magazines and punk magazines, in all of these different places.

There’s a long history of artists writing, particularly about art. But I struggle to think of other artists who’ve written so much on other subjects. You write a lot about art as well. But you also write about history. You write travel pieces. When you started writing these essays, were you already thinking of it as a project? In retrospect it all seems very cohesive.

When I put The World of Jeffrey Vallance together—the one that you found—I hadn’t considered the writing as a whole body of work. But when it was published, I realised that almost every piece is connected to the piece that came right before it. I saw it as creating this whole. By the 1990s, when I was writing the stuff that's in the second book, Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings, I sort of knew that was happening, that each piece connected to the one before. I just thought, well, maybe one day, if somebody publishes it, there will be these little clues. It was done on purpose. But it would have happened anyway, because I follow where the research goes.

Another aspect that we always talked about when we were working on the book was the importance of specific places. Eventually, it became the organising structure of the book. How does traveling work for you? Do you start with an idea of a place that you want to go?

It’s an entire process in my art. I come up with an idea for a new piece. The genesis is always an earlier piece. Maybe there was one detail from the last piece that becomes the entire new piece. The first thing I do is a lot of research. I try to get every book on the subject, and I read this stuff for years to find out every detail. Then, when I’m ready, when I see the focus of the piece, there’s no more reading that I can do, and I have to go there. Because I know that will be a totally different experience. There’s so much that’s not in books. Even if you read every book, there’s still more. Part of the process is that I always want to meet someone connected to the research. Whether that’s a director of a museum or a priest or the King of Tonga or a psychic. I want to bring in these ultimate experts in whatever field. Usually, I bring them a gift or something, and that induces a certain kind of conversation. So there’s the traveling, and then I come back. I start writing the text and making objects, whatever those are. It might be drawings, or it might be a painting or sculptures or collages or video or a more conceptual piece. I make things based on which medium will tell the story the best.

I think part of what connects the essays is the amount of research you do. You can feel that you know what you’re talking about. But also the voice or the tone that you write in makes it feel like we're seeing different things through the mind of the same person. I’m curious, do you think of that “I” or “Me” as yourself? Do you have a character that you write in? Is it conceptual in that way? Or, do you even think about it?

I don’t really think about it. Because I think of it as myself in that situation. When I’m talking to the King of Tonga, it's just myself talking to him. Afterwards, I try to remember everything we said and try to make some kind of sense out of it. I try to not forget any details. After meetings I go back and immediately make pages of notes. Otherwise something will disappear, some piece of information. People have said that the tone of the writing almost sounds like an encyclopedia, that it's like the voice of knowledge, but with deadpan comedy mixed in.

I was flipping through The World of Jeffrey Vallance, and there's a piece called ‘Blinky, the Friendly Hen.’ In it, there’s a little sidebar titled ‘Chicken Sex Change.’ It says...

All you’re doing is stating facts. But when you state the actual facts of the situation, they sound completely absurd.

Blinky is a good example of that. That was a long time ago, in 1978. Back then I didn't think about things the way I do now. With the Blinky piece, everything was spur of the moment. Oh, here's an idea, I'll bury a chicken! Okay, I'm gonna go do it. And now I'm doing it. Then there it is. It's buried, and it’s over. So, I never thought about the meaning of it, or why I did it, or why did I choose certain symbols or certain ways of doing things? I wasn’t thinking about any of that at all. When I wrote the piece that you just read from—which is from at least 10 years later—I realised that the whole Blinky saga was kind of like I was acting out a pre-existing myth. All the steps that I took, that I thought were purely random, were related to different rituals and myths from around the world involving the chicken. It really made sense in hindsight. It was shocking to me that I was acting out all of these different rituals from different lands and different times, without knowing that I was doing it. It was really powerful and spontaneous, and I could see that it was connected to this whole body of work.

There’s a piece in Voyage to Extremes that’s basically you going through all of these different instances where the chicken is used as a symbol by different faiths and different cultures from all around the world. When you read that piece and then you go back and look at Blinky, there is something really profound there. This frozen chicken seems to have a limitless potential for meaning. You could ponder it forever. It happens again and again in your work. You start with something like a frozen chicken in a supermarket in a suburb somewhere, and it doesn’t take long to get from that point A to a point B that’s dealing with the sacred and / or the profane. Dave Hickey talks a lot about Raymond Chandler in his introduction to The World of Jeffrey Vallance. He says your essays are like mysteries, and that you’re the detective jumping from one clue to the next. I think he’s right. At a certain point, like in a lot of good crime novels, the desire to find out who the murderer is falls away, and what’s left is the pure pleasure of description and making connections. Is it strange to go back and think about these older pieces again? Some people hate looking back at anything.

