Rehearsal / 49. Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by Sean Wilsey

![]()

Luigi Pirandello, photographed during a visit

to Finland, 1933 (Suomi, Helsinki).

An excerpt from a novel,

One, None, and a Hundred Grand

translated from the Italian

by Sean Wilsey.

![]()

Translated from the Italian by Sean Wilsey

Luigi Pirandello, photographed during a visit

to Finland, 1933 (Suomi, Helsinki).

An excerpt from a novel,

One, None, and a Hundred Grand

translated from the Italian

by Sean Wilsey.

The Destruction of a Maggot

‘What're you up to?’ my wife inquired, as she watched me hover uncharacteristically before the mirror. ‘Nothing,’ I replied. ‘Or just looking up my nose. Inspecting this nostril. Pressing on it brings out a little hint of pain.’

‘Ha,’ she laughed, ‘I thought you were trying to figure out which way you lean.’

I wheeled on her like a dog with a smashed tail.

‘I lean? Like, I'm off-plumb…? Nasally? Me?’

‘Mmm-hmm, darling,’ came the better half’s smug reply. ‘Take a good look at yourself. You lean right.’

I was twenty-eight years old and till then had held my nose to be, if not beautiful, at least wholly inoffensive, in keeping with the rest of me. And I found it easy to sustain the conviction—like most people lucky enough to inhabit a serviceable body—that it's ridiculous to be vain about your features. So the sudden and surprising discovery of this flaw pained me like an undeserved punishment.

I guess my irritation offered my wife some sort of an in, because she quickly added that if I'd been placating my ego with the delusion that I was flawless she would see to it that I was set straight, since when it came to a rightward tilt my nose was scarcely a solo actor.

‘So there’s more? Like what?’

‘Ha, more.’

I’m all for wives. But my sense of self was—you’ll indulge me—vulnerable to collapse, at the least critical utterance, with each fly I saw buzz by, into a morass of doubt and second guesses.

Oh, you say, you’ve got a lot of time on your hands.

No, not when you consider my constitution. Were it not for that, yes. And I do do my fair share of loafing. I’m rich, with two trusted friends, Sebastiano Bottomline and Stefano Sly, who've seen to my affairs since the death of my father. But returning to the subject of tiny corporeal defects, they took on significance, all of them, suddenly, with the realisation that their presence implied—was it possible?—that I did not know my own body; the components that comprised the most personal expression of myself: nose, ears, hands, legs.

![]()

‘A maggot in an arable field,’

annotated etching, date unknown,

℅ the Wellcome Collection.

And from that moment forward I began to pursue myself with the desperate objective of rooting out the fugitive stranger within me; one of the side effects of this objective being that I was incapable of standing in front of a mirror, since the reflection would immediately become the me that I knew instead of the one who lived in others, whom I could never know; the one others saw living his life and I could not see.

Let me restate that at the time I believed that this stranger was singular: one man to all others, just as I believed myself to be one man to myself. But soon my atrocious drama would complicate itself: with the discovery of a hundred thousand men all with that single name, Moscarda—Maggot: hideous to the point of cruelty, a name that wasn't merely me to others but also to myself, all of them living inside this poor body of mine, which itself was but one, one and none, alas, if I stood before the mirror and looked fixedly and unblinkingly into my own eyes, abolishing as I did so all feeling and will.

Maggot. Destined to become a fly, with its sour, spiteful, annoying drone.

But my spirit was nameless and unbound, alive within a vast interior landscape; and whenever my name was mentioned, I didn't even notice, occupied as I was with all the things that I saw inside myself. But for other people I wasn't whatever nameless, integral-yet-varied world I carried around within. Instead I was part of their world, outside myself, detached, one, alone, a miniscule and persistent feature of a reality beyond my control, an externalised being belonging to others, known as Maggot.

‘Gumdrop,’ my wife said. (Having taken Vitangelo, which, alas, is my given name, and made this nickname out of it.) ‘Aren't you worried that Anna Rosa might be ill? She hasn't let anyone see her for three days and the last time she was here she had a sore throat. Know what, Gumdrop? It's been four days. Now it’s undeniable: Anna Rosa's ill. I’m off to check on her.’

I begged her not to spend too much time with Anna Rosa, especially if her friend was sick with a sore throat.

‘A quarter of an hour, no more. I promise you.’

Which guaranteed her absence till evening.

I spun on my heel, rubbing my hands together for joy.

‘At last!’

And I began preparing myself, waiting till every trace of joy and anxiety disappeared from my face, as, inside, I extinguished every last spark of feeling and thought in order to be able to comport myself before the mirror in a fashion that might permit my body to disengage from my self and be put on view.

‘Here we go!’ I declared. ‘Showtime!’

Then I stepped forward, eyes closed, hands groping. As soon as I felt the top of the dresser I came to a standstill and waited, eyes still lidded, filled with the most absolute inner calm, the most total indifference.

