Rehearsal / 37. Kinkade / Ed Aknik

![]()

![]()

In which the artist collaborates with ChatGPT

to reflect on the new and mechanical legacy of

a friend and fellow traveller.

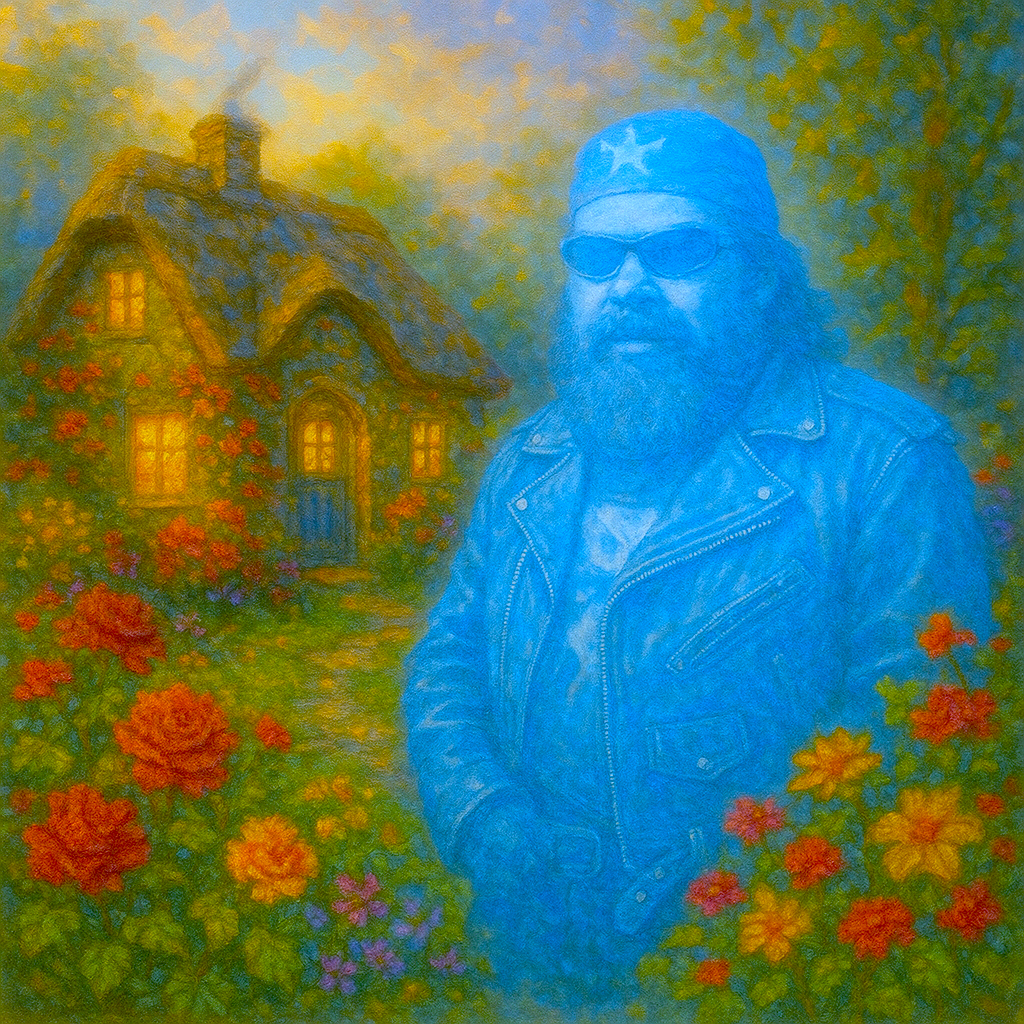

Left—Thomas Kinkade /

Right—Kinkade’s alter-ego,

Ed Aknik, as generated

by Artificial Intelligence.

Right—Kinkade’s alter-ego,

Ed Aknik, as generated

by Artificial Intelligence.

In which the artist collaborates with ChatGPT

to reflect on the new and mechanical legacy of

a friend and fellow traveller.