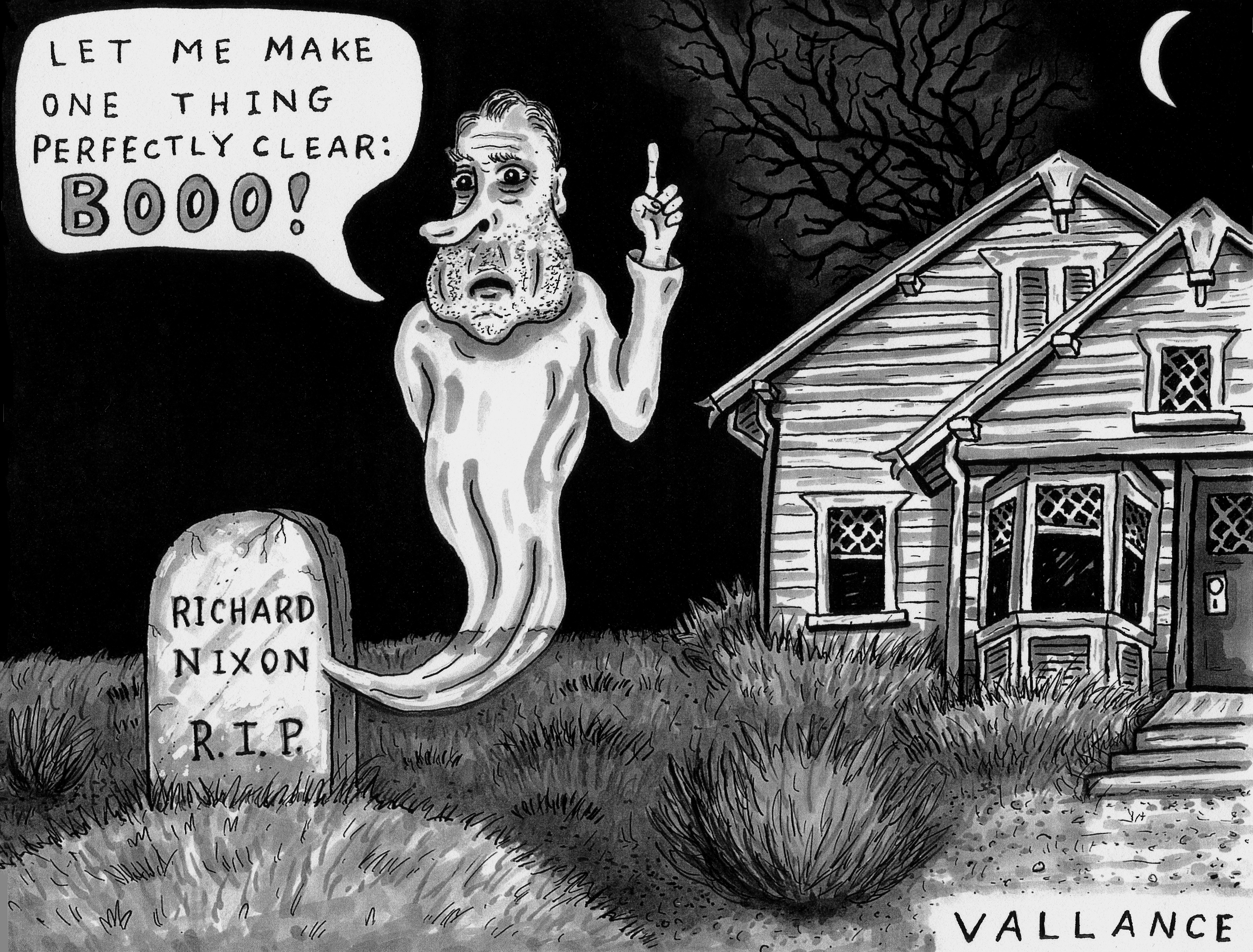

That’s another huge question. I can only answer the tip of it. When you mentioned the word strange... The example that I think of is the ghost story about Nixon. The first version of it was very short, like a paragraph.2 I actually went to the Nixon library. The essay was about how I would feel if there was a ghost, and what the ghost would do. It wasn’t saying that this was true, but it seemed likely, so I wrote the story. Then, somehow, it got on the Internet. These two guys, Joel Martin and William J. Birnes, wrote a book called The Haunting of the Presidents about the ghost stories for every president. Of course, they had Nixon. Their Nixon story was based on my paragraph. It was really obvious because they basically took every sentence from my story and expanded each one into several paragraphs until they had two chapters. But, that wasn’t the weird part. At the end of every ghost story, there was a section where the authors hired a psychic that would channel the president and then ask him if the ghost story was true. They did that with Nixon, and the ghost of Nixon said the ghost story was completely true. When I was reading this, my eyes were bugging out. When you have the actual ghost say the story is true... But that wasn’t even the strangest part! So the ghost of Nixon is talking, and then all of a sudden the ghost goes on this tangent. It starts talking about the writer of the original ghost story, and you could very clearly tell that it was talking about me. It couldn’t be anyone else. It was talking about how the writer collects Nixon stuff and was part of the campaign—all sorts of stuff, and all these facts. My eyes were really bugging out, but it was great. It's like Nixon's ghost pulled a prank on me. It was as if the ghost said, ‘If you're going to pull a prank on me, then I'm going to prank you back.’ I love when the stories go in that direction.

![]()

When did you become interested in the paranormal? It comes up again and again in your work.

When I was a kid I was really fascinated by The Addams Family TV show. I didn’t really know what it was about or why I was attracted to it. But I realised later that I wanted to be in that family. They were all weird people doing weird and outrageous stuff. But it felt normal to me, like I'd found a normal family that I could be a part of. The Addams Family opened up a lot of stuff. Monsters in general. Hot rods and monsters like Rat Fink. It started this whole lifetime of interest in weirdos and monsters. Then, around 1977, I read the works of Charles Fort. He was this guy that collected newspaper clippings about all of this totally weird shit. Every kind of paranormal thing. He was kind of like the father of all things paranormal. He was the first person to talk about different concepts that we now take for granted. He was also very funny and very deadpan. And he lists a lot of facts. So, it's really those two authors: Charles Addams for monsters and Charles Fort for the paranormal.

I’m curious how people in the art world responded to you putting these kinds of things in your work. It’s making me think of that time—how many years ago was it?—when they found that big metal obelisk in the desert and no one knew what it was or who had made it. Someone started a rumor that it was a John McCracken sculpture that he'd made to communicate with UFOs. Something like that. I feel like people in the art world are very uncomfortable with talking about things like UFOs. They like John McCracken, the nice minimalist sculptor, and want to leave it at that. I thought it was fascinating, and McCracken was very interested in UFOs.

I love stuff like that. That’s what I live my life for. When these two unrelated things suddenly come together and create a new body of knowledge. I always thought it was odd that I'd write these things that are totally paranormal, then they’d publish them as articles in art magazines. I wasn’t writing art criticism or anything, but somehow it fit in an art magazine. I don’t know how that's possible. Then, when the art museums and art magazines stopped wanting to do that, I started writing for Fortean Times, which is a paranormal magazine. But I often find myself writing about art there, in a paranormal magazine.

I was thinking about the research that you do for these pieces. Are you the kind of person who, once you’ve researched something, you file it in the back of your mind and revisit it? Or—when you're done with a subject—are you done with it forever?

I’m never done. Ideas can always spring up again suddenly and connect to something else. Out of nowhere they can take on this new life. I think that’s why the stories connect. It’s like with the Blinky story. There’s two major stories. There’s the original piece, and then the second one came from reading the Bible. There’s one passage that really got me. It’s Jesus talking about himself. He compares himself to a mother hen with her chicks. Immediately, I thought about all of these other images of Jesus, like the dove and the lamb of God. No one wanted to take on Jesus as a chicken. But, he compared himself to one! So, I thought: ‘Isn't this an important idea?’ So that’s where one of the later texts comes from. When I did more research, I realised that it’s in every religion—shamanism, Buddhism, Islam. The symbol of the chicken is central, yet no one ever talks about it. I did more research and found out that the area Christ was living in was, at that time, the poultry capital of the Earth. Of course, he knew about chickens! They were everywhere. It totally makes sense. He didn't choose the image of the chicken at random. It was something he saw every day.

You see that throughout the Bible: snakes, dusty mountains, the red sea with some boats on it. There are big, miraculous events that happen, but a lot of the Bible is obsessed with quotidian, everyday life. There are a lot of rules and regulations for the most mundane things. To change the subject slightly. Are there writers who were important to you when you were starting to write?

Herman Melville. Especially Moby Dick and its obsession about one thing, about whales. Melville goes on all of these tangents about Whales, then he comes back to the story. That was really important. This singular idea that you can expand on. A lot of what I read aren't novels. I read a lot of scientific manuals on different subjects, like on chickens or anthropology. I love to get books related to what I'm thinking about. With Melville, I loved all the details. Another one is Joseph Campbell. Maybe I like all of these things that take an idea and expand on it, and then connect it to other things along the way.

It allows you to talk about a lot of different subjects from an angle that doesn’t feel too aggressive. I don’t think of your essays as aggressively ideological. You write about heads of state that you meet. There’s the Marion Barry piece. But I feel like you’re letting these people speak for themselves.