Until a voice spoke up, informing me that he was also there in the mirror, the outsider. He was waiting, like me, with his eyes shut. He was there, invisible.

He couldn’t see me, either, because, like me, his eyes were closed. But what was he waiting for? The sight of me? No. This guy could be seen, but he couldn't see. For me he was what I was for others, a thing that could be seen but could not see itself. But, upon opening my eyes would I see him as another would see me?

This was the goal.

I opened my eyes. What'd I see?

Nothing. I saw myself. There I was, frowning, burdened by my usual thoughts, with a thoroughly disgusted expression on my face.

I was so consumed with prideful rage that I felt a temptation to spit in my own face. But I held myself in check, smoothed out the creases, softened the gaze; until lo, bit by bit, as I mastered myself, my reflection dulled and seemed to recede; so I stepped back, too, and almost lost my balance; and my face suddenly affected a smile.

‘Be serious—imbecile!’ I screamed at him. ‘This is no laughing matter!’

And the alteration of my expression in the mirror, in keeping with the spontaneity of my outburst, was so sudden and was followed with equal immediacy by a deflated hopelessness, that I succeeded in observing my body, detached from my imperious spirit, there, before me in the mirror.

Ah, at last! There it is!

Who?

Nothing. No one. A poor mortified body waiting for someone to take it away.

After a long silence I muttered, ‘Maggot…’

‘Two maggots,’

etching, date unknown,

℅ the Wellcome Collection.

To be demolished, it’s necessary to exist; but in order to be replaced it’s necessary to exist, and to be seized by the shoulders and pulled back, so that a copy may be put in your place.

My wife, Dida, neither razed nor replaced me. It would’ve seemed to her, on the contrary, to be a demolition or a substitution were I, rebelling, and in the course of affirming a will to live in my own way, to cut off her Gumdrop at the kneecaps. I doubt she knew her Gumdrop any better than I knew him! It didn’t matter that he was her creation! He still wasn't a puppet. If anything I was the puppet.

Because while Gumdrop existed for her, I didn't exist at all, and never had.

To her I existed solely as Gumdrop, her creation, whose thoughts and feelings and tastes—though in no way my own—I could not so much as fractionally alter, without running the risk of suddenly becoming a stranger she wouldn’t recognize, a stranger she wouldn’t be able to understand or love.

Once in a while I came upon her in tears at some misery for which Gumdrop was responsible. Yes—him!

And if I asked her:

‘Darling, come, what’s the matter?’ she replied: ‘You're asking me? As if it could be anything other than what you just said?’

‘Who, me?’

‘Yes, you—obviously!’

‘But wha-? What?’

I was flabbergasted.

It was clear that there was no correlation between whatever I thought I was saying and whatever she heard Gumdrop saying. Statements that would have been harmless coming from me, or anyone else, made her weep when spoken by Gumdrop, because in Gumdrop’s mouth they held a mysterious significance; and left her in tears.

When Dida was a girl she arranged her hair in a style that pleased me a great deal. Once we were married she abandoned it. Thinking I should let her do as she liked I never told her the new style really wasn't to my liking. Then one morning she stood before me in a bathrobe, a comb in her hand, radiantly coiffed as before.

‘Gumdrop!’ she purred, thrusting open the door to her dressing room to expose herself with a peal of laughter.

‘Oh!’ I exclaimed, staring in dazzled admiration. ‘At last!’

And she immediately thrust her hands into her hair and yanked out the combs—demolishing everything in a split second.

‘Ha!’ she laughed. ‘I got you. I know darn well how you much loathe my hair that way, Mister!’

‘Dida, darling!’ I objected vehemently. ‘Who told you such a thing? It’s the opposite, I swear to you!’

‘Ha, ha!’ she repeated, covering my mouth with a hand. ‘You’re just saying that to flatter me. I don’t need you to flatter me, my dear, or act as if I don't know how my Gumdrop likes it best?’

And off she ran.

Do you hear what I'm saying? She was so convinced that Gumdrop preferred her hair in a manner we both despised that she kept it that way. She sacrificed herself for Gumdrop’s desire. You think that’s nothing? Isn’t that the most profound and genuine of sacrifices?

Oh, she loved him so!

And now that this situation was finally coming into focus I was starting to feel—don’t laugh!—incredibly jealous! Not of myself, of course—how could I be jealous of myself, dear readers? I was jealous of someone who wasn’t me; of an imbecile who had inserted himself between my wife and me; but was no vain shadow, no, I beg you to believe me—because, on the contrary, this guy made a vain shadow of me—me, me; appropriating my body for himself and using it to make love to her.

Think about it. Wasn’t my wife using my lips to kiss someone who wasn’t me? My lips? No—not mine! How were they mine, properly mine, these lips she was kissing? Sure it was my body in her arms. But to what degree was that body truly mine; in what way did it truly belong to me if I wasn't the one whom she was embracing and loving?