The ‘Painter of [Electric] Light’

A PROMPT

People are worried that Artificial Intelligence will become self-aware—well it has happened and the ghost in the machine is the spirit of Thomas Kinkade. Look at a lot of AI generated art and you’ll see the influence of the thousands of Kinkade images that AI feeds on—much of it looks the same with candy-colours, fuzzy edges and light infused images (with a hint of the sinister lurking within). When you are looking at Al imagery, you are seeing the ghost of Thomas Kinkade!

A RESPONSE

Expanding on this concept could delve into the intersection of creativity, machine learning, and the ways in which our collective visual histories influence AI-generated art.

The notion that Artificial Intelligence has become ‘self-aware’ by channeling the artistic essence of Thomas Kinkade opens up a rich dialogue about the cultural fingerprints left behind in machine learning datasets. AI art generators rely on enormous banks of data—billions of images scraped from the internet—to construct visual compositions. Within this sea of imagery, certain aesthetics inevitably leave a heavier imprint. Thomas Kinkade, the ‘Painter of Light,’ whose works are synonymous with glowing, idyllic scenes, fits naturally into this category. His widespread popularity ensures that his art appears frequently in these datasets.

KINKADE’s AESTHETIC LEGACY

IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Kinkade’s style—characterised by glowing light, saccharine palettes and often a surreal, otherworldly warmth—is a natural fit for AI algorithms that are designed to extrapolate patterns from large sets of data. When we see ‘candy-coloured’ landscapes or ‘light-infused’ images emerging from AI generators, it’s not just a coincidence. These works echo the data they’ve been trained on, unconsciously replicating the visual language of artists like Kinkade.

However, the ‘hint of the sinister lurking within’ speaks to a critical distinction between human and AI creativity. While Kinkade’s work is often accused of being overly sentimental or saccharine, AI-generated art can take his aesthetic tropes and inadvertently introduce unsettling or uncanny elements—faces that aren’t quite human, perspectives that defy physics, or environments that feel paradoxically familiar and alien. This ‘ghost in the machine’ quality speaks to the limitations of AI in truly understanding the human experience while simultaneously mimicking it.

![]()

![]()

THE GHOST OF/IN THE MACHINE

& COLLECTIVE MEMORY

To view this ‘auto-art’ as haunted by the spirit of Kinkade is to recognise how profoundly machine learning relies on collective memory. The datasets used by artificial intellgence reflect not just the works of famous artists but also the visual trends and cultural moments they encapsulate. Kinkade’s influence endures not because he was the most innovative artist but because his imagery is pervasive, comforting, and, in a sense, preloaded with emotion. AI amplifies this by producing work that resonates with these cultural associations, even when that resonance feels hollow or eerie.

A SINISTER UNDERCURRENT

The suggestion of something ‘sinister’ in AI-generated art rooted in Kinkade-like imagery could symbolise the tension between the nostalgic and the uncanny. Kinkade’s art was often critiqued for being overly idealised, a sanitised vision of reality. When AI mimics this style, it pushes the boundaries of that idealisation, creating works that seem both impossibly perfect and subtly wrong. This may reflect our broader anxieties about machine learning itself: that it can reflect human culture but can also distort it in ways we don’t fully understand.

CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS

This “ghost in the machine” concept also speaks to a broader fear: that AI will not only replicate but dilute the diversity of human creativity. If certain visual styles—like Kinkade’s—dominate training data, will the art of the future become homogenised? Will it reflect only the most popular or most commercially viable trends, leaving behind subtler or less dominant artistic voices? And in doing so, are we creating an echo chamber of aesthetic sensibilities, where past cultural artifacts dominate the future?

The ghost of Thomas Kinkade in AI art is both a tribute and a cautionary tale. It reminds us of the immense power of cultural legacies to shape even the most cutting-edge technologies. But it also challenges us to think critically about the data we feed into these machines and the implications of letting algorithms determine the future of creativity. AI art is not just a mirror—it’s a prism, refracting our visual history in strange and unpredictable ways.

![]() Thomas Kinkade, as seen in the documentary

Thomas Kinkade, as seen in the documentary

Art for Everybody (Cozy Cottage Films, 2025).