I like to do that because you could start off saying you either hate this person or you like this person, and then make that the basis of what you're writing about. But, I would rather let people find that out for themselves in the writing. One example of that is the story I wrote about Ronald Reagan's ghost. It's been written about extensively by right-wing writers, like Bill O’Reilly in Killing Reagan. At some point they adopted the ghost of Ronald Reagan and made it their champion. They made it a part of their philosophy. There was even a TV movie, called Talker,made about it.3 For me, all of it becomes a part of the story. I just hope that people can pick up on how absurd that is, that they've taken this story completely literally. At some point, they started to be criticised in the Washington Post for talking and writing about the ghost too much.4 That’s perfect. There's this whole domino effect.

A lot of your pieces have these very interesting afterlives. You’re writing about myths, about stories that are being passed down through time, about how they change and become distorted or renewed or inverted. With the Reagan ghost story you can see that taking place in real time. You can see how this small thing that you wrote is taken up by other people who create this new, absurd context for it. You see the actual process of how myths are made. And then these crazy loops start to happen.

Right, loops happen. Then it totally gets out of control. Like with the Nixon story, where it loops back to me and I’m pulled back into it in some bizarre way.

The figure of Nixon comes up again and again. What is it about Nixon—and also Reagan—that fascinates you?

Well, I think part of it is that I was of a certain age. With Nixon, I was a preteen so it made a special impression. All my life I’ve been obsessed with politics. In the past, I guess I had seen politics in a neutral way. I would go to rallies, but I would go to rallies for both sides. I would collect things like buttons and political banners from both sides. It was like documenting history at a certain point. Of course, because of Vietnam and then Watergate, Nixon was the president that I most loathed. I think Reagan was next in that line. I had this philosophy about both Nixon and Reagan, that when they died they were over, like they were immovable and fossilised. Then I thought that writing about their ghosts would continue that history or keep it moving, even though they were gone. You could add more information about them. Which I did for myself. I didn't realise that other people would also pick up on that and start doing it. I saw it as writing another chapter in their histories. You can read these whole biographies about Nixon from birth to death, but then the book stops. But, I thought, ‘No, you can continue on!’ I could write about what their ghost does and how people interact with the ghost.

You’re documenting how a strange fragment that someone said or wrote—or a real, physical fragment, like the Shroud of Turin—lingers through history. With the Shroud of Turin, this is a thing that was draped over someone's body at some point. It was just a cloth. But somehow this cloth has made its way through history. These objects are also kind of like ghosts.

It's all a bit like a ghost. They continue to play a part in people’s lives. I did want to speak about the Shroud... I spent some time in Turin in 1992. I was doing research on the Shroud, and while I was looking at it I found that there were these images of clowns on it. Of course, they were actually the scorch marks from when someone tried to burn the shroud. I wrote about it and presented it like evidence. I mean, in a way, it seems like the most mocking thing you could do. To say ‘Oh, I found clowns on the Shroud.’ But, when you actually look at the research, it totally makes sense. In terms of: if this is a true relic, then who would want to burn it? Obviously, that would be Satan. But Satan didn’t completely burn it. He failed. But he did manage to burn these clown-like self-portraits of himself onto it. I did more research, and in the Middle Ages, clowns were more like a trickster demon, which takes you back to the devil. That project got me in trouble with this group that puts out a yearly report.5 It’s a pamphlet where they list everything that they think is anti-Catholic. They found my column on the Shroud of Turin and thought it was anti-Catholic. So I wrote to those people and told them my whole theory. Then they said, ‘Oh, we understand. We see your point. We'll take you off the list.’ That was when the whole piece became perfect. It’s totally outrageous. There’s clowns on the Shroud! At first it can seem mocking. But if you blame it on Satan, then it totally makes sense again. Now that research reverberates through the groups of people that do research on the shroud. They can’t avoid it. All of these things that I research somehow seep back into the pool of research, which I love. The piece becomes part of the thing itself.

![]()

This is making me think of another piece in Voyage to Extremes. It’s the one where you’re writing short descriptions of different sites around Las Vegas. One of the things you describe is a Weeping Virgin Mary statue in someone’s backyard. It’s the kind of thing that anyone who’s grown up in the US is familiar with. Especially pre-internet, you’d always see stories on local TV news. Someone buys a block of cheese and finds the image of George Washington’s face on it. Or, they see the Virgin Mary burned onto their toast at breakfast. Sometimes when you’d see the image of the block of cheese you’d think, ‘Wow, that really does look like George Washington!’ But you’d snicker at it. In your piece, you describe details like that the statue is in this guy’s backyard. You give the opening hours for when you can visit it. It’s very funny. But then, when you put that piece in the context of your other pieces about the Shroud of Turin... The Shroud is taken seriously by millions of people around the world. But you write about the Shroud and the Weeping Virgin in the guy’s backyard in the same way. You don’t treat one as more sacred or more ridiculous than the other. Doing that makes us think about both of them differently. We start to think about the Weeping Virgin as a cultural relic that people agreed to imbue with meaning. And it also makes us realise that, at some point, the Shroud must have been a funny thing in someone’s backyard. I’m curious how you get this effect. Is it all about the research? You don’t seem to be bringing many preconceptions to these subjects.

It’s about the research. Let me tell you a story about seeing the Weeping Virgin. Somebody told me about it. I think it was in the local newspaper in Vegas. I went to see it. I called to make sure the owners were going to be there since it was in their backyard. When I went out there, it was something like 110°. It was really hot, and the shrine was open to the air. I just expected to look at it. I thought I was going to see this Weeping Virgin, but obviously it wasn't going to be weeping. But, while I was standing there it started weeping. The people that owned it rushed up with cotton balls, soaked up the tears and gave those stained cotton balls to me. So, I had those relics of the Weeping Virgin. I had the weirdest feeling while I was standing there. I figured it was one of two things: either it really was a miracle, or I was being completely tricked. I saw both of those possibilities as equally interesting. It was fantastic. Either way it was fantastic. If they were trying to trick me into believing it was weeping—that's still weird, almost just as weird as a miracle. I had a profound reaction to that. It was a real reaction. I was there. I saw it. Something was happening there. Possibly it was a fraud, but wouldn’t that be interesting too? I’m not saying it was a fraud, but it could’ve been.

Even if you think something like the Shroud or the Weeping Virgin or Bigfoot sightings are completely absurd, the fact that human beings have invested so much time and energy in these ideas is just as fascinating. I do think there’s something about the way that you approach these subjects that makes them accessible to anyone. It’s fascinating that these pieces have circulated in the art world. Obviously so much of art history consists of religious art, but having serious discussions about religious and paranormal topics is pretty rare in that world. The way you write about these subjects seems to allow people to approach them from a different angle. There is something magical about it. A little bit like what you were saying about when you were standing in front of the Weeping Virgin: it allows people to have a real reaction. You disarm their preconceptions.

Well, I agree with you that it's a magical thing. And I’ll take that one step further. I think that all life is a miracle, even the most mundane things. I mean you wake up and everything is the same, and then all of a sudden it's not. The mundane-ness of something makes it into a miracle. If you look at it a certain way, the simple fact that we're alive on this planet is insane. You just have to take a moment and really look at it and you realize everything is a miracle.