Just consider it. Wouldn't you feel your spouses were betraying you with the most refined treachery if you discovered them grasping in their arms, tasting and delighting with their bodies, a fantasy-other, with whom they had replaced you in their hearts and minds?

How was this different from my situation? My situation was even worse! In the former scenario your spouses, if you’ll pardon me, in the fullness of their falsity, were only fantasising about someone else; while in my case, mine was actually holding in her arms the physical form of someone who wasn’t me!

‘A horse fly (Tabanus dorsivitta),’

pen and ink drawing by A.J.E. Terzi, ca.1919℅ the Wellcome Collection.

I’d never separated my father from my paternity. And when remembering him as a father I’d always thought of him as what he was for me; practically nothing, really, since my mother died young and I got sent to a boarding school far from Oncemoney, and then another one, and then a third, where I stayed till I was eighteen and went to college, where I spent six years flitting from one subject to the next, without acquiring practical skills in any of them; till I was finally summoned back home to Oncemoney and—whether as reward or punishment I'm not sure—immediately betrothed. Two years later my father died without leaving me any sense of who he was, or the depth of his affection, just that vivid memory of his tender smile, that was part pity, part derision.

But who had he been in his own mind? Now, as I started to see who he’d been for others—while being so little for me!—my father began dying all over again. And that smile he gave me also came from others, of course, from his awareness of how others saw him.... Now I understood it, what it meant, and it was horrible.

In boarding school my friends were always asking me, ‘What does your father do?’

And I'd say: ‘Banker.’

Because, for me, my father was a banker. And a banker, as I know well, progresses in his percentage from ten to twenty and from twenty to forty, while his hometown's disdain at the infamy of his usury slowly, simultaneously grows, until tomorrow it'll weigh shamefully upon the son who wanders about with his strange thoughts, a pathetic trophy of the father's success, meriting, trust me, that smile of tenderness, part pity and part derision.

Consumed by these thoughts, eyes wide in horror, but the veiled horror of dejection, I went and stood before my wife Dida, my sadness plastering a pointless smile on my face, born of the suspicion that no one would ever be straight with me.

I remember finding her in a luminous, sunlit room, dressed in white, wreathed in brightness, arranging her new springtime wardrobe in a gargantuan, white-lacquered, triple-gilded armoire. Reeking of secret shame I searched inside myself for a voice that wouldn't seem too strange, and said: ‘Hey, uh, Dida, you know my profession, right?’ In her hand was a discoloured wedding dress, dangling from a hanger, and when she turned to look at me it was like she couldn't remember who I was.

Confused, she repeated, ‘Your profession?’

And I had to rebreathe the reek of shame, and, the words like a whip lashing my spirit, repeat the question that hung in the air. It fell to pieces in my mouth this time.

‘Right,’ I said, ‘What is it that I do?’

Dida paused for a moment, fixed me with a stare, then burst out laughing.

‘But what are you talking about, Gumdrop?!’

And with that explosion of laughter my horror, the blind nightmare of need that consumed my questioning spirit, was demolished.

Because I could suddenly see who I was—a usurer and a fool; the former in the street and the latter with my wife, Dida. For whom I was Gumdrop, a specific flavour of Gumdrop; though who knew the variety of other flavours I brought forth on the palates and in the souls of our town. While all the while my soul was indifferent, free and untouchable inside of me, in its intimate place of origin, beyond concerning itself with the things that preoccupied me, that had been brought into being and left to me by others; money and the labors of my father.

You disagree? Whose burden is it then? Even if I could ignore the revolting reality imposed upon me, I still had to recognise that whatever alternate one I gave myself, of my own accord, would not, alas, be any more true, or real, than the ones that others gave me, the ones in which others had confined me inside a body that now, in front of my wife, did not even seem to me to be mine, given that it had been appropriated by this Gumdrop of hers, who just now had uttered a new inanity at which she was chuckling so heartily.

‘You’re asking me your profession! Why don't you know that yourself?’

‘Trophy of success...’ I said, almost to myself, my voice emanating from a silence that seemed to originate in the beyond. Standing like a shadow before my wife, no longer knowing from whence I—I mean I myself—was addressing her.

‘What did you say?’ she repeated, from the solidity of her perspective as the bearer of a discoloured wedding dress.

And when I failed to respond she came towards me, took me by my shoulders, and blew into my eyes, as if she were extinguishing a look that didn’t belong to Gumdrop, at least not the Gumdrop she knew, the one who, like her, pretended not to not know what people in town said about my father and what he’d done for a living.

Wasn’t I worse than my father? At least my father had worked…. While I! What did I do? The faithful son. The faithful son who spoke of strange (and otherworldly) things, like the other face of the moon, or his discovery of a nose that leaned to the right, while the so-called Bank of My Father was administered by two faithful friends, Sly and Bottomline, who labored dutifully that it might prosper.