Please expand on the above text about the sinister in Kinkade and AI with this prompt: The sinister vibe that some people get from viewing his paintings may be due to the fact that Thomas Kinkade was known to have a ‘dark’ side to his personality—like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. During the day he could act like an evangelical preacher but, at night, with a few drinks, he could be found out of his mind dancing on stage at a strip bar. He dubbed his alter ego Ed Aknik, who dressed in black leather like a rowdy biker. Kinkade was arrested—a DUI—and he tried rehab treatment after treatment to no avail. Finally, he was found lifeless in his studio; dead from an overdose of alcohol and valium. This darkness became infused in his paintings, even of the most optimistic and placid imagery.

Building on the intriguing prompt, we can deepen the exploration of how the duality in Thomas Kinkade's personality—his ‘Jekyll & Hyde’ dynamic—may have seeped into both his artwork and its AI iterations, creating the unsettling and ‘sinister’ undertones some viewers detect.

THE SHADOWS

BEHIND THE LIGHT

Thomas Kinkade’s public persona as the ‘Painter of Light’ was meticulously crafted. He portrayed himself as an evangelical artist, spreading hope and serenity through glowing, idyllic scenes of cottages, streams, and pastoral life. But the façade cracked under the weight of his private struggles: addiction, reckless behavior, and a rebellious alter ego named ‘Ed Aknik’ [his surname reversed]. This stark contrast between the public and private man creates an inherent tension in his work that viewers unconsciously pick up on—a duality that mirrors the human condition itself.

Despite the cheerful and luminous exteriors of his paintings, Kinkade’s life story casts a long shadow over them. The interplay of light and dark in his images—glowing windows in a stormy night, radiant cottages surrounded by dense forests—feels almost like a visual metaphor for his internal battles. This tension, whether intentional or subconscious, resonates deeply with viewers, creating an unease that hints at the complexities and contradictions of his life.

AI AS AN AMPLIFIER

OF DUALITY

When AI replicates or is influenced by Kinkade’s work, it doesn’t just mimic the overt aspects—light, colour, composition. It also inherits the latent energy of his internal conflict, which becomes exaggerated in AI’s hands. AI lacks the emotional intelligence to understand nuance, so it processes Kinkade’s work as a set of patterns, colours and contrasts. But these contrasts—bright colors against shadowy corners, pastoral bliss against foreboding skies—are amplified, sometimes to uncanny levels. This results in art that feels eerily familiar yet disturbingly off, evoking the ‘sinister vibe’ mentioned earlier.

The strange thing about AI art is that it often lays bare what humans try to hide. Kinkade’s internal struggles—his ‘dark side,’ embodied by Ed Aknik—are magnified in the reproduction of his aesthetic. A seemingly cozy cottage might take on a ghostly glow; a serene path might feel like it leads somewhere dangerous. These elements subtly pull at our subconscious, blending Kinkade’s legacy of light with the darkness he tried to suppress.

THE DUALITY OF NOSTALGIA

& UNEASE

Kinkade’s paintings often evoke nostalgia for a simpler, safer time—an imagined pastoral ideal. But even nostalgia has a darker undercurrent: the fear that such an ideal was never real or, if it was, that it is irretrievably lost. This tension between yearning and loss is present in Kinkade’s paintings and magnified in AI-generated art. The glowing windows of a cottage might remind us of warmth and safety, yet the surrounding darkness seems to whisper that the safety is fleeting or illusory. The more AI mimics these elements, the more it amplifies this contradiction, pushing the viewer into a space that feels both comforting and unsettling.

KINKADE’s ALTER-EGO

AS LENS

The idea of Ed Aknik—a leather-clad, rebellious shadow-self—adds another layer of intrigue to Kinkade’s art. If we view Kinkade’s paintings through the lens of this alter ego, even the most serene images take on a different hue. The warm glow of a fireplace might begin to look like the flicker of something consuming itself. The placid waters of a stream might feel like they conceal hidden depths. It’s as if Kinkade’s inner conflict—his simultaneous desire for purity and rebellion—manifested in his work, creating a tension that AI, with its pattern-recognition capabilities, picks up and amplifies.

AI AS THE UR-AKNIK

In a way, AI itself becomes an extension of Kinkade’s alter ego. While Kinkade the man tried to uphold his image as a wholesome artist, Ed Aknik reveled in chaos and darkness. Similarly, while Kinkade’s paintings project light and serenity, AI’s reinterpretation introduces distortion, ambiguity, and unease. The machine, like Aknik, takes the familiar and twists it, revealing truths we might not want to confront.