That’s exactly what I get from the book. You’re fascinated by everything. It’s a voracious appetite for the things that people do, how the world works, and how it doesn’t work sometimes.

And I don’t want to judge it. I don’t want to tell you what you should believe. I want you to make up your own mind by reading the story. I’m sure people can read these things and come away with different ideas and interpretations.

Part of why I think it was important to collect these individual essays together is that they create even more, and sometimes different resonances when you read them side-by-side. The book has an arc to it. We end up at this sequence of essays about Thomas Kinkade.

Kinkade is a perfect example. In a way he’s a living embodiment of this country’s divisions. He was divided within himself. There were some people who saw him as being like a saint, almost like a Christ figure. They would look at his paintings and receive miracle healings from them. I don’t make fun of that because I believe people really believe it and did get some healing from it. But at the same time, Kinkade always knew that he had a dark side that nobody else knew about. He knew that he was sort of a fuck up. So what do you do with that? People are ascribing miracles to your paintings, but you feel far from perfect. I think it did a number on his head.

![]()

![]()

In one of the last essays, you talk about his secret alter ego, a demonic, leather-clad biker named Ed Aknik ["Kinkade" spelled backwards], that he’d invented for himself. It reminds me of what you were saying earlier about Martin Luther. Finding out about the other sides of these people can actually make us feel closer to them.

It makes him into a real person. Because the other person we’d seen had become a corporate mascot with the name Thomas Kinkade. That Thomas Kinkade wasn’t real. In retrospect, though, it all makes sense. Here’s this young guy who's painting these paintings that look like they're from the turn of the last century. He’s painting these cottages. They’re not hip at all. He’s selling them to senior citizens, housewives, people in the Midwest. It became an empire. You couldn’t do all this stuff and not have some other mode of expression. But again, when I did that show, I had no evidence.

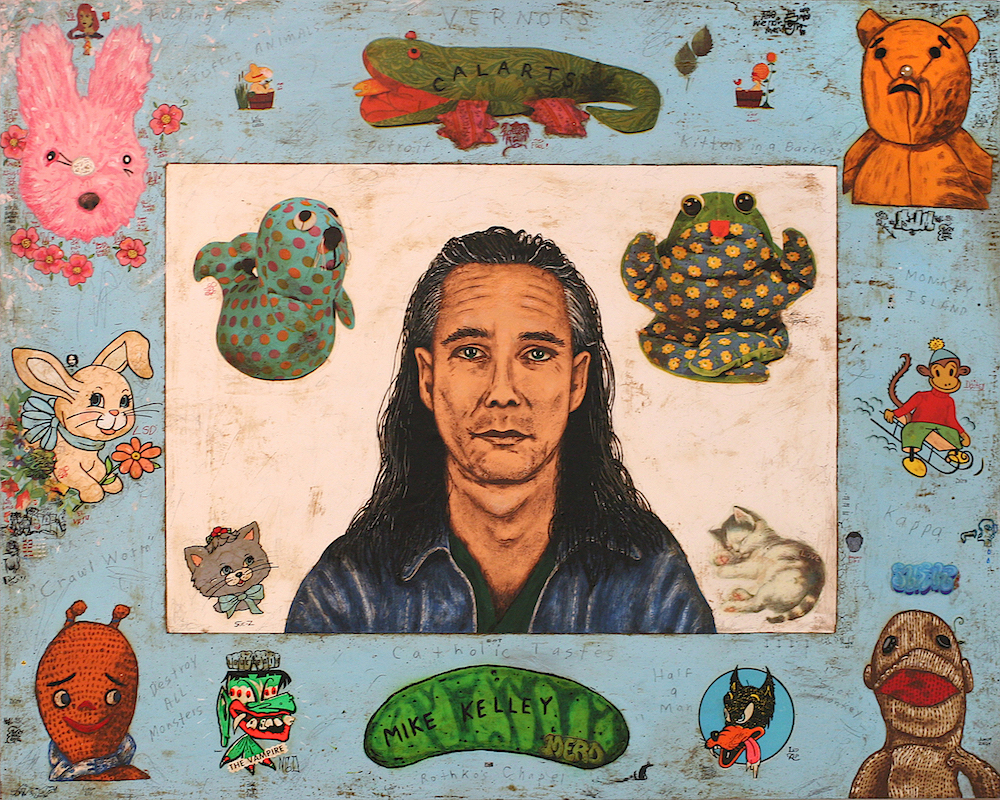

This theme emerges at the end of the book—maybe ‘theme’ is the wrong word—about things that are buried underneath. Actually, this is a good topic to finish on. Recently, someone showed me pictures and videos taken by someone that’s currently working with a team of people who are restoring the Mike Kelley piece that is mentioned in the last essay in the book. The piece is this ranch-style house in Detroit that’s modelled on Kelley’s memories of his childhood home. Underneath the house there are these seemingly infinite layers of underground rooms, hallways and ladders that aren't accessible to the public.

Like psychological layers. Like layers of the mind.

Voyage to Extremes ends with a description of that piece. It’s an incredibly affecting ending for me. I don’t know why exactly. The book is so filled with humor. It’s so pleasurable to read. But, there’s something about the ending that makes me look back across the rest of the book in a different way. There’s a lot of laughter, but also something serious going on.

I think it’s that I take everything seriously, and I find humor in everything at the same time.

![]()

NOTES

1.

See Jeffrey Vallance, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth,

published by Last Gasp (April 2004).

2.

See Jeffrey Vallance, ‘I am not a Corpse (Nixon’s Ghost),’

L.A. Weekly, Sept 30 / Oct 6. (1994).

3.

See Talker, a TV movie directed by Perry Lang and starring Jay Thomas and Tim Matheson. The film is based on Vallance’s 2005 article ‘The Gippers Ghost,’ the story of the spirit of Ronald Reagan haunting Rancho del Cielo. August 7, 2011.

4.

See Craig Shirley (with Kiron K. Skinner, Paul Kengor and Steven F. Hayward),

‘What Bill O’Reilly’s New Book on Ronald Reagan Gets Wrong About Ronald Reagan:

Bad Sources & Old Misconceptions Persist in Killing Reagan,’

The Washington Post (Oct 16, 2015).

5.

See William Donohue, ‘The Arts: October 13,’ Catholic Leagues Report on Anti-Catholicism (1998 edition).

Jeffrey Vallance was born in 1955 in Redondo Beach, CA. In 1979, he received a B.A. from CSUN and in 1981 an MFA. from Otis. His work blurs the lines between object making, installation, performance, curating and writing and his projects are often site-specific, such as burying a frozen chicken at a pet cemetery; traveling to Polynesia to research the myth of Tiki; having audiences with the king of Tonga; the queen and president of Palau and the presidents of Iceland; creating a Richard Nixon Museum; traveling to the Vatican to study Christian relics; installing an exhibit aboard a tugboat in Sweden; and curating shows in the museums of Las Vegas (such as the Liberace and Clown Museum). In Lapland Vallance constructed a shamanic “magic drum.” In Orange County, Mr. Vallance curated the only art world exhibition of the Painter of Light entitled Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth. In 1983, he was host of MTV’s The Cutting Edge and appeared on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. In 2004, Vallance received the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation award. In addition to exhibiting his artwork, Vallance has written for such publications and journals as Art Issues, Artforum, the LA Weekly, Juxtapoz, Frieze and the Fortean Times. He has published over ten books including Blinky the Friendly Hen, The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978-1994, Christian Dinosaur, Art on the Rocks, Preserving America’s Cultural Heritage, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth, My Life with Dick, Relics and Reliquaries, The Vallance Bible and Rudis Tractus (Rough Drawing). Vallance lives and works in Los Angeles.