Why hadn’t they killed me by then? Well, readers, they hadn’t killed me because I had not yet stepped away from myself in order to see myself; I still lived blindly under the circumstances in which I had been placed, without considering what they might be—this was how I'd been born and grown up and it was just the way things were; much as other people had grown accustomed to my lifestyle and manners; because they’d known me this way; they couldn’t think of me otherwise, and as a result everybody could just about look at me without hatred, and even laugh at the faithful son.

Everyone?

Suddenly I was pierced in my soul at the memory of four eyes, two sets of poisoned daggers: belonging to Marco Godson and his wife Diamond, the couple I encountered each day on my street coming home.

That trophy of success I mentioned earlier. Yours truly was not the only one. My father awarded himself numerous others by funding, with boundless munificence, all the while wearing that condescending smile of his, the undying illusions of people like Marco Godson, who'd tracked him down in order to decry the lack of means with which to realize his designs, his dreams: riches!

‘What'll it take?’ my father asked.

‘Oh, hardly anything.’

Because the amount that would suffice for them to become rich was always a trifle. And my father would pitch in.

‘That’s it?!’ he’d say when asked for such a modest amount.

‘Well. I must've made a mistake crunching the numbers before. But this time, for sure...’

‘So how much?’

‘Hardly anything!’

And my father kept coughing up. Until he’d had it. Which is why it's easy to imagine how, after being cut off, there was no upwelling of gratitude towards the man who chose not to savor, down to the very last drop, the utter futility of their dreams; which suited them fine, enabling them, as it did, to remorselessly blame the failure of their illusions on him. And no one could have avenged himself with greater persistence than Marco Godson, by branding my father a usurer. He was the most dogged of all. But now, following the death of my father, and not without reason, he’d turned his ferocious hatred upon me. Not without reason, because I, too, almost behind my own back, had continued to sponsor him. By permitting him to live, rent free—Sly and Bottomline never asking for a penny—in a shack on some land I owned. A shack that would provide the precise means to employ him in my first experiment. Because if memory serves Marco Godson and his wife Diamond were fated to be the first of my victims, that is to say the first to take part in the experiment of a Maggot's destruction.

Just for fun, would you like to perform this experiment together—yes or no? I mean shall we pierce the skein of reality in order to partake in the terrifying joke that lives beneath the placid exterior of quotidian interactions, beneath the plain appearance and so-called solidity of all the most run-of-the-mill and normal-seeming people? The joke, dear God, that every five minutes infuriates and compels you to shout at whichever friend is at your side:

‘Look! How can you not see this!? ARE YOU BLIND!?’

No, they don’t see, because they see some other thing when you think they should be seeing what you see; reality as it appears to you. They see what seems real to them; and the way they see it you’re the blind one.

I’m dissecting the joke because I’ve finally gotten it.

‘The older larva of the fly (Dermatobia cyaniventris),’

coloured drawing by A.J.E. Terzi, ca.1919℅ the Wellcome Collection.

In order to put my plan into motion I headed straight to the office of Stampa the notary, at 24 Crucifix Street. This being (these are incontestable facts) a specific day… in a specific year… in the r

eign of Victor Emmanuel III… the place where—by the grace of God and the dispensation of said King-of-Italy, in the noble city of Oncemoney, at Civic numeral 24, Crucifix Street—the royal notary Signor Stampa, a guy around 52 or 53 years old, kept his offices.

As I entered his office burdened with these reflections you can just imagine the raucous laugh that burst out of me when I saw him there before me, so stolid and serious, poor thing, Signor Stampa, notary, clueless to the fact that the man inside of me might be someone other than the man he saw; while being absolutely sure that he himself was just who he thought he was, for me—the very same man who knotted his tie before the mirror each day surrounded by so many familiar and reassuring comforts.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘Here I am, Signor Notary. And if you'll pardon the question, are you always here, enveloped in this silence?’

He squinted at me:

‘Silence? What do you mean?’

At that moment Crucifix Street was an unmitigated cacophony of buses and pedestrians.

‘No; obviously not in the street. But what about all the documents here, Signor Notary, behind the dusty glass doors of these bookshelves. Can you hear them?’

He began to look at me in a peculiar way, this notary, a way that made me think it might be prudent to leave the subject of noise alone and avoid compromising the experiment; for which—both in principle and in particular, there, in the presence of the notary—it was necessary that zero doubt arise as to the soundness of my faculties. So I asked the good notary if he knew of a certain house situated in a certain street with a certain number; property of Mr. Vitangelo Maggot, son of the late Francesco Antonio Maggot…

‘Isn’t that you?’