THE LEGACY OF LIGHT & DARK

Ultimately, the sinister undertones in AI-generated art influenced by Kinkade may not be a flaw but a testament to his humanity. Kinkade’s struggles—his addictions, his alter ego, his tragic end—infuse his work with a complexity unwittingly magnified by AI. Far from being purely saccharine or superficial, Kinkade’s art becomes a mirror of our own contradictions: our yearning for light and our fascination with darkness. In artificial hands, this duality is distilled into something raw and visceral, forcing us to confront the ghost in the machine and, perhaps, the ghost within ourselves.

Order Vallance’s Voyage to Extremes, a collection

of his selected ‘Spiritual Writings’—the fifth title in

our “Yellowjacket” series—from Tenement direct.

Jeffrey Vallance was born in 1955 in Redondo Beach, CA. In 1979, he received a B.A. from CSUN and in 1981 an MFA. from Otis. His work blurs the lines between object making, installation, performance, curating and writing and his projects are often site-specific, such as burying a frozen chicken at a pet cemetery; traveling to Polynesia to research the myth of Tiki; having audiences with the king of Tonga; the queen and president of Palau and the presidents of Iceland; creating a Richard Nixon Museum; traveling to the Vatican to study Christian relics; installing an exhibit aboard a tugboat in Sweden; and curating shows in the museums of Las Vegas (such as the Liberace and Clown Museum). In Lapland Vallance constructed a shamanic “magic drum.” In Orange County, Mr. Vallance curated the only art world exhibition of the ‘Painter of Light’ entitled Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth. In 1983, he was host of MTV’s The Cutting Edge and appeared on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. In 2004, Vallance received the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation award. In addition to exhibiting his artwork, Vallance has written for such publications and journals as Art Issues, Artforum, the LA Weekly, Juxtapoz, Frieze and the Fortean Times. He has published over ten books including Blinky the Friendly Hen, The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978-1994, Christian Dinosaur, Art on the Rocks, Preserving America’s Cultural Heritage, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth, My Life with Dick, Relics and Reliquaries, The Vallance Bible and Rudis Tractus (Rough Drawing). Vallance lives and works in Los Angeles.

Expanding on this concept could delve into the intersection of creativity, machine learning, and the ways in which our collective visual histories influence AI-generated art.

The notion that Artificial Intelligence has become ‘self-aware’ by channeling the artistic essence of Thomas Kinkade opens up a rich dialogue about the cultural fingerprints left behind in machine learning datasets. AI art generators rely on enormous banks of data—billions of images scraped from the internet—to construct visual compositions. Within this sea of imagery, certain aesthetics inevitably leave a heavier imprint. Thomas Kinkade, the ‘Painter of Light,’ whose works are synonymous with glowing, idyllic scenes, fits naturally into this category. His widespread popularity ensures that his art appears frequently in these datasets.

KINKADE’s AESTHETIC LEGACY

IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Kinkade’s style—characterised by glowing light, saccharine palettes and often a surreal, otherworldly warmth—is a natural fit for AI algorithms that are designed to extrapolate patterns from large sets of data. When we see ‘candy-coloured’ landscapes or ‘light-infused’ images emerging from AI generators, it’s not just a coincidence. These works echo the data they’ve been trained on, unconsciously replicating the visual language of artists like Kinkade.

However, the ‘hint of the sinister lurking within’ speaks to a critical distinction between human and AI creativity. While Kinkade’s work is often accused of being overly sentimental or saccharine, AI-generated art can take his aesthetic tropes and inadvertently introduce unsettling or uncanny elements—faces that aren’t quite human, perspectives that defy physics, or environments that feel paradoxically familiar and alien. This ‘ghost in the machine’ quality speaks to the limitations of AI in truly understanding the human experience while simultaneously mimicking it.