Jon Auman is a writer renting in New York; he is a contributing editor with Tenement Press.

with a private vision of pied beauty and sacred banality that extends

to the horizon.

Dave Hickey

The artist Jeffrey Vallance and I spent the worst of the pandemic years working on the project that became Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings. Throughout that time, we rarely went a day without emailing each other. But, for reasons neither of us quite understand, we never spoke on the phone or tried to schedule a video chat. The following interview is thus a record of the first time that we spoke to each other using our own voices. A big thank you to Jeff for suffering through all of my questions and offering us a window onto aspects of his art-making and writing that have received less attention than they deserve.

Auman, MMXXIV

ORDER A COPY OF VALLANCE’S VOYAGE HERE

Jon Auman So, you wanted to ask the first question?

Jeffrey Vallance I remember when you first contacted me, you said you’d been in a used bookstore and found my book [The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978–1994] misplaced or misfiled on the shelves.

You opened it up, and you liked it. Can you explain more about that?

It was a used bookstore in downtown Manhattan. I don’t know why, but in used bookstores I always forget about the Travel section. Then, of course, whenever you go and look at it, you think: ‘Why do I never look at this?’ I think I was waiting for someone, and I’d already looked through all of the other sections. So, I thought I’d look at Travel. I saw this thin spine that said ‘Art Issues Press.’ That rang a bell. It seemed like a weird publisher to have in the Travel section. Then I noticed the title: The World of Jeffrey Vallance. Usually when you see something called The World of so-and-so, it's The World of Jacques Cousteau. I thought, what is this thing? Then I picked it up and looked inside the front cover. The bookstore was pretty dark, and I thought the first page looked water damaged. Then I realized it wasn't water damaged. The book is beautifully printed, and the first page has this very faint image of the Shroud of Turin printed on brownish-yellow paper. Again, I thought: “What is going on here?” I kept flipping through it, and there's stuff about a frozen chicken named Blinky…

Yeah, and it does say ‘Art’ right on the spine. But…

I was very interested in how this book wound up in the Travel section. Maybe someone at the bookstore opened it to one of the essays about Tonga and thought: ‘Right, Travel.’ But, I also don’t think it's out of place in the Travel section.

They could have put it in every other section too.

That was part of what excited me. It’s funny, because a few months later, I went to the same bookstore, and they had the catalogue for the Thomas Kinkade show that you curated, Heaven on Earth, on a table at the front.1

People usually think that my stuff is fiction for some reason. It’s interesting. The fiction thing comes up again and again.

I can see where someone could get confused and think these stories are fictional. I wonder if it has to do with the way you present your subjects. You’re very matter of fact.

Right.

Often, when someone’s writing about a Bigfoot myth, for instance, it’s done in a tone that's very National Enquirer. It’s over the top and trying to be salacious. Whereas, you’re always writing in this specific tone that’s very ... you’re not being sensational. If it’s funny, if there’s humour there, you’re not laughing down at anything.

I think I naturally talk in a kind of deadpan voice. So, maybe that comes through in the writing.

It takes a minute for people to adjust to that tone. When someone first comes to one of your essays, they're thinking, ‘Okay, this is about Martin Luther and his love of working on the toilet.’ Luther is worrying that he’s going to be attacked by the devil while he’s on the toilet. It’s very funny. When you get into the actual research, it doesn’t become less funny. But the reader very quickly realises that it’s not just a gag. You’re talking about actual history.

That’s exactly it. That’s why I like writing about those things. Because it seems so absurd. It’s so incredible. But that’s how it really was. As opposed to what they taught us when I was going to Lutheran school as a kid. They wouldn’t mention anything about that, which would actually have made Luther very exciting for a student, you know? The real story!

It’s similar to when you write about meeting the King of Tonga. You’re always being very respectful to the person. You’re just saying how they were / are. That’s it.

And I ended up liking them better afterwards. After doing the research and doing the writing, I feel like I’ve really made a connection.

How did you start writing these kinds of pieces?

Were you already making art, and then writing is something that came later?

It’s a two step process. Before art, before anything, I liked telling stories, and I liked telling them in a certain way. It’s deadpan, and there is some humour. That was developing, this way of thinking. Then I started doing art. I started doing exhibitions. Much of that early work was very conceptual. At first, the writing was for wall labels. I would write these expanded, paragraph long wall labels that told you what this thing was that you were looking at. It would give some background. Over time the wall labels started to expand. Suddenly it wasn’t just a paragraph, it was a page, and then it was a whole story. I’d have handouts at the galleries. You could pick those up. Then people would ask me if they could publish them. They did end up in travel magazines and art magazines and punk magazines, in all of these different places.

There’s a long history of artists writing, particularly about art. But I struggle to think of other artists who’ve written so much on other subjects. You write a lot about art as well. But you also write about history. You write travel pieces. When you started writing these essays, were you already thinking of it as a project? In retrospect it all seems very cohesive.

When I put The World of Jeffrey Vallance together—the one that you found—I hadn’t considered the writing as a whole body of work. But when it was published, I realised that almost every piece is connected to the piece that came right before it. I saw it as creating this whole. By the 1990s, when I was writing the stuff that's in the second book, Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings, I sort of knew that was happening, that each piece connected to the one before. I just thought, well, maybe one day, if somebody publishes it, there will be these little clues. It was done on purpose. But it would have happened anyway, because I follow where the research goes.

Another aspect that we always talked about when we were working on the book was the importance of specific places. Eventually, it became the organising structure of the book. How does traveling work for you? Do you start with an idea of a place that you want to go?

It’s an entire process in my art. I come up with an idea for a new piece. The genesis is always an earlier piece. Maybe there was one detail from the last piece that becomes the entire new piece. The first thing I do is a lot of research. I try to get every book on the subject, and I read this stuff for years to find out every detail. Then, when I’m ready, when I see the focus of the piece, there’s no more reading that I can do, and I have to go there. Because I know that will be a totally different experience. There’s so much that’s not in books. Even if you read every book, there’s still more. Part of the process is that I always want to meet someone connected to the research. Whether that’s a director of a museum or a priest or the King of Tonga or a psychic. I want to bring in these ultimate experts in whatever field. Usually, I bring them a gift or something, and that induces a certain kind of conversation. So there’s the traveling, and then I come back. I start writing the text and making objects, whatever those are. It might be drawings, or it might be a painting or sculptures or collages or video or a more conceptual piece. I make things based on which medium will tell the story the best.