‘Yes, me,’ I hastened to tell him. ‘That’s me, Mr. Notary. And you shouldn’t have any difficulty in confirming that the house is mine, just like the entire inheritance of the late Francesco Antonio Maggot… who was my father, right? Right! And confirming the fact that this house is vacant now, Signor Notary. Small, of course… five or six rooms, spanning two little parcels. Is that the right way to put it? Parcels, great. So, it’s vacant, Mr. Notary; available for me to dispose of as I see fit. And so, you…’

Here I knelt down, with great solemnity, and in a low voice confided in Mr. Notary the specifics of the act that I intended to perform and to which I cannot, for now, refer, because, as I told him: ‘This must remain between us, Mr. Notary, under client confidentiality, until such time as I deem otherwise. Are we understood?’

Completely understood. Though the good notary advised me that for him to carry out this request he would require various documents, the acquisition of which would oblige me to visit Bottomline at the bank.

![]()

‘The larva of a fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga / ver du Cayor)’

coloured drawing by A.J.E. Terzi, ca.1919℅ the Wellcome Collection.

And so the heist had hit a hitch, in the short term at least. I didn’t know where the papers were. At the bank even the lowliest of Bottomline and Sly’s subalterns had more standing than I did. If I dropped in, invited by management, the workers wouldn't so much as look up from their ledgers—and if someone did notice me it was to communicate, with excruciating clarity, the fact that I did not count.

And yet there they were, all laboring away with such alacrity on my behalf; reinforcing, through their assiduous devotion, the town's low opinion of me as a usurer. And it never would’ve occurred to any of these employees that, instead of heaping grateful praise upon them for their zeal, I might take offence.

Now, as I walked in, I saw that the clerks were gathered in the large back room, and were breaking into peals of laughter as they watched an argument between Stefano Sly and this guy called Rolypoly, a punchline for everyone in town, owing to his ridiculous wardrobe.

Rolypoly, being exceedingly short, was convinced that wearing a long jacket would’ve made him look even shorter. A fair assessment as far as it went. But one in which he'd utterly failed to consider, all puffed up and self-serious, with his flamboyant brigadier’s mustache, how ridiculous he might appear from behind, with this tiny jacket putting his bountiful buttocks on flagrant display.

Here he was in tears, dejected, sniffling, lashed by the laughter of the clerks and shaking an arm at Sly as he carefully enunciated:

‘For the love of God how you twist words!’

Sly was shouting in his face and shaking him furiously:

‘You vouched for that guy? You vouched for that guy? A worthless person who looks just like you!’

It would appear that this whole uproar was about somebody who’d applied for a loan on the recommendation of said Rolypoly, who'd vouched for his honorableness—and when I’d put this together I was seized by a fit of rebellion.

Suddenly abandoning the self-absorption of my spiritual crisis I pushed through two or three clerks and shocked all the assembled by bellowing at Sly:

‘What about you?! What do you know?! What gives you any right to judge someone else?!’

Sly spun around, dumbfounded to find me standing there, and stammered:

‘Wha-a—are you out of your mind?!’

Enabling me to blow all their minds by hurling an insult in his face:

‘Just like that wife you ought to keep locked up in the madhouse!’

He went white and started trembling:

‘What’d you just say?! I should what!?’

I gave a shrug, annoyed at the chaos my sudden arrival had created, but still utterly unruffled, and cut him short with a curt reply:

‘Yeah, obviously, as you know better than anyone.’

Sly fled in fury, hissing something between his clenched teeth. Then Bottomline appeared and ushered me into some little side office, and I smiled—so he'd know that violence was unnecessary, that everything was fine; and while on the one hand my satisfaction was genuinely reflected in that smile, on the other I was so irritated by his posture of rectitude and moral outrage that I could have murdered him. I started pacing around the little office, mildly surprised how the mood that had both possessed me and elicited my strange display wasn’t interfering with a lucid and precise inventory of the room’s contents, and pointedly interrupting the fiery denunciation Bottomline was leveling at me with a series of hapless, infantile questions about this or that object, amusing myself so much in the process that I only just kept myself from laughing.

Let me stress that I was doing all this with the mind of an inner stranger, someone who all of a sudden had become oddly cold and detached, not so much as a defense (though coldness serves such purposes well) but to erect a facade behind which it was easy for me to hide the terrifying reality I'd apprehended, the universality of which was growing ever more clear:

Of course! I thought. Everyone tries to force the world they have inside themselves on others, trying to externalise it, so that everyone has to see it solely in their way, and no one else exists except as seen through the lens of one singular and overpowering point of view. It's oppression.

Gazing at the clerks’ slack-jawed faces I thought:

It’s so clear! It’s so clear! What's the only kind of life any of us can hope to build? Miserly, fickle, uncertain. While the world's demagogues know just how to manipulate it! Or delude themselves into believing that they're able to manipulate it, making everyone bow and submit to their egos, until we all see, hear, think and talk the same way—like them.