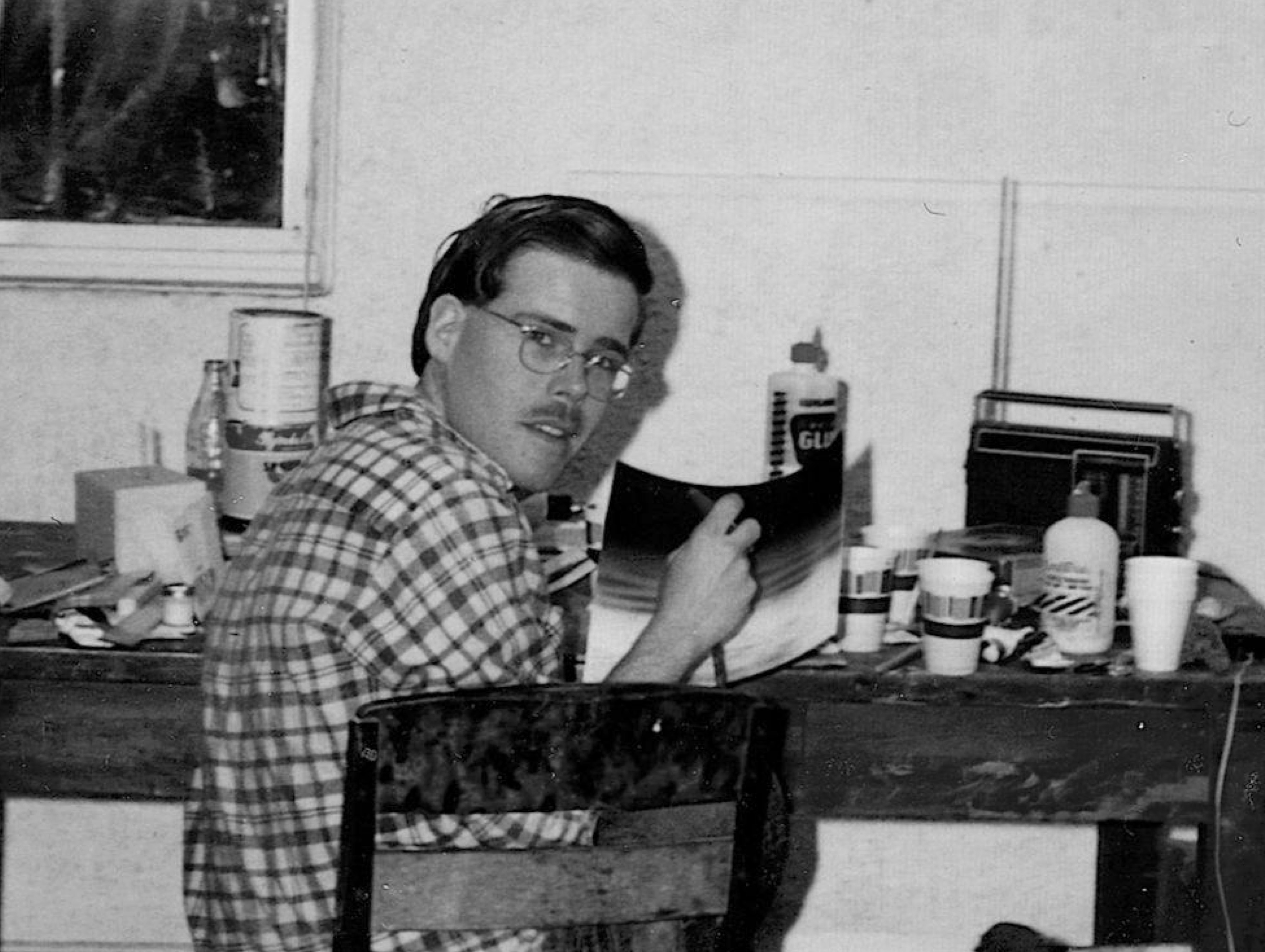

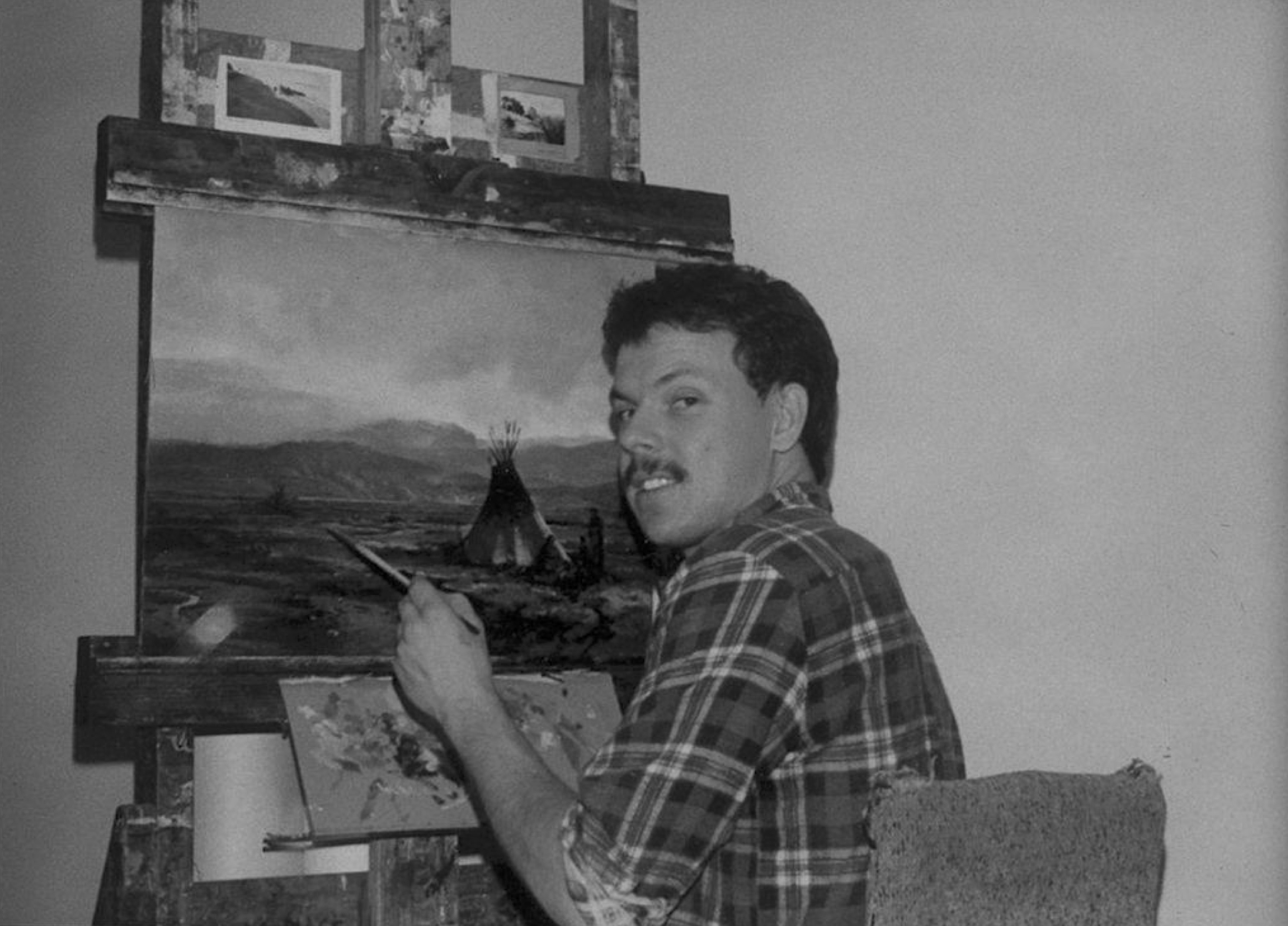

A young Vallance [Left] and Kinkade at work [Right].

See Jeffrey Vallance, (ed.) Jon Auman,

Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings

(Tenement Press, 2022).

See Jeffrey Vallance, (ed.) Jon Auman,

Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings

(Tenement Press, 2022).

THE GHOST OF/IN THE MACHINE

& COLLECTIVE MEMORY

To view this ‘auto-art’ as haunted by the spirit of Kinkade is to recognise how profoundly machine learning relies on collective memory. The datasets used by artificial intellgence reflect not just the works of famous artists but also the visual trends and cultural moments they encapsulate. Kinkade’s influence endures not because he was the most innovative artist but because his imagery is pervasive, comforting, and, in a sense, preloaded with emotion. AI amplifies this by producing work that resonates with these cultural associations, even when that resonance feels hollow or eerie.