I think part of what connects the essays is the amount of research you do. You can feel that you know what you’re talking about. But also the voice or the tone that you write in makes it feel like we're seeing different things through the mind of the same person. I’m curious, do you think of that “I” or “Me” as yourself? Do you have a character that you write in? Is it conceptual in that way? Or, do you even think about it?

I don’t really think about it. Because I think of it as myself in that situation. When I’m talking to the King of Tonga, it's just myself talking to him. Afterwards, I try to remember everything we said and try to make some kind of sense out of it. I try to not forget any details. After meetings I go back and immediately make pages of notes. Otherwise something will disappear, some piece of information. People have said that the tone of the writing almost sounds like an encyclopedia, that it's like the voice of knowledge, but with deadpan comedy mixed in.

I was flipping through The World of Jeffrey Vallance, and there's a piece called ‘Blinky, the Friendly Hen.’ In it, there’s a little sidebar titled ‘Chicken Sex Change.’ It says...

It has been noted throughout history that poultry can have an abrupt sex change. In Basel, Switzerland, in 1474, a cock was accused of laying an egg. The cock and the egg were burned at the stake with ‘all the solemnity of a regular execution.’ In Germany, a superstition still exists that a crowing hen should be killed at once or its owner will suffer bad luck. In 1923, Mr. E. Nicholson of Brompton, England stated that during the winter his hen laid eggs, but during the summer it sprouted the comb and wattles of a male bird, starting to crow and trying to mate with hens.

All you’re doing is stating facts. But when you state the actual facts of the situation, they sound completely absurd.

Blinky is a good example of that. That was a long time ago, in 1978. Back then I didn't think about things the way I do now. With the Blinky piece, everything was spur of the moment. Oh, here's an idea, I'll bury a chicken! Okay, I'm gonna go do it. And now I'm doing it. Then there it is. It's buried, and it’s over. So, I never thought about the meaning of it, or why I did it, or why did I choose certain symbols or certain ways of doing things? I wasn’t thinking about any of that at all. When I wrote the piece that you just read from—which is from at least 10 years later—I realised that the whole Blinky saga was kind of like I was acting out a pre-existing myth. All the steps that I took, that I thought were purely random, were related to different rituals and myths from around the world involving the chicken. It really made sense in hindsight. It was shocking to me that I was acting out all of these different rituals from different lands and different times, without knowing that I was doing it. It was really powerful and spontaneous, and I could see that it was connected to this whole body of work.

There’s a piece in Voyage to Extremes that’s basically you going through all of these different instances where the chicken is used as a symbol by different faiths and different cultures from all around the world. When you read that piece and then you go back and look at Blinky, there is something really profound there. This frozen chicken seems to have a limitless potential for meaning. You could ponder it forever. It happens again and again in your work. You start with something like a frozen chicken in a supermarket in a suburb somewhere, and it doesn’t take long to get from that point A to a point B that’s dealing with the sacred and / or the profane. Dave Hickey talks a lot about Raymond Chandler in his introduction to The World of Jeffrey Vallance. He says your essays are like mysteries, and that you’re the detective jumping from one clue to the next. I think he’s right. At a certain point, like in a lot of good crime novels, the desire to find out who the murderer is falls away, and what’s left is the pure pleasure of description and making connections. Is it strange to go back and think about these older pieces again? Some people hate looking back at anything.

That’s another huge question. I can only answer the tip of it. When you mentioned the word strange... The example that I think of is the ghost story about Nixon. The first version of it was very short, like a paragraph.2 I actually went to the Nixon library. The essay was about how I would feel if there was a ghost, and what the ghost would do. It wasn’t saying that this was true, but it seemed likely, so I wrote the story. Then, somehow, it got on the Internet. These two guys, Joel Martin and William J. Birnes, wrote a book called The Haunting of the Presidents about the ghost stories for every president. Of course, they had Nixon. Their Nixon story was based on my paragraph. It was really obvious because they basically took every sentence from my story and expanded each one into several paragraphs until they had two chapters. But, that wasn’t the weird part. At the end of every ghost story, there was a section where the authors hired a psychic that would channel the president and then ask him if the ghost story was true. They did that with Nixon, and the ghost of Nixon said the ghost story was completely true. When I was reading this, my eyes were bugging out. When you have the actual ghost say the story is true... But that wasn’t even the strangest part! So the ghost of Nixon is talking, and then all of a sudden the ghost goes on this tangent. It starts talking about the writer of the original ghost story, and you could very clearly tell that it was talking about me. It couldn’t be anyone else. It was talking about how the writer collects Nixon stuff and was part of the campaign—all sorts of stuff, and all these facts. My eyes were really bugging out, but it was great. It's like Nixon's ghost pulled a prank on me. It was as if the ghost said, ‘If you're going to pull a prank on me, then I'm going to prank you back.’ I love when the stories go in that direction.

When did you become interested in the paranormal? It comes up again and again in your work.

When I was a kid I was really fascinated by The Addams Family TV show. I didn’t really know what it was about or why I was attracted to it. But I realised later that I wanted to be in that family. They were all weird people doing weird and outrageous stuff. But it felt normal to me, like I'd found a normal family that I could be a part of. The Addams Family opened up a lot of stuff. Monsters in general. Hot rods and monsters like Rat Fink. It started this whole lifetime of interest in weirdos and monsters. Then, around 1977, I read the works of Charles Fort. He was this guy that collected newspaper clippings about all of this totally weird shit. Every kind of paranormal thing. He was kind of like the father of all things paranormal. He was the first person to talk about different concepts that we now take for granted. He was also very funny and very deadpan. And he lists a lot of facts. So, it's really those two authors: Charles Addams for monsters and Charles Fort for the paranormal.

I’m curious how people in the art world responded to you putting these kinds of things in your work. It’s making me think of that time—how many years ago was it?—when they found that big metal obelisk in the desert and no one knew what it was or who had made it. Someone started a rumor that it was a John McCracken sculpture that he'd made to communicate with UFOs. Something like that. I feel like people in the art world are very uncomfortable with talking about things like UFOs. They like John McCracken, the nice minimalist sculptor, and want to leave it at that. I thought it was fascinating, and McCracken was very interested in UFOs.

I love stuff like that. That’s what I live my life for. When these two unrelated things suddenly come together and create a new body of knowledge. I always thought it was odd that I'd write these things that are totally paranormal, then they’d publish them as articles in art magazines. I wasn’t writing art criticism or anything, but somehow it fit in an art magazine. I don’t know how that's possible. Then, when the art museums and art magazines stopped wanting to do that, I started writing for Fortean Times, which is a paranormal magazine. But I often find myself writing about art there, in a paranormal magazine.

I was thinking about the research that you do for these pieces. Are you the kind of person who, once you’ve researched something, you file it in the back of your mind and revisit it? Or—when you're done with a subject—are you done with it forever?