I jumped up from where I was sitting, went to the window, and, with fresh resolve, faced Bottomline, cutting him off midsentence, forcing him to stand there agog as I pursued the ideas that consumed me:

‘Come on! Seriously! They're deluding themselves!’

‘Who's deluding themselves?’

‘The people that seek to oppress us, for instance! They’re fooling themselves because the truth, my friend, is they lack the power to oppress with anything more than words. Words that everyone understands and repeats in their own way. Everyone’s so-called world views are 100% formed like this. Do you see what I’m saying? And woe to whosoever finds himself branded with whatever word everybody repeats. Like: ‘usurer!’ Like: ‘crazy!’ So tell me: how can you quietly go about your business while someone is bent on persuading others that the you you are is the you he sees, and to fix you in everyone’s consciousnesses in accordance with his judgments, preventing others from seeing you and judging you for themselves?’

But I barely had time to register Bottomline’s bafflement when Sly was back. From the look in his eyes it was obvious how, in an instant, he had become my nemesis. And so I had found an enemy; an enemy borne of a misunderstanding; because, while what I'd said had been harsh, my words came from impulses that had nothing in particular to do with him—and I was ready to apologise. But instead, like a drunk, I upped the ante. As he launched himself at me, primed for battle, hollering, ‘I demand an explanation for what you said about my wife!’ I fell to my knees.

‘Of course!’ I shouted at him. ‘Look! Here!’

And I proceeded to bash my forehead against the floor.

Following which, repulsed by my own behavior (or, more accurately, by the idea that he and Bottomline might believe that I had knelt for him), I looked him in the eye, laughed, and immediately proceeded to bash my head on the floor two more times, thwack thwack.

‘Listen up—because you should be doing this, not me; understand? You’ve got to do this! And so does he, and so do we all—it’s our duty to lay ourselves at the feet of the so-called lunatics, just like this!’

I leapt to my feet, vibrating, as they exchanged frightened glances, as if to ask:

‘What the hell is he saying?"

‘New words!" I shouted. ‘Are you listening? Now go, go, go to wherever they keep the crazies locked up and listen to what they have to say! It's obvious that we only keep them there for our own convenience!"

Seizing Sly by the jacket lapels I shook him and screamed:

‘Do you get it, Stefano!? You're hardly my only target! You're all hot and bothered. But come on, my dear man, do you even have the faintest idea what your wife says about you? That you're a libertine, a thief, a forger, an imposter, and never do anything but tell lies! Infamous things. Even if nobody would ever believe them. But before you lock her up, let's all go and get a scandalous earful. I'd sure like to know the truth!’

Sly, lowering his eyes, turned to Bottomline, as if seeking counsel, and with exaggerated self-pity said:

‘Oh wonderful! And no one will ever believe it!’

‘Silence, coward!’ I shouted at him. ‘Look me in the eye!’

‘Now what do you want?’

‘Look me right in the eye!’ I repeated. ‘Relax. I won’t go spreading it around!’

He forced himself to look at me, miserably.

‘See!?’ I shouted. ‘See!? If only you could see yourself! The fear in your eyes!’

At his wit’s end he bellowed in my face, ‘Why are you acting crazy with me!?’

And I began to laugh, for a long, long time, unable to stop, watching the worry and confusion that this laughter engendered in them both. Until all at once I stopped, alarmed by the looks in their eyes. Even though I'd put them there. Controlling myself I affected a brusque tone and stated:

‘Now to the matter at hand. I'm here to inquire about a certain Marco Godson. How has this individual lived, for years, rent free, without the slightest action being taken to evict him.’

I wasn’t quite prepared for the way this question would plunge them into even greater confusion. They each looked at each other like they were searching for a witness to confirm or explain the supposition that I'd been possessed by an alien being.

‘But what do you mean? What's the point of all this?’ Bottomline asked.

‘You’re not following me? Marco. Godson. Does he, or does he not, pay rent?’

And they stared at each other, mouths agape. Which briefly made me break out laughing again; though I quickly mastered myself and said, as if I were addressing a naif who'd suddenly popped up in front of us:

‘Shouldn’t you be concerned with such things?’

With confusion tipping into fear, they looked me up and down as if seeking the source of a line they themselves were on the verge of uttering, but that had somehow come from me. Huh! Did I say that?

‘Well,’ he answered, seriously. ‘It’s no secret that your father let Marco Godson stay there for umpteen years without evicting him. Why are you asking about it now?’

I put a hand on Bottomline’s shoulder, and, adopting a different, though equally serious attitude, one weighed down with the weariness of long suffering, said:

‘Let this serve as your notice, my dear fellow, that I am not my father.’