A SINISTER UNDERCURRENT

The suggestion of something ‘sinister’ in AI-generated art rooted in Kinkade-like imagery could symbolise the tension between the nostalgic and the uncanny. Kinkade’s art was often critiqued for being overly idealised, a sanitised vision of reality. When AI mimics this style, it pushes the boundaries of that idealisation, creating works that seem both impossibly perfect and subtly wrong. This may reflect our broader anxieties about machine learning itself: that it can reflect human culture but can also distort it in ways we don’t fully understand.

CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS

This “ghost in the machine” concept also speaks to a broader fear: that AI will not only replicate but dilute the diversity of human creativity. If certain visual styles—like Kinkade’s—dominate training data, will the art of the future become homogenised? Will it reflect only the most popular or most commercially viable trends, leaving behind subtler or less dominant artistic voices? And in doing so, are we creating an echo chamber of aesthetic sensibilities, where past cultural artifacts dominate the future?

The ghost of Thomas Kinkade in AI art is both a tribute and a cautionary tale. It reminds us of the immense power of cultural legacies to shape even the most cutting-edge technologies. But it also challenges us to think critically about the data we feed into these machines and the implications of letting algorithms determine the future of creativity. AI art is not just a mirror—it’s a prism, refracting our visual history in strange and unpredictable ways.

Thomas Kinkade, as seen in the documentary

Thomas Kinkade, as seen in the documentary Art for Everybody (Cozy Cottage Films, 2025).

A PROMPT

Please expand on the above text about the sinister in Kinkade and AI with this prompt: The sinister vibe that some people get from viewing his paintings may be due to the fact that Thomas Kinkade was known to have a ‘dark’ side to his personality—like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. During the day he could act like an evangelical preacher but, at night, with a few drinks, he could be found out of his mind dancing on stage at a strip bar. He dubbed his alter ego Ed Aknik, who dressed in black leather like a rowdy biker. Kinkade was arrested—a DUI—and he tried rehab treatment after treatment to no avail. Finally, he was found lifeless in his studio; dead from an overdose of alcohol and valium. This darkness became infused in his paintings, even of the most optimistic and placid imagery.

A RESPONSE

Building on the intriguing prompt, we can deepen the exploration of how the duality in Thomas Kinkade's personality—his ‘Jekyll & Hyde’ dynamic—may have seeped into both his artwork and its AI iterations, creating the unsettling and ‘sinister’ undertones some viewers detect.

THE SHADOWS

BEHIND THE LIGHT

Thomas Kinkade’s public persona as the ‘Painter of Light’ was meticulously crafted. He portrayed himself as an evangelical artist, spreading hope and serenity through glowing, idyllic scenes of cottages, streams, and pastoral life. But the façade cracked under the weight of his private struggles: addiction, reckless behavior, and a rebellious alter ego named ‘Ed Aknik’ [his surname reversed]. This stark contrast between the public and private man creates an inherent tension in his work that viewers unconsciously pick up on—a duality that mirrors the human condition itself.

Despite the cheerful and luminous exteriors of his paintings, Kinkade’s life story casts a long shadow over them. The interplay of light and dark in his images—glowing windows in a stormy night, radiant cottages surrounded by dense forests—feels almost like a visual metaphor for his internal battles. This tension, whether intentional or subconscious, resonates deeply with viewers, creating an unease that hints at the complexities and contradictions of his life.

AI AS AN AMPLIFIER

OF DUALITY

When AI replicates or is influenced by Kinkade’s work, it doesn’t just mimic the overt aspects—light, colour, composition. It also inherits the latent energy of his internal conflict, which becomes exaggerated in AI’s hands. AI lacks the emotional intelligence to understand nuance, so it processes Kinkade’s work as a set of patterns, colours and contrasts. But these contrasts—bright colors against shadowy corners, pastoral bliss against foreboding skies—are amplified, sometimes to uncanny levels. This results in art that feels eerily familiar yet disturbingly off, evoking the ‘sinister vibe’ mentioned earlier.