I’m never done. Ideas can always spring up again suddenly and connect to something else. Out of nowhere they can take on this new life. I think that’s why the stories connect. It’s like with the Blinky story. There’s two major stories. There’s the original piece, and then the second one came from reading the Bible. There’s one passage that really got me. It’s Jesus talking about himself. He compares himself to a mother hen with her chicks. Immediately, I thought about all of these other images of Jesus, like the dove and the lamb of God. No one wanted to take on Jesus as a chicken. But, he compared himself to one! So, I thought: ‘Isn't this an important idea?’ So that’s where one of the later texts comes from. When I did more research, I realised that it’s in every religion—shamanism, Buddhism, Islam. The symbol of the chicken is central, yet no one ever talks about it. I did more research and found out that the area Christ was living in was, at that time, the poultry capital of the Earth. Of course, he knew about chickens! They were everywhere. It totally makes sense. He didn't choose the image of the chicken at random. It was something he saw every day.

You see that throughout the Bible: snakes, dusty mountains, the red sea with some boats on it. There are big, miraculous events that happen, but a lot of the Bible is obsessed with quotidian, everyday life. There are a lot of rules and regulations for the most mundane things. To change the subject slightly. Are there writers who were important to you when you were starting to write?

Herman Melville. Especially Moby Dick and its obsession about one thing, about whales. Melville goes on all of these tangents about Whales, then he comes back to the story. That was really important. This singular idea that you can expand on. A lot of what I read aren't novels. I read a lot of scientific manuals on different subjects, like on chickens or anthropology. I love to get books related to what I'm thinking about. With Melville, I loved all the details. Another one is Joseph Campbell. Maybe I like all of these things that take an idea and expand on it, and then connect it to other things along the way.

It allows you to talk about a lot of different subjects from an angle that doesn’t feel too aggressive. I don’t think of your essays as aggressively ideological. You write about heads of state that you meet. There’s the Marion Barry piece. But I feel like you’re letting these people speak for themselves.

I like to do that because you could start off saying you either hate this person or you like this person, and then make that the basis of what you're writing about. But, I would rather let people find that out for themselves in the writing. One example of that is the story I wrote about Ronald Reagan's ghost. It's been written about extensively by right-wing writers, like Bill O’Reilly in Killing Reagan. At some point they adopted the ghost of Ronald Reagan and made it their champion. They made it a part of their philosophy. There was even a TV movie, called Talker,made about it.3 For me, all of it becomes a part of the story. I just hope that people can pick up on how absurd that is, that they've taken this story completely literally. At some point, they started to be criticised in the Washington Post for talking and writing about the ghost too much.4 That’s perfect. There's this whole domino effect.

A lot of your pieces have these very interesting afterlives. You’re writing about myths, about stories that are being passed down through time, about how they change and become distorted or renewed or inverted. With the Reagan ghost story you can see that taking place in real time. You can see how this small thing that you wrote is taken up by other people who create this new, absurd context for it. You see the actual process of how myths are made. And then these crazy loops start to happen.

Right, loops happen. Then it totally gets out of control. Like with the Nixon story, where it loops back to me and I’m pulled back into it in some bizarre way.

The figure of Nixon comes up again and again. What is it about Nixon—and also Reagan—that fascinates you?

Well, I think part of it is that I was of a certain age. With Nixon, I was a preteen so it made a special impression. All my life I’ve been obsessed with politics. In the past, I guess I had seen politics in a neutral way. I would go to rallies, but I would go to rallies for both sides. I would collect things like buttons and political banners from both sides. It was like documenting history at a certain point. Of course, because of Vietnam and then Watergate, Nixon was the president that I most loathed. I think Reagan was next in that line. I had this philosophy about both Nixon and Reagan, that when they died they were over, like they were immovable and fossilised. Then I thought that writing about their ghosts would continue that history or keep it moving, even though they were gone. You could add more information about them. Which I did for myself. I didn't realise that other people would also pick up on that and start doing it. I saw it as writing another chapter in their histories. You can read these whole biographies about Nixon from birth to death, but then the book stops. But, I thought, ‘No, you can continue on!’ I could write about what their ghost does and how people interact with the ghost.

You’re documenting how a strange fragment that someone said or wrote—or a real, physical fragment, like the Shroud of Turin—lingers through history. With the Shroud of Turin, this is a thing that was draped over someone's body at some point. It was just a cloth. But somehow this cloth has made its way through history. These objects are also kind of like ghosts.

It's all a bit like a ghost. They continue to play a part in people’s lives. I did want to speak about the Shroud... I spent some time in Turin in 1992. I was doing research on the Shroud, and while I was looking at it I found that there were these images of clowns on it. Of course, they were actually the scorch marks from when someone tried to burn the shroud. I wrote about it and presented it like evidence. I mean, in a way, it seems like the most mocking thing you could do. To say ‘Oh, I found clowns on the Shroud.’ But, when you actually look at the research, it totally makes sense. In terms of: if this is a true relic, then who would want to burn it? Obviously, that would be Satan. But Satan didn’t completely burn it. He failed. But he did manage to burn these clown-like self-portraits of himself onto it. I did more research, and in the Middle Ages, clowns were more like a trickster demon, which takes you back to the devil. That project got me in trouble with this group that puts out a yearly report.5 It’s a pamphlet where they list everything that they think is anti-Catholic. They found my column on the Shroud of Turin and thought it was anti-Catholic. So I wrote to those people and told them my whole theory. Then they said, ‘Oh, we understand. We see your point. We'll take you off the list.’ That was when the whole piece became perfect. It’s totally outrageous. There’s clowns on the Shroud! At first it can seem mocking. But if you blame it on Satan, then it totally makes sense again. Now that research reverberates through the groups of people that do research on the shroud. They can’t avoid it. All of these things that I research somehow seep back into the pool of research, which I love. The piece becomes part of the thing itself.

This is making me think of another piece in Voyage to Extremes. It’s the one where you’re writing short descriptions of different sites around Las Vegas. One of the things you describe is a Weeping Virgin Mary statue in someone’s backyard. It’s the kind of thing that anyone who’s grown up in the US is familiar with. Especially pre-internet, you’d always see stories on local TV news. Someone buys a block of cheese and finds the image of George Washington’s face on it. Or, they see the Virgin Mary burned onto their toast at breakfast. Sometimes when you’d see the image of the block of cheese you’d think, ‘Wow, that really does look like George Washington!’ But you’d snicker at it. In your piece, you describe details like that the statue is in this guy’s backyard. You give the opening hours for when you can visit it. It’s very funny. But then, when you put that piece in the context of your other pieces about the Shroud of Turin... The Shroud is taken seriously by millions of people around the world. But you write about the Shroud and the Weeping Virgin in the guy’s backyard in the same way. You don’t treat one as more sacred or more ridiculous than the other. Doing that makes us think about both of them differently. We start to think about the Weeping Virgin as a cultural relic that people agreed to imbue with meaning. And it also makes us realise that, at some point, the Shroud must have been a funny thing in someone’s backyard. I’m curious how you get this effect. Is it all about the research? You don’t seem to be bringing many preconceptions to these subjects.

It’s about the research. Let me tell you a story about seeing the Weeping Virgin. Somebody told me about it. I think it was in the local newspaper in Vegas. I went to see it. I called to make sure the owners were going to be there since it was in their backyard. When I went out there, it was something like 110°. It was really hot, and the shrine was open to the air. I just expected to look at it. I thought I was going to see this Weeping Virgin, but obviously it wasn't going to be weeping. But, while I was standing there it started weeping. The people that owned it rushed up with cotton balls, soaked up the tears and gave those stained cotton balls to me. So, I had those relics of the Weeping Virgin. I had the weirdest feeling while I was standing there. I figured it was one of two things: either it really was a miracle, or I was being completely tricked. I saw both of those possibilities as equally interesting. It was fantastic. Either way it was fantastic. If they were trying to trick me into believing it was weeping—that's still weird, almost just as weird as a miracle. I had a profound reaction to that. It was a real reaction. I was there. I saw it. Something was happening there. Possibly it was a fraud, but wouldn’t that be interesting too? I’m not saying it was a fraud, but it could’ve been.

Even if you think something like the Shroud or the Weeping Virgin or Bigfoot sightings are completely absurd, the fact that human beings have invested so much time and energy in these ideas is just as fascinating. I do think there’s something about the way that you approach these subjects that makes them accessible to anyone. It’s fascinating that these pieces have circulated in the art world. Obviously so much of art history consists of religious art, but having serious discussions about religious and paranormal topics is pretty rare in that world. The way you write about these subjects seems to allow people to approach them from a different angle. There is something magical about it. A little bit like what you were saying about when you were standing in front of the Weeping Virgin: it allows people to have a real reaction. You disarm their preconceptions.

Well, I agree with you that it's a magical thing. And I’ll take that one step further. I think that all life is a miracle, even the most mundane things. I mean you wake up and everything is the same, and then all of a sudden it's not. The mundane-ness of something makes it into a miracle. If you look at it a certain way, the simple fact that we're alive on this planet is insane. You just have to take a moment and really look at it and you realize everything is a miracle.

That’s exactly what I get from the book. You’re fascinated by everything. It’s a voracious appetite for the things that people do, how the world works, and how it doesn’t work sometimes.

And I don’t want to judge it. I don’t want to tell you what you should believe. I want you to make up your own mind by reading the story. I’m sure people can read these things and come away with different ideas and interpretations.

Part of why I think it was important to collect these individual essays together is that they create even more, and sometimes different resonances when you read them side-by-side. The book has an arc to it. We end up at this sequence of essays about Thomas Kinkade.

Kinkade is a perfect example. In a way he’s a living embodiment of this country’s divisions. He was divided within himself. There were some people who saw him as being like a saint, almost like a Christ figure. They would look at his paintings and receive miracle healings from them. I don’t make fun of that because I believe people really believe it and did get some healing from it. But at the same time, Kinkade always knew that he had a dark side that nobody else knew about. He knew that he was sort of a fuck up. So what do you do with that? People are ascribing miracles to your paintings, but you feel far from perfect. I think it did a number on his head.

In one of the last essays, you talk about his secret alter ego, a demonic, leather-clad biker named Ed Aknik ["Kinkade" spelled backwards], that he’d invented for himself. It reminds me of what you were saying earlier about Martin Luther. Finding out about the other sides of these people can actually make us feel closer to them.

It makes him into a real person. Because the other person we’d seen had become a corporate mascot with the name Thomas Kinkade. That Thomas Kinkade wasn’t real. In retrospect, though, it all makes sense. Here’s this young guy who's painting these paintings that look like they're from the turn of the last century. He’s painting these cottages. They’re not hip at all. He’s selling them to senior citizens, housewives, people in the Midwest. It became an empire. You couldn’t do all this stuff and not have some other mode of expression. But again, when I did that show, I had no evidence.

This theme emerges at the end of the book—maybe ‘theme’ is the wrong word—about things that are buried underneath. Actually, this is a good topic to finish on. Recently, someone showed me pictures and videos taken by someone that’s currently working with a team of people who are restoring the Mike Kelley piece that is mentioned in the last essay in the book. The piece is this ranch-style house in Detroit that’s modelled on Kelley’s memories of his childhood home. Underneath the house there are these seemingly infinite layers of underground rooms, hallways and ladders that aren't accessible to the public.

Like psychological layers. Like layers of the mind.

Voyage to Extremes ends with a description of that piece. It’s an incredibly affecting ending for me. I don’t know why exactly. The book is so filled with humor. It’s so pleasurable to read. But, there’s something about the ending that makes me look back across the rest of the book in a different way. There’s a lot of laughter, but also something serious going on.

I think it’s that I take everything seriously, and I find humor in everything at the same time.

NOTES

1.

See Jeffrey Vallance, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth,

published by Last Gasp (April 2004).

2.

See Jeffrey Vallance, ‘I am not a Corpse (Nixon’s Ghost),’

L.A. Weekly, Sept 30 / Oct 6. (1994).

3.

See Talker, a TV movie directed by Perry Lang and starring Jay Thomas and Tim Matheson. The film is based on Vallance’s 2005 article ‘The Gippers Ghost,’ the story of the spirit of Ronald Reagan haunting Rancho del Cielo. August 7, 2011.

4.

See Craig Shirley (with Kiron K. Skinner, Paul Kengor and Steven F. Hayward),

‘What Bill O’Reilly’s New Book on Ronald Reagan Gets Wrong About Ronald Reagan:

Bad Sources & Old Misconceptions Persist in Killing Reagan,’

The Washington Post (Oct 16, 2015).

5.

See William Donohue, ‘The Arts: October 13,’ Catholic Leagues Report on Anti-Catholicism (1998 edition).

Jeffrey Vallance was born in 1955 in Redondo Beach, CA. In 1979, he received a B.A. from CSUN and in 1981 an MFA. from Otis. His work blurs the lines between object making, installation, performance, curating and writing and his projects are often site-specific, such as burying a frozen chicken at a pet cemetery; traveling to Polynesia to research the myth of Tiki; having audiences with the king of Tonga; the queen and president of Palau and the presidents of Iceland; creating a Richard Nixon Museum; traveling to the Vatican to study Christian relics; installing an exhibit aboard a tugboat in Sweden; and curating shows in the museums of Las Vegas (such as the Liberace and Clown Museum). In Lapland Vallance constructed a shamanic “magic drum.” In Orange County, Mr. Vallance curated the only art world exhibition of the Painter of Light entitled Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth. In 1983, he was host of MTV’s The Cutting Edge and appeared on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. In 2004, Vallance received the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation award. In addition to exhibiting his artwork, Vallance has written for such publications and journals as Art Issues, Artforum, the LA Weekly, Juxtapoz, Frieze and the Fortean Times. He has published over ten books including Blinky the Friendly Hen, The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978-1994, Christian Dinosaur, Art on the Rocks, Preserving America’s Cultural Heritage, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth, My Life with Dick, Relics and Reliquaries, The Vallance Bible and Rudis Tractus (Rough Drawing). Vallance lives and works in Los Angeles.

Jon Auman is a writer renting in New York; he is a contributing editor with Tenement Press.