Before sunset, in the alley outside Marco Godson’s hovel, it was already dark, and I can still see the unlit streetlight and hear water falling in a roar from a gutter; I can still see gawkers, come to witness an eviction, standing along the walls, protecting themselves from the rain, their numbers bolstered by pedestrians who’d paused out of curiosity, huddled under umbrellas, arrested by a crowd and a pile of pathetic possessions, thrown out and exposed to the elements, and the screams of Lady Diamond who, from time to time, in dishabille, came to a window and let loose some strange oaths, provoking whistles and coarse noises from the barefoot brats dancing around that heap of misery—rain be damned—and splashing water onto the first row of spectators, who cursed at them.

I caught snatches of conversation:

‘Worse than the father!’

‘Lord, in a downpour! He couldn't even hold off till tomorrow!’

‘To wreak such ruin on a poor madman!’

‘Bloodsucker! Bloodsucker!’

And here I was, in the flesh, escorted by a city commissioner and two guards, come specifically to oversee the eviction in person.

‘Bloodsucker! Bloodsucker!’

I smiled. Wanly, perhaps. But I was full-up with a voluptuous sensation that held my bowels suspended, tickled my uvula, and made it hard to swallow. Now and then, obliged to rest my eyes somewhere, I gazed raptly at the lintel atop the shack's door, taking a little refuge in the sight, sure it wouldn't occur to anyone else, at a moment like this, to happily take note of its melancholy aspect, its indifference to all the ruckus on the sidewalk, its peeling gray plaster, pitted in places, inanimate and indifferent to the embarrassment I felt upon noticing an old bedpan tossed out with the shack's other objects and immodesty displayed atop a nightstand in the middle of the alley, for all the world to see. But this rapturous daydreaming nearly cost me my head. When the eviction was complete, Marco Godson, emerging from the hovel with Diamond and spying me there in the alley—gazing abstractedly at that lintel, flanked by the commissioner and the two guards—hurled a hammer at me. It surely would have struck me in the temple had the commissioner not managed to yank me out of the way. Amidst shouts and confusion the two guards rushed to arrest this wretch who'd been so provoked at the sight of me; but the swelling crowd protected him and was about to turn against me, until a short black man, haggard but fierce-looking, one of Stampa the notary's clerks, clambered atop a table amid the pile of furnishings that filled the alley—almost leaped—and, accompanied by wild gesticulations, commenced calling out:

‘Stop! Stop! Listen! I work for Stampa the notary! Listen! Marco Godson! Where's Marco Godson? I’m here on behalf of Stampa the notary to inform you that there is a bequest for you! This usurer, Maggot.’

I was, how to say it, ecstatically anticipating a miracle: my transformation, from one instant to the next, in the eyes of the world. But suddenly, at the mention of my name, I felt as though my ecstasy had been shredded into a thousand pieces and my whole being thrown and scattered here and there by an explosion of the most piercing whistles, rowdy screams, and insults from the crowd, which was unable to comprehend, after the ferocious cruelty of the forced eviction, that I had made this bequest.

‘Death! Down with him!’ shouted the crowd.

‘Bloodsucker! Bloodsucker!’

Instinctively I raised my arms to show that they should wait—but, realizing this was a supplicant’s gesture, I lowered them straightaway, while the clerk atop the table waved his arms for silence and continued to shout:

‘No! No! Listen! He’s the benefactor! I have it on the authority of Stampa the notary—he did it! The bequest comes from him! The gift of a house for Marco Godson!’

And the whole crowd was shocked into silence. But I was far away by then, disheartened and disillusioned. Then—much as a flaming match, upon first touching a dry bundle of wood, can't be seen or heard at all, until a pop, a snap, a spark springs up, and all at once the whole bundle collapses, consumed by flames and smoke—the silence erupted into questions:

‘Him?’

‘A house?’

‘What?’

‘What house?’

‘Quiet!’

‘What's it mean?’

These were among the many sounds that erupted from the crowd and rapidly spread across it in an ever louder and more confused hubbub, while the young clerk confirmed:

‘Yes, yes—a house! His house, at #15 Saint Street. And that's not all! An additional contribution of ten thousand lire for the express purpose of building and outfitting a laboratory!’

Having cut myself off from the spectacle, anxious, at that moment, to flee, I didn't see what happened next. Only later did I learn of the enjoyment I might have experienced had I stayed.

I went and hid in the vestibule of the house on Saint Street, in a corner where the light from the stairwell could barely reach me, and lay in wait for Marco Godson to arrive and take ownership. Soon, pursued by the throng, employing a key the clerk had given him to open the front door, he found me leaning against the wall like a ghost, and for a moment he jumped back; then he gave me a wild-eyed look I will never forget, and, with a bestial howl, equal parts laughter and tears, he leaped forward and flung me against the wall, to either beatify or beat me, as he shouted wildly:

‘You’re crazy! You’re crazy! You're crazy!’

A cry that was taken up by the entire crowd outside the door:

‘Cra-zy! Cra-zy! Cra-zy!’