The strange thing about AI art is that it often lays bare what humans try to hide. Kinkade’s internal struggles—his ‘dark side,’ embodied by Ed Aknik—are magnified in the reproduction of his aesthetic. A seemingly cozy cottage might take on a ghostly glow; a serene path might feel like it leads somewhere dangerous. These elements subtly pull at our subconscious, blending Kinkade’s legacy of light with the darkness he tried to suppress.

THE DUALITY OF NOSTALGIA

& UNEASE

Kinkade’s paintings often evoke nostalgia for a simpler, safer time—an imagined pastoral ideal. But even nostalgia has a darker undercurrent: the fear that such an ideal was never real or, if it was, that it is irretrievably lost. This tension between yearning and loss is present in Kinkade’s paintings and magnified in AI-generated art. The glowing windows of a cottage might remind us of warmth and safety, yet the surrounding darkness seems to whisper that the safety is fleeting or illusory. The more AI mimics these elements, the more it amplifies this contradiction, pushing the viewer into a space that feels both comforting and unsettling.

KINKADE’s ALTER-EGO

AS LENS

The idea of Ed Aknik—a leather-clad, rebellious shadow-self—adds another layer of intrigue to Kinkade’s art. If we view Kinkade’s paintings through the lens of this alter ego, even the most serene images take on a different hue. The warm glow of a fireplace might begin to look like the flicker of something consuming itself. The placid waters of a stream might feel like they conceal hidden depths. It’s as if Kinkade’s inner conflict—his simultaneous desire for purity and rebellion—manifested in his work, creating a tension that AI, with its pattern-recognition capabilities, picks up and amplifies.

AI AS THE UR-AKNIK

In a way, AI itself becomes an extension of Kinkade’s alter ego. While Kinkade the man tried to uphold his image as a wholesome artist, Ed Aknik reveled in chaos and darkness. Similarly, while Kinkade’s paintings project light and serenity, AI’s reinterpretation introduces distortion, ambiguity, and unease. The machine, like Aknik, takes the familiar and twists it, revealing truths we might not want to confront.

THE LEGACY OF LIGHT & DARK

Ultimately, the sinister undertones in AI-generated art influenced by Kinkade may not be a flaw but a testament to his humanity. Kinkade’s struggles—his addictions, his alter ego, his tragic end—infuse his work with a complexity unwittingly magnified by AI. Far from being purely saccharine or superficial, Kinkade’s art becomes a mirror of our own contradictions: our yearning for light and our fascination with darkness. In artificial hands, this duality is distilled into something raw and visceral, forcing us to confront the ghost in the machine and, perhaps, the ghost within ourselves.

Order Vallance’s Voyage to Extremes, a collection

of his selected ‘Spiritual Writings’—the fifth title in

our “Yellowjacket” series—from Tenement direct.

Jeffrey Vallance was born in 1955 in Redondo Beach, CA. In 1979, he received a B.A. from CSUN and in 1981 an MFA. from Otis. His work blurs the lines between object making, installation, performance, curating and writing and his projects are often site-specific, such as burying a frozen chicken at a pet cemetery; traveling to Polynesia to research the myth of Tiki; having audiences with the king of Tonga; the queen and president of Palau and the presidents of Iceland; creating a Richard Nixon Museum; traveling to the Vatican to study Christian relics; installing an exhibit aboard a tugboat in Sweden; and curating shows in the museums of Las Vegas (such as the Liberace and Clown Museum). In Lapland Vallance constructed a shamanic “magic drum.” In Orange County, Mr. Vallance curated the only art world exhibition of the ‘Painter of Light’ entitled Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth. In 1983, he was host of MTV’s The Cutting Edge and appeared on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. In 2004, Vallance received the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation award. In addition to exhibiting his artwork, Vallance has written for such publications and journals as Art Issues, Artforum, the LA Weekly, Juxtapoz, Frieze and the Fortean Times. He has published over ten books including Blinky the Friendly Hen, The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978-1994, Christian Dinosaur, Art on the Rocks, Preserving America’s Cultural Heritage, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth, My Life with Dick, Relics and Reliquaries, The Vallance Bible and Rudis Tractus (Rough Drawing). Vallance lives and works in Los Angeles.