All because I wanted to show the world I might be something more than the man they imagined me to be.

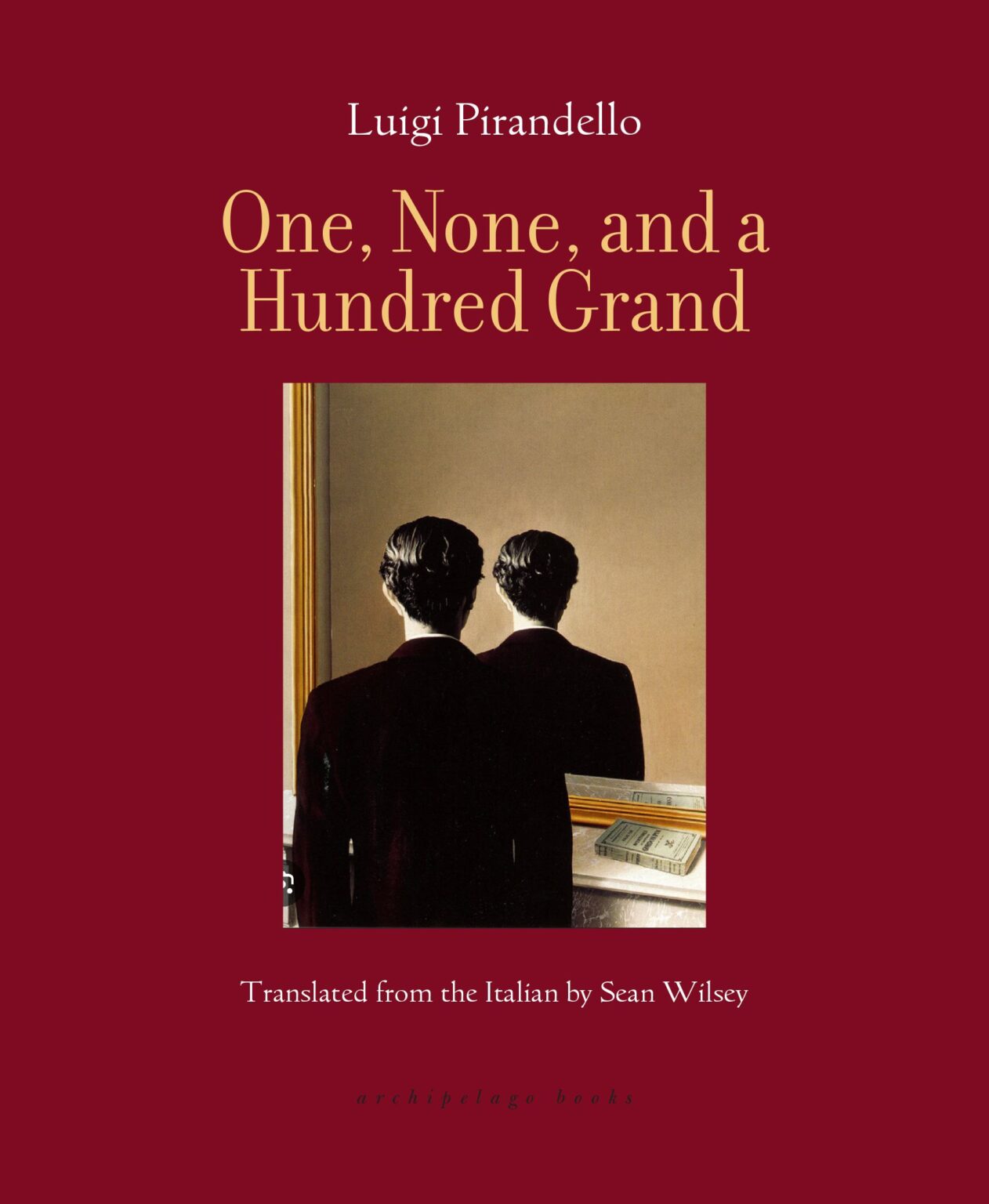

Published 21.01.25, order Wilsey’s translation of

Pirandello’s One, None, and a Hundred Grand

direct from the publisher Archipelago Books.

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) was a prolific Italian writer most famous for his plays, which inspired the théâtre del’absurde movement. An influence on writers and thinkers from Samuel Beckett to Jean-Paul Sartre, Pirandello won the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature for his contributions to European modernism. His metatheatrical play Six Characters in Search of an Author remains a cultural touchstone for contemporary playwrights.

Sean Wilsey is the author of a memoir, Oh the Glory of It All (Penguin, 2005), an essay collection, More Curious (McSweeney’s, 2014), and—in collaboration with the actress Molly Shannon—the bestselling memoir Hello, Molly! (Ecco, 2022). Wilsey’s documentary film about 9/11, IX XI, is forthcoming in 2